Mon April 14th Closed

Art, Education and Hustle through San Francisco Public Transit

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 U.S. Census.

Vida Kuang was raised by a Toisan matriarchy and the streets of Chinatown. She is an artist and educator. Her education is rooted in her family’s corner store, her work with youth in San Francisco, and community elders who mentor her growth. For Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? Kuang’s artworks capture brief moments she observes around San Francisco’s Muni buses. Children and parents on their way home, teenagers waiting to go to school—all the mundane moments of transportation Kuang sees as moments worth noticing.

Kuang sat down with founder of re.riddle and member of the Come to Your Census curatorial committee Candace Huey on May 12, 2020 to discuss how her work reflects how we navigate our lives and the importance of free and accessible art that resonate with all communities.

Candace Huey: Vida, thank you for joining me today. It’s a pleasure to learn more about your work and process.

Vida Kuang: Hi, Candace. Thanks for inviting me and giving me this opportunity to talk about my art.

CH: You are a native San Franciscan with roots in Chinatown. What does this mean to you? How is it, if at all, considered in your work?

VK: Chinatown is and first and foremost a working class neighborhood and an immigrant neighborhood. A lot of people from the Pearl River Delta area in Canton, China, which is in the southern part of China, moved to San Francisco’s Chinatown. I think when you look at Chinatown, it’s mostly working class people and mostly renters, so it’s a population that is both finding its footing in the U.S. and very vulnerable to American capitalism. It’s always important to me to depict working class immigrant Chinese people in my artwork because of this. While I know that China is a growing nation and is becoming more and more of an economic hegemony, we’re often not talking about working class, monolingual, immigrant Chinese people—of which San Francisco and the Bay Area has a huge population.

You can kind of see a shift in how we see Chinese people over the past three decades. Three, four, maybe six decades from the Cultural Revolution that my parents experienced, and even before then, there was a lot of starvation and poverty. There still is poverty in China, but now when people think about China, they think about a very wealthy class that is traveling and buying up land in San Francisco. We don’t think about working class people of color in general. It’s important for me to depict that because I came from a working class background and I think workers are the backbone of our culture and society.

CH: Who are the most vulnerable members of your community and how can art serve to support them?

VK: When I am thinking about Chinatown, there are several vulnerable groups of people. The monolingual, immigrant, low income Chinese folks who often face barriers because of language. Right now during this pandemic, a lot of folks are scrambling to make ends meet and trying to apply for unemployment. That’s proving to be very hard when you can’t apply for unemployment over the phone because it’s over capacity. So people are supposed to apply online, but there’s no online application in Chinese.

I hear so many stories, and I know personally of people who have five mouths to feed, have children who are not in school anymore, and both parents are unemployed and they still have almost $2,000 in monthly rent for an SRO, a single room occupancy. That’s a lot of pressure over your head. Renters are a very vulnerable population, not just in Chinatown, but throughout the city. Right now housing is so scarce and most of us don’t even know how we’re going to pay rent for the next couple of months. Sure there’s a temporary moratorium on evictions right now, but how are we going to pay it back after?

I would also say another vulnerable population are our elders. A lot of our elders are being targeted and attacked because of the anti-Asian racism from the pandemic.

I will also say another vulnerable population in Chinatown are our Black residents. Not many people know this, but we have Black people who live in Chinatown and they are a part of our community. There are daily systemic threats toward Black people’s life in the U.S. It’s also complicated living in a place like Chinatown where there’s a deep network of support and networks of mutual aid and nonprofits for the community. I can only imagine how hard that might be for a Black resident in Chinatown to not necessarily feel reflected in the neighborhood. I think the history of Chinatown has made it so that a person can buy food, can work and stay within a Chinese-speaking population and still survive. This has historically served the community in many ways but oftentimes exclude Chinatown’s Black residents.

CH: Your work touches upon themes related to race, community, class, gender, and the intersections between them. Can you tell me more about how your work in particular addresses the public? How do you define “the public”? Considering your specific characterization of “the public,” how does this shape your artistic practice? Are there any materials, tactics and techniques that spring directly from your connection with the public?

VK: When I think about the public, I think about the streets, the places that are accessible to all people and ultimately free. F-R-E-E. Free. I want to make sure that the art I make is accessible to people. Nobody should pay to see my art. It’s important to me that my work is free no matter what platform, be that through social media, or painting a mural, or putting a work up in a public, free gallery. Especially if I’m depicting people from my community. And when I say my community, I mean to say my working class community. That’s always the group of people I want to see my art.

That community doesn’t have to be just Chinese. You can be a working class person of any race or age and it’s important for me that my work resonates and has some sort of relatability. I want my audience to be like, “Oh wow, that person looks like my aunt,” or “Oh, that person is a grocery store worker. My uncle is a grocery store worker too.” As I experiment with different mediums, I also want to make sure it’s accessible to people of various abilities. For instance, when I work on oral storytelling projects, I want to make sure there’s transcribed text available or captions. This is a growing edge for me, but I want to work on this as an artist. Even though I want my art to be seen or experienced, I often draw from my core experiences in hopes of connecting and relating to people.

“When it comes to being an artist who is talking about class and race and gender, how important it is to make sure that there is equity and a responsibility in who is seeing that art and what the messaging is, and whether or not you’re crafting that messaging alongside the people you’re depicting.”

CH: Your definitions of public and community in your work are diverse and varied. It is important that your work is accessible to all, open, free and legible. In addition, it’s about providing a face, voice, and narrative to the working class communities or marginalized that may not have a platform to express themselves. Stylistically, in terms of a visual language, are there any tactics and techniques that spring directly from your connection with the public?

VK: On the topic of visual language, anyone can have a reaction or response to art, even if they are viewing non-representational art. Even if it’s the most conceptual or the most abstract art, I think anyone can have a reaction to it. It’s just that our society has made art so inaccessible and inequitable that you have generations of people who feel like they can’t enter into art spaces or don’t have anything to say about a piece of artwork or feel like they can’t express themselves through art. There’ve been so many times where I brought my mom into galleries and she’s just like, “I don’t get it.” And I’m like, “Mom, you don’t have to get it. What do you see? What do you feel?” And sometimes when I probe her more she shares very profound, thoughtful responses.

I think that’s kind of a part of my mission too as an artist. When I’m talking about accessibility, I’m not just talking about entering into a physical space to witness or see art, but it’s also important to have a stake in engaging with art. I often say to myself that my goal is that if my mom can understand it—being a woman with an elementary school education having grown up during the Cultural Revolution in China—if she can feel like she understands my art, then I’ve done my job. It doesn’t matter if I can get great press, or get recognition elsewhere, I’ve accomplished my goal if my mom can understand my work.

That’s what I think of when I think about visual language. And my perspective comes from my past experience in Chicago talking to elementary school kids about art. I was a docent at the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago. We’d bring kids in and it was so amazing to see them feel empowered to talk about art. It’s hard because often our art in museums in the U.S. are not representative of working class people of color. It’s rare to see. In the last century, people in the U.S. are beginning to understand how eurocentric a lot of art institutions are. Artists of color have always been around and have been depicting their own communities. We’ve always been around.

CH: Can you tell us more about your work presented in Art+Action and YBCA’s art and civic experience, Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?

VK: It started with my partnership with CCDC, the Chinatown Community Development Center. We were talking about thinking about public transit in San Francisco. I thought about combining my own experience growing up in the city and taking public transportation my whole life with this history. I then pulled in my artist friend Bijun Liang and we started talking about a larger artwork that could respond.

Prior to this, I learned of a really incredible woman named Enid Ng Lim. She brought in the 10 and the 12 bus lines into Chinatown. Before her efforts, there weren’t that many bus lines running through Chinatown. You can say a lot about the reasons why. It’s because of red lining, it’s because of racism. If you’re a resident, you need to stay within these parameters. Chinatown is seen as a ghetto. So there’s this incredible Chinese American woman who brought these bus lines in, and the bus lines today go into the General Hospital and into the Southeast, and that’s so important as a means for connection. Especially for monolingual immigrant Chinese folks to get to other parts of the city.

These bus lines allow people to get access to other forms of care, like healthcare, social services, food banks, et cetera. That fight for the kind of transit system we have today is also because of public school youth who fought for Free Muni for youth and elders. With this series, I wanted to depict how a lot of that activism came from Chinatown. Like the youth from Youth MOJO in the Chinese Progressive Association campaigned for free Muni for youth and have testified about their own experiences. There’s always more we can do to improve our transit system. So it was important to me to depict how transit justice has evolved over the past few decades and what it brings to us today.

There’s also a lot of politics around taking the bus on Muni because it’s mostly working class low income people. Sometimes you’ll have some office workers or tech folks who are coming in and out of the financial district, but mostly it’s youth who are coming out of school, our elders, and working class people who are taking their bus to their jobs, houseless people—and a lot of things can be happening. There can be a lot of racial tensions. I think when we talk about San Francisco, a lot of our places and communities of color have been gentrified, but when you are taking the bus, you really get to see the real San Francisco that’s always been here.

CH: Your work’s focus on public transit is all the more relevant this year as it pertains to the 2020 Census. It is paramount that each SF resident is seen, counted, and receives his/her fair share of federal funding for their neighborhood—such as public health coverage, education, community programs, and public transportation. Your work vividly illustrates multiple narratives of the distinct and diverse people that ride the bus lines, and their interactions and intersections with one another.

VK: I would say at least in the series, it’s about past advocacy to bring MUNI into Chinatown and how Chinatown residents and workers use the bus. Folks going into Portola and parts of the Bayview from the 8, for example. People could do whole documentaries and write papers about the 8. Just take the 8 one day and experience it for yourself. There’s the 10 and 12 that go into Potrero Hill, and there’s also the 1 bus that goes into the Richmond. And some of these buses like the 30 and 45 connect people to other parts of the Bay area.

My mom takes the 30 and 45 to go to Oakland. I want to pay homage to the fact that a lot of these bus lines were created because the community fought for them. It can be hard to depict because you also see the ugly side, where people are fighting for resources. Resources like fighting for a seat on the bus, or for some kind of space, or jumping onto the bus because you need to go somewhere but you have no bus money.

“When we talk about San Francisco, a lot of our places and communities of color have been gentrified, but when you are taking the bus, you really get to see the real San Francisco that’s always been here.”

I wrote on one of the artwork panels that public transit shows the real SF hustle. Each of the wooden panels on the sides have notes from observations from sitting on the bus growing up. It could be a grandma and her child splitting a bao after school, or elders going to the food bank with their little trolleys. You see people laughing and you see people fighting. You see people caring for each other. Muni has a lot of stories.

CH: What, in your opinion, is currently an urgent issue for artists and artistic practice?

VK: I think there’s a lot going on. There’ve been a lot of social and political noise in the past few years. I mean, it’s always been going on in the U. S., but I think people are feeling it more so because of 45’s administration. People are feeling it intensely in San Francisco, given how the wealth gap in the city is so extreme. In San Francisco you’ll see a high rise or a Salesforce building, and right around the corner you’ll see a homeless encampment. I think there is a responsibility, especially for artists who are from the Bay, to show that reality. But do it in a way that’s not extractive or exploitative.

I’m someone who grew up in Chinatown and I’ve seen a lot of artists just kind of “parachute” in. It could be like parachute artists or scholars or documentary filmmakers. People come into communities of color and just kind of co-opt or take our stories, take our experiences, and then just run off with it. Maybe a woman’s story about living in an SRO and about being a fishmonger. Her story is being depicted on the big screen and in a film festival in this very large theater before a crowd that would only “experience” poverty / working class conditions through a screen. They only see her in the film but don’t really get a chance to meet her or talk to her. Her story is only given legitimacy because it’s through an artist, scholar, filmmaker, or someone else crafting the narrative.

[Image: an illustration of an elderly woman, her back facing the viewer. She is walking and carrying a bag of groceries on one hand and pulling a trolley bag in the other. There is text surrounding her in Chinese and English]. Find more of the artist’s work on Instagram @vida.kuang

So I’m thinking about when it comes to being an artist who is talking about class and race and gender, how important it is to make sure that there is equity and a responsibility in who is seeing that art and what the messaging is, and whether or not you’re crafting that messaging alongside the people you’re depicting.

It’s important for me to also support and help nurture artists who are from the communities that I’m talking about. If there’s anything that I can do in my power, I want to support the growth of more artists from the grassroots. Even if they never went to art school. I never went to art school. With some mentors and myself, I’ve learned all I know through practice. To be able to just kind of learn how to convey a message through a visual medium or performance medium, I think that’s very powerful. I think everyone has that story to tell. I really am a firm believer that anyone can be an artist. You just have to really think intentionally about the messaging and keep working at your craft. And that’s just something I’m doing all the time as an artist myself.

CH: Thank you so much, Vida, for sharing your insights about your work, process, perspectives, and for being part of Art+Action and YBCA’s art and civic experience.

VK: Thank you for having me. Candace.

CANDACE HUEY

re.riddle’s founder and principal, Candace Huey, brings her extensive knowledge of and experience in the art world to her projects. Huey has worked for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bonham’s auction house, Alameda County Arts Commission and various galleries in the Bay Area where she curated exhibitions showcasing the work of 20th century masters and contemporary artists. As an independent curator, she conceptualized and produced exhibitions for cultural institutions such as Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco, Consulado General de México, Consulado General de España, and Consulat Général de France, San Francisco. She consults on collection portfolio and development for private clients in San Francisco, Hong Kong, Chicago, London and Paris.

Huey holds degrees from The Courtauld in London and U.C. Berkeley, and has presented her academic research on 17th century Dutch Art at renowned conferences in the United States and the Netherlands. She currently teaches art history at a private university, sits on the executive council for SECA SFMoMA, de Young Museum College Programs Advisory, ArtTable and is an active member of Artadia San Francisco Council and Headlands Center for the Arts.

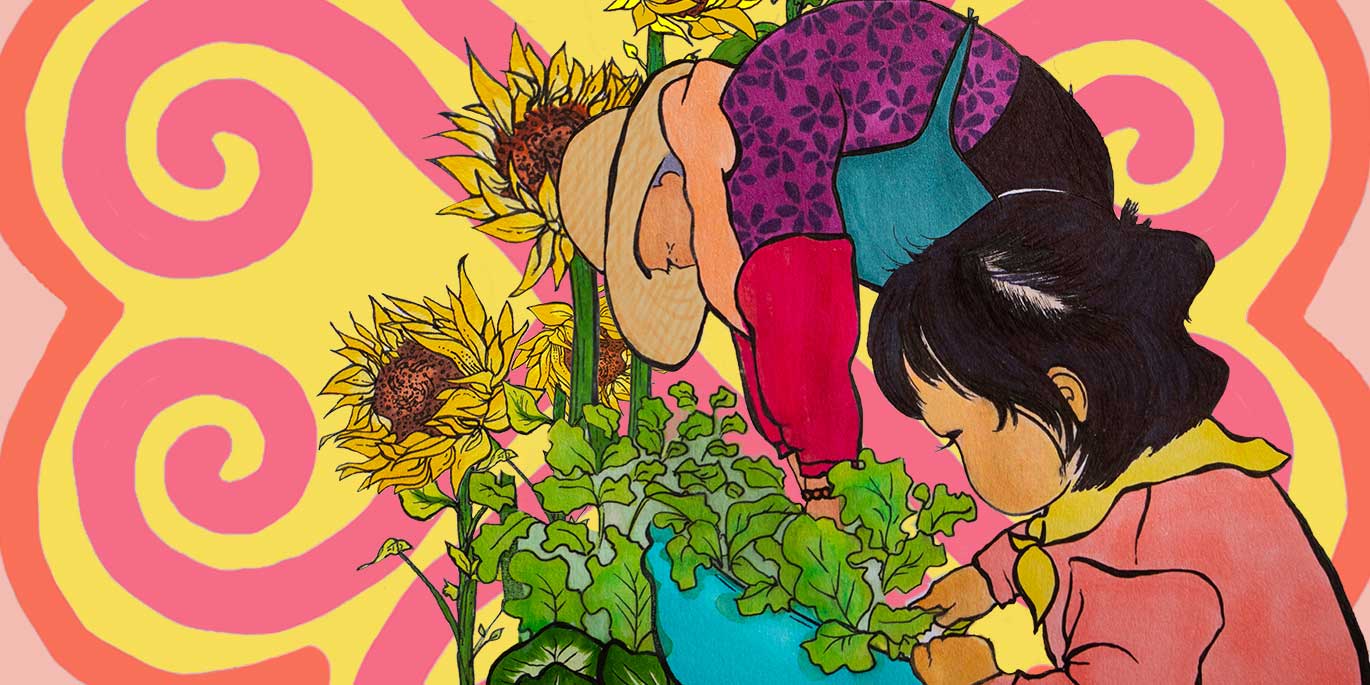

Lead image: Vida Kuang, detail of we make magic out of seeds, mixed media.

[Image: A child and her grandmother harvesting greens from a garden full of sunflowers and collard greens. Behind them is a symbol inspired by Hmong embroidery paj ntaub. Encircling them are the words: Every seed matters, every person matters. Census 2020. We make magic out of seeds.] Find more of the artist’s work on Instagram @vida.kuang