Thu July 10th Open 11 AM–5 PM

AFTER LIFE (we survive)

AFTER LIFE (we survive) is the second exhibition in a series that initially asked: how have artists of color, Indigenous, trans and queer artists used new media, performance, and visual art to imagine present and future possibilities for our communities that have been ravaged by ecological collapse and other forms of slow and spectacular violence?

In the two years since the first exhibition, AFTER LIFE (what remains), was shown at The Alice Gallery in Seattle, our collective reality has radically shifted. AFTER LIFE (we survive) opens at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts on November 9, just days after the 2020 presidential election, eight months since the beginning of the first quarantine restrictions were placed in San Francisco, and as wildfires continue to burn up and down the California coast as they have without cease since mid-August. Originally designed for presentation on YBCA’s second floor galleries, this exhibition has been quite literally turned inside out for public viewing outdoors and online; the demands on everyone involved with this transformation have been nothing short of extraordinary. It is a deep understatement to say that this is not a “normal” time to open an art exhibition—even one that speaks to our current social, political, and environmental circumstances.

In this moment of collective anger and militant mourning1 for the pasts that have been stolen from us, from a present that is actively trying to kill so many of us, dreading a future that is precarious at best and deathly at worst— the question underlying AFTER LIFE (we survive) has likewise transformed to become: what good is art at a time like this?

One answer might be found in assessing the long durée of violence and the organized resistance to it. The title for these exhibitions, AFTER LIFE, was first inspired by the writing of professor Saidiya Hartman, who wrote in 2007’s Lose Your Mother that to live in the present is to live in the afterlife of slavery, a space-time in which Black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and political arithmetic entrenched centuries ago. Markers of this afterlife, for Black folks, are “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment.”2 Hartman’s articulation of the ongoing afterlife of slavery prompted me, as a scholar of race and sexuality, to further consider the multiple and overlapping afterlives we inhabit within and outside of the United States.

“The question underlying AFTER LIFE (we survive) has likewise transformed to become: what good is art at a time like this?”

We live in the afterlife of US imperialism across oceans, colonialism’s ongoing effects impacting the daily lives of people in the Philippines, Guam, Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, and Cuba: people who are vulnerable to police violence, hurricanes, typhoons, earthquakes, and fires and are met with thrown paper towel rolls and a blind eye. We live in the afterlife of the United States’s militarized incursions into Mexico and Central America, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and North Africa, with its making of people into asylum seekers and refugees who have been ripped apart from their families at US borders and detained in secret facilities. Throughout the Americas, we live in the afterlife of European settler colonialism over the continents’ indigenous peoples: peoples that have survived genocide, boarding schools, and forced resettlement, and the ongoing destruction of sacred and tribal lands by nuclear testing, toxic dumping, and multiple forms of extractivism such as fracking, deforestation, and drilling. Prior to this exceptional moment of global pandemic, then, we must remember that for people of the global majority, we have been living in the afterlife, for a long time. So, too, have we been mobilizing publicly and clandestinely for the survival of ourselves and our kin, human and non-human alike. We organize for the long term for our generational survival, and don’t stop fighting for our lives when the media has lost interest in us.

Witnessing and imagining otherwise possibilities—or conjuring futures where water is clean and air is breathable, and where our Black, and Brown, and Indigenous, and Queer, and Trans lives matter—this is the urgent work that artists are called to do, right now and so long as we live in these afterlives of violence.3 Artists mine for unseen and unheard stories. Artists rework the past and reframe the present, contributing to the growing archives of how we survived through these times for others to learn from, and hopefully utilize, in the realization of their own freedom dreams.

What can viewing publics in the present and in the future learn from the archives of survival and resilience contained within AFTER LIFE (we survive)?

First: Indigenous, Black, Asian, and Latinx femmes and queer folks were, are, and will be at the center of multiracial and coalitional movements to restore humanity’s right relationship to the earth and to one another.

Black feminist writer and activist adrienne maree brown4 and Potawatami botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer,5 along with countless environmental justice activists and Indigenous land and water defenders, have called for humans to reorient themselves towards having a right relationship to the earth and its human and non-human inhabitants. Theirs is a vision beyond basic environmental awareness and simplistic campaigns to ban plastic straws or to begin recycling mandates. Seeking right relationship coincides with demands for sovereignty from coal mines and nuclear power plants, ceasing the dumping of trash and toxic substances, and remediation for the nuclear testing in the “wastelands” of the desert and evacuated Pacific islands.6 ¡Ya Basta!7 Enough is enough!

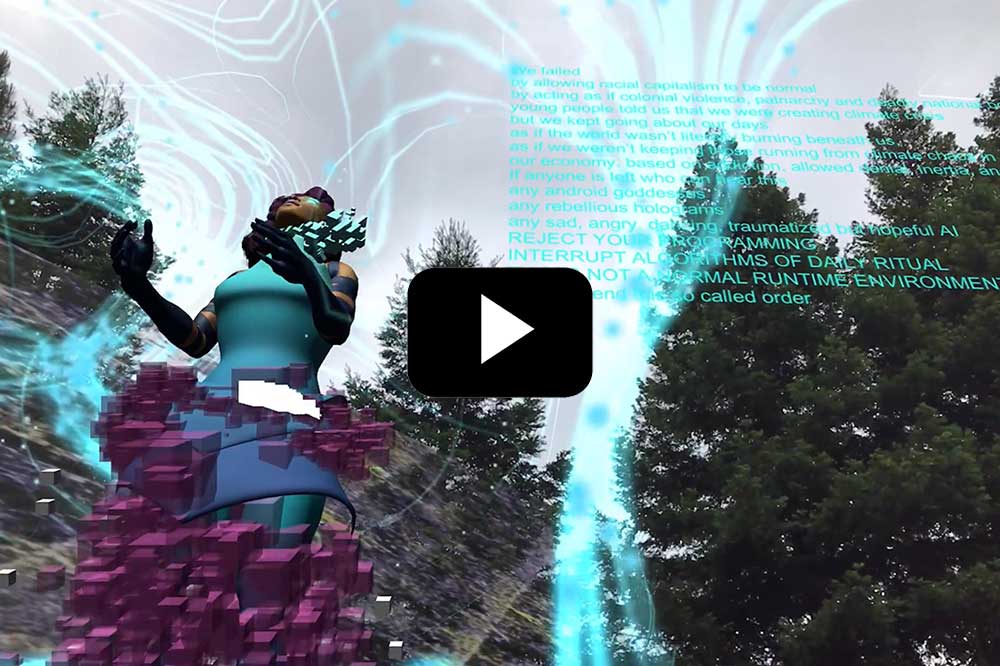

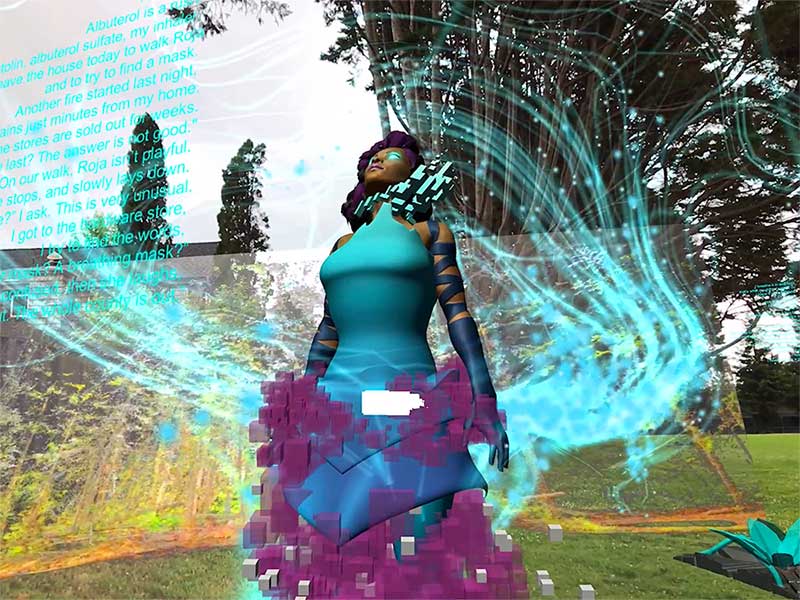

Getting into the mindset of right relationship requires acknowledgement and mourning of loss, which we see practiced by AFTER LIFE artists micha cárdenas, Courtney Desiree Morris, Rea Tajiri, and FIFTY-FIFTY. micha cárdenas’s immersive Augmented Reality video game Sin Sol / No Sun (2020) was first created in the aftermath of the 2017 wildfires in the Pacific Northwest, and was updated again as the artist fled wildfires this summer in the Santa Cruz mountains. Players interact with an avatar, Aura, who shares poetic meditations of escaping the past of 2020, from the contemporary world full of fire that she lives in 2070. Traveling alongside Aura and her dog Roja as she tries to find asthma medication and other supplies while fleeing the fires, players experience the realities of disabled, trans, Latinx and other communities of color whose life chances are shortened by natural and unnatural disasters. Aura is not alone, however, as she draws strength from the poetry of Black and Latinx feminists, whose words and activism over the decades have helped keep communities alive.

Courtney Desiree Morris’s photographs from the Solastalgia series (2019) allow us access to her “mourning diary” for the town of Mossville, Louisiana, where her family has lived for generations, as bearers of land titles granted after the 1862 Southern Homestead Act.8 With multinational oil companies taking up residence in the region, Morris’s photographs condemn their unwelcome role in destroying this rural place. Solastalgia, simultaneously, honors the legacy of Black women like her late grandmother, Mrs. Freeman, whose vital leadership and participation in cultural institutions such as the Baptist Church have sustained Black life in the South despite repeated attempts to destroy it.

Continuing the process of mourning and memorializing lost places and connections, Rea Tajiri’s 2014 film Lordville is an experimental documentary about a town in upstate New York slowly disappearing due to flooding and the aging and outmigration of its current, white settler inhabitants. The film uncovers buried histories of Lenape settlement in Lordville, an act we might interpret as an attempt at reparations between the filmmaker, a Japanese American woman descended from survivors of the WWII internment camps, and those indigenous to this place.

FIFTY-FIFTY invites the Bay Area and the global publics’ participation in Portable Memories in Rising Seas (2016–present), an ongoing project that captures peoples’ memories of shorelines being swallowed by sea level rise. The public is invited to witness the memories of others’ shifting relationship to land and oceans, before contributing their own image that adds to the expanding archive. In a moment of interspecies collaboration, fish are invited by the artists to become co-witnesses to these memories of the sea. While the drawings initially appear joyful with their bright colors and simple lines, and the artists’ interactions with the fish are charming, the project unsettles with its poignant documentation of real, irreplaceable losses of place in the absence of right relations.

“Prior to this exceptional moment of global pandemic, then, we must remember that for people of the global majority, we have been living in the afterlife, for a long time.”

Second: That we are the ones we have been waiting for.

Worldmaking is a collaborative endeavor. For Art 25: Art in the 25th Century and Super Futures Haunt Qollective, right relations are modeled through the collaborative process itself, as both groups are composed of Indigenous artists and artists of color whose desire-based practices envision the kinds of relationships they wish for all of us to cultivate.9 Their coming together is the work of art that they generate, not for their own ego-gratification, but for the collective project of getting free.

Super Futures Haunt Qollective (SFHQ) are a band of three future ghosts whose visitations on stolen land—from Kumeyaay to Modoc to Duwamish to Ohlone territories—activate Indigenous presence as a reminder that indigeneity refuses to die, be hidden, or simply vanish away. In Super Furs for the Super Futures (2020), their latest project commissioned for AFTER LIFE (we survive), SFHQ reanimates the specter of Geronimo the Beaver, who was repeatedly dropped out of airplanes, along with dozens of other beavers, in a “failed” attempt at wildlife relocation in the late 1940s through the early 1950s.10 The beavers were supposed to create dams in their new homes, but things didn’t always go according to human plans. SFHQ’s conjuring of Geronimo suggests that there is shared power in more-than-human kinships with animals who have learned how to wholly refuse colonial demands.

Art 25: Art in the 25th Century’s series Future Ancestors (2019) asserts the artists’ visual sovereignty over their own images11: the larger-than-life photographs and accompanying sound and text pieces are never for sale. Theirs is a performance of Black and Indigenous intimacy and togetherness that cannot be identified with or co-opted into any of the hierarchical forms of relationship which are most valued by our capitalist society: client-server, boss-worker, or husband-wife. It is also an offering of beauty, hope, and tenderness for a world that is so broken and frequently devoid of meaningful connection. Future Ancestors perhaps models best the principles underlying right relationship as a relationship of reciprocity, where giving and receiving are acts of collective survival and care. In the 21st century, we need to hold each other with mutual aid12 and revolutionary love, if we are to make it through to the 25th.

Third: future generations will learn from AFTER LIFE (we survive) that white allies labored to become accomplices towards racial justice and environmental renewal.

Joanna Macy, a white scholar of Buddhism and deep ecology, asks a deceptively simple question: how do we learn to listen to the earth and to one another? Learning to listen and to observe can help a person move away from the trap of paralysis (or shutting down in fear) and the trap of panic, social hysteria and turning on one another.13 “To overcome fear,” she says, “you have to look at what you’re afraid to see.”14 Macy’s decades-long eco-activism and Buddhist practice invites people of all backgrounds to feel collectively, not privately—to grieve the loss of connection, to be angry at humankind’s extractive relationship to earth and its creatures, to bemoan the futility of activism to making real change—in order to then do something rather than remain stuck in those feelings. Macy’s lessons are ones that white allies can and have learned from, in order to transform into real accomplices to communities of color.

Jeremiah Barber’s Lightroom/Darkroom is an exercise in re-imagining working relationships with plants and animals towards shared ends. Barber’s speculative proposals involve non-human partners in experiments to create working machines capable of recording images and sound—from pigeons to fungi to cats to photosensitive plants. His project mines the history of foundational photographic and cinematic studies, such as Muybridge’s studies of animal locomotion and Neubronner’s pigeon photography, while critiquing its racial and colonial underpinnings15. Lightroom/Darkroom begs the question: can anything be recuperated from its origins in white supremacy, or must it always be completely thrown out in order to create anew?

Taking eco-activism to the space-time of the 21st century, Coven Intelligence Program’s One two three potions a secret word / and soon you’ll see a freer world (2020) entices the public to join their revolutionary anti-capitalist alliance among witches, plants, and machines. Speculating what a truly collective uprising against domination could look like both on the ground and in the network, Coven Intelligence Program’s interactive SpellWeaver app elicits us to work for just and livable futures, using every possible tool.

Finally: our future selves will see that it was dreams of queer pasts, presents, and futures which sustained us in these afterlives. They will know that queer, Brown, Black, and Indigenous folks never stopped fighting to preserve our collective humanity in this quite broken world.

Like so many others in these precarious times—in these ongoing afterlives of violence that we all live in and which we’re unequally devastated by—the artists in AFTER LIFE (we survive) dream of a world without borders. A place where separated Mexican and Central American children have been safely reunited with their parents. A world where Filipinos, Palestinians, and other people from Southeast Asia and SASWANA (South Asia, Southwest Asia, North Africa) are no longer labeled as “terrorists” and prevented from free mobility and movement. Societies in which Indigenous ancestors hoarded in museums are rightfully returned to their people, and Indigenous sovereignty over land and resources is restored. We dream of these and more queer and femme futures grounded by our own spiritual practices, cultures, traditions, as another path for our contemporary world still entrapped in extractive systems, colonizing religions, and deathly norms.

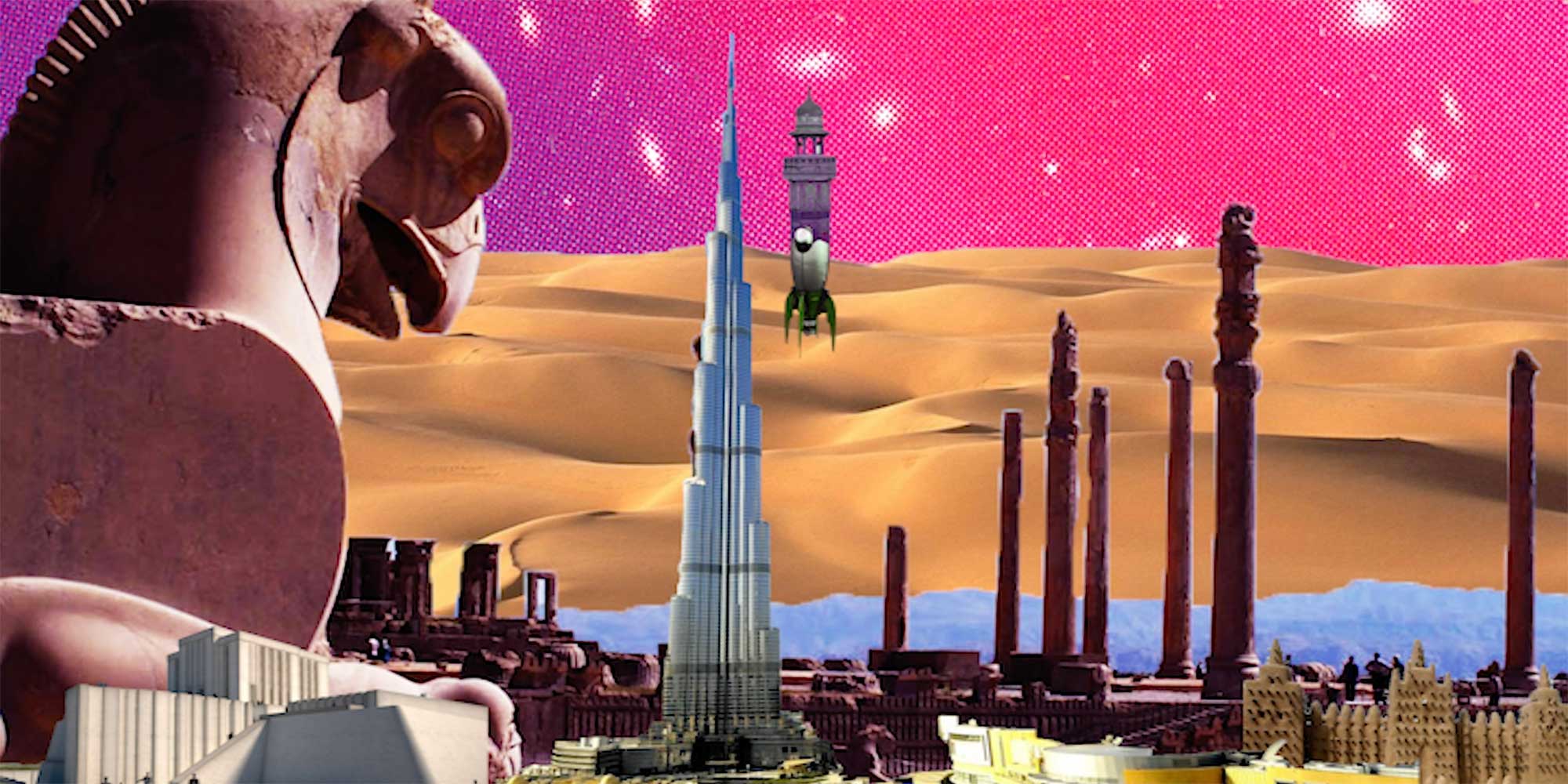

Queer dreams animate all of the projects in AFTER LIFE, yet are most apparent in the projects by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and alejandro t. acierto. Tomorrow We Inherit the Earth (2020), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s queer resurrection of Muslim revolutionary heroes, martyrs, stories and sacred sites, gloriously blasts off into spaces where more of us have a real chance at life. Grace and Mercy 556 (2020), two highly bedazzled minaret-rocket ships, take us to a brilliant world far from present-day San Francisco, a highly gentrified place that is unaffordable for most and where Black and Latinx communities are the most policed and have become most susceptible to COVID exposure and infection. Bhutto’s hypercolored visions of the future are a welcome respite from the bleakness of our present condition.

alejandro t. acierto’s How to take up space when you’ve only been given the margin (2019) calls forth LGBTQ ancestors Sylvia Rivera and ACT UP to light our path for the ongoing fight for queer and trans lives. “Y’all Better Listen,” Rivera’s fiery speech at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade is crowned by a three-dimensional neon pink triangle that blesses her, and all of us, even as it reminds us that SILENCE=DEATH.16 This installation illuminates the duration and endurance of QTPOC rebellion and liveliness, even in the darkest of times.

Together, the 17 artists and art collectives in AFTER LIFE (we survive) evidence a multiplicity of approaches to remembering past loss and continuing resistance through their crafting of alternative visions of the worlds that they hope to inhabit in this lifetime or the next. In the waning months of 2020 and at the beginning of a new year, may this archive of survivance17 serve as a source of inspiration and sustenance for the ongoing struggle to birth the afterwards (and not the afterlives) of these imperiled times.

Thea Quiray Tagle, Curator

November 1, 2020

- Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October Vol. 51 (Winter 1989): 3-18.

- Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007. p. 6.

- Always grateful to Ashon Crawley for his writing and creative practice in thinking through “otherwise possibilities” and “otherwise worlds.”

- “Yes. I always make the distinction between ‘right’ versus ‘right relationship.’ So not doing something that’s right for the entire planet in terms of how we’re supposed to be, but having the right kind of relationship to the planet. That is something we can feel our way into, and the most devastating thing on Earth right now is that there’s so many people who’ve been cut off from being able to feel that. That’s a big part of my life: How can I make you feel pleasure to remind you about the miracle? The miracle’s there. Enjoy it.”- adrienne maree brown in “On vulnerability, playfulness, and keeping yourself honest,” interview by Anupa Mistry, The Creative Independent, July 11, 2019.

- “In the indigenous worldview, a healthy landscape is understood to be whole and generous enough to be able to sustain its partners. It engages land not as a machine but as a community of respected non-human persons to whom we humans have a responsibility… Renewal of relationships includes water that you can swim in and not be afraid to touch. Restoring relationship means that when the eagles return, it will be safe for them to eat the fish…. Restoring land without restoring relationship is an empty exercise. It is relationship that will endure and relationship that will sustain the restored land […] The moral covenant of reciprocity calls us to honor our responsibilities for all we have been given, for all that we have taken. It’s our turn now, long overdue… Whatever our gift, we are called to give it and to dance for the renewal of the world. In return for the privilege of breath.” – Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants.Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013. Pgs. 338 and 384.

- The San Francisco Bay Area isn’t immune to toxicity from military waste: the ongoing redevelopment of the Bayview and Mission Bay shows the depth of environmental hazards disproportionately borne by Black and Brown communities in these waterfront areas. See the ongoing investigations being documented in the San Francisco Chronicle’s Dangerous Grounds series.

- Indigenous sovereignty movements like the EZLN continue to pave the way for intersectional social movements that center land justice, environmental thinking, and human rights. For more, see “The Zapatista Revolution is Not Over,” in The Nation, 2019.

- Glenn Albrecht coined the term solastalgia to describe “an emplaced or existential melancholia experienced with the negative transformation (desolation) of a loved home environment,” and is “is “the homesickness you have when you are still at home” Many have begun using this term, along with “climate grief,” to describe the mourning of losing vital landscapes due to climate change. AFTER LIFE artists Courtney Desiree Morris and FIFTY-FIFTY use the term solastalgia in their projects. See: Glenn Albrecht, “The Age of Solastalgia,” in The Conversation, August 7, 2012.

- On the important difference between damage-based frameworks for social explanation versus desire-based frameworks for social transformation, see Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 79, No. 3 (Fall 2009): 409-427.

- “Why 76 Beavers Were Forced to Skydive into the Ohio Wilderness in 1948,” in Running Ponies: a Scientific American blog, January 29, 2015.

- On the concept of visual sovereignty as a practice undertaken by Indigenous artists to claim agency, see: Michelle H. Raheja, “Reading Nanook’s Smile: Visual Sovereignty, Indigenous Revisions of Ethnography, and ‘Atarnajuat (The Fast Runner)’,” American Quarterly Vol. 59, No. 4 (December 2007): 1159-1185.

- To learn more about what mutual aid is and how to participate in mutual aid projects, read Dean Spade’s new book Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis and the Next, or visit the Big Door Brigade’s amazing resource website.

- Joanna Macy, “Widening Circles: An Interview with Joanna Macy,” interview by Emergence Magazine, Emergence Magazine, April 5, 2018, audio, 33:36.

- Joanna Macy, “Joanna Macy on Yoga, Buddhism, and Eco-Activism,” interview by Kelpie Wilson, Yoga International.

- Andrea DenHoed, “The Turn-of-the-Century Pigeons that Photographed Earth from Above,” The New Yorker, April 14, 2018.

- For a history of the pink triangle as a symbol of queer liberation and survival in the midst of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, read “How Six NYC Activists Changed History with ‘Silence=Death’” in The Village Voice, June 20, 2017. To learn more about Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, and STAR, listen to these incredible interviews on the blog for the Center for Women’s History at the New-York Historical Society.

- “An act of survivance is Indigenous self-expression in any medium that tells a story about our active presence in the world now. Anishinaabe scholar and writer Gerald Vizenor’s defines survivance as ‘an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name. Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy, and victimry. Survivance means the right of succession or reversion of an estate, and in that sense, the estate of native survivancy.’ Survivance is more than mere survival—it is a way of life that nourishes Indigenous ways of knowing.” Quoted in the website for Survivance, a social impact game that “asks us to explore our presence and create works of art as a pathway to healing.”