Thu April 25th Open 11 AM–5 PM

Building Stronger Communities: A Conversation with the Chinatown Rising Filmmakers

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 U.S. Census.

On May 11, 2020, Candace Huey, founder of re.riddle and member of the curatorial committee for Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?, sat down with documentarians Harry Chuck, Josh Chuck, and James Q. Chan to discuss their film Chinatown Rising.

Candace Huey: Hi Harry, Josh, and James. Excited to speak with you today about your film, Chinatown Rising, and how its themes pertain to the 2020 Census—specifically galvanizing your community to claim its fair share and representation.

Against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-1960s, a young San Francisco Chinatown resident armed with a 16mm camera and leftover film scraps from a local TV station, turned his lens onto his community. Totaling more than 20,000 feet of film (10 hours), Harry Chuck’s exquisite unreleased footage has captured a divided community’s struggles for self-determination. Chinatown Rising is a documentary film about the Asian-American Movement from the perspective of the young residents on the front lines of their historic neighborhood in transition. Through publicly challenging the conservative views of their elders, their demonstrations and protests of the 1960s-1980s rattled the once quiet streets during the community’s shift in power. Forty-five years later, in intimate interviews these activists recall their roles and experiences in response to the need for social change.

CH: Harry, what is at stake for you and your community by taking the Census?

Harry Chuck: Well, as we approach the middle of 2020, I find myself along with other Americans deeply concerned about our futures. Everything seems to be coming apart with the pandemic and the list of our collective problems is long and continues to grow. At the moment we see no end in sight. Everyone’s reaching out for answers because we have never been in a crisis like this, and we’re all looking to the government for leadership, for guidance, and resources.

Every day, it becomes clear to me that even our government, our government leaders, and leaders throughout the world are unclear about where to begin There are many suggestions, but few answers or solutions because everyone is struggling from the top down. The stakes are higher than ever. We must work closely with our elected leaders to identify the needs that are unique to our communities.

Our family lived in San Francisco’s Chinatown for over four generations. And for much of that time, Chinatown was characterized as insulated and isolated. Often we would describe it as an undeserved, underserved, immigrant community, but it has managed to survive major disasters, including earthquakes, epidemics, poverty, and social chaos. So looking back, many of those trials would have been better addressed if the conditions of the community had been better understood by elected government officials. I’ve known a few local Census workers and advocates over the years and they’ve been pretty good. They’ve been actively promoting the importance of the Census, but this year it’s a little bit different because people have noted that there are concerns and feelings of reluctance towards participating in the 2020 Census. These are primarily from people of immigrant status, who are concerned with their noncitizenship status, and they fear the threat of deportation or separation from their families.

Another closely related concern is how personal information will be used once it becomes part of the federal data bank, and would this lead to inquiries from other government agencies. So back to our own family, in fact, because of long historical memories and oral histories, the issue of trust continues to be a major concern. Can we trust the process? There are probably many more concerns, but for the people transitioning as new immigrants, this is highly important. I really believe that the stakes are higher than ever and that we should strive for active participation from our communities in the 2020 Census. I’m confident that we can successfully gain the cooperation of our communities if we can show them how the Census is used to achieve a better understanding of local demographics, and how this leads to a fair apportionment for serving the documented needs of the people—documented and undocumented. I think politically, people may not realize that the Census leads to a fair distribution of representative leadership that serves the common good of our citizens.

We must establish trust with our people that this is a fair process and it ensures their privacy and that only good things can come out of this, especially during this period of the virus pandemic because we’re draining our resources. The Census enables us as citizens to participate in building stronger communities and invites us every ten years to exercise our collective responsibilities as citizens. As the world changes, so will our communities. The Census invites us to anticipate and plan for the future of our families and neighbors.

CH: Josh, how does your work lend itself to activating social and political reform?

Josh Chuck: I think positive change in our communities doesn’t happen all at once, it’s an accumulation of a lot of little steps. It begins with the mindset of the individual. It’s up to us to look around and ask, what do we see that’s unjust in our communities? I know for me, sometimes problems in society feel so big and overwhelming that I don’t feel I even want to try sometimes. It’s really helpful to see examples that change is possible.

Our film tells the personal stories of individuals just like ourselves, who are sacrificing and risking their lives for the good of the community. They didn’t have any role models to follow, the deck was really stacked against them, but they tried anyway. I’m hoping that putting these stories on the screen can inspire all of us to get out there and try to do what we can to activate the reforms that we need. And again, it just starts with small steps. We need to know that just one person, no matter what your background or your situation is, can make a difference. The first step is to stand up and be counted and let your voice be heard.

CH: In what ways must we be cautious about employing certain images that might be generative and perpetuating norms that are restrictive or reductive rather than expansive?

JC: That’s definitely a danger that we had to keep in mind. Grouping people in one-dimensional categories means I’m assuming that everyone’s kind of the same, and that matters when we portray individuals, especially when I think about Asians, on the screen. So one of my favorite things about our film is that the activists that we interviewed were each very unique and showed strength in different ways, that isn’t often seen in Asians onscreen. Someone told me after they watched the film that they were just blown away by all of these bad-ass Asians, which I appreciate because I feel the same way. It goes against the stereotypes that a lot of the mainstream believes in. So for me, the bottom line is we just need to hear more stories, so everyone can believe that their own stories and their own lives matter because they all do. Everyone is important and can inspire others.

CH: Harry and Josh, how can previous generations connect and motivate younger Asian Americans to stay vigilant and active?

HC: Both Josh and I have been youth workers and we have the privilege of tracking many of them from childhood until they’re young adults, and sometimes even beyond that. We see how leadership is shaped, that it seems to be a pattern and a process in which young people catch onto things, how they begin to develop their values, and how those values shape the way they make decisions.

It’s important for each generation to take a younger generation under their wing and to share our experiences with them, not tell them what to do, but just let them know that we are all a product of the decisions we’ve made and we’re proud of the way other people live their lives.

JC: I think it is definitely important to tell stories, but it’s also important to listen to the young to see what’s going on. Sometimes we underestimate how thoughtful and insightful young people can be, and then if they share with us what’s going on in their world, it’s up to an older generation to encourage young people today to do something. A lot of Asian Americans, especially in the Bay Area, are kind of no longer faced with this blatant racism, because a lot of Asian Americans in the Bay Area are kind of now part of the mainstream, unlike previous generations.

I think it’s important that we encourage young people today to be allies. The activists in our film, they couldn’t have done what they did for the Asian American movement, without allies in the Civil Rights movement, or allies from all the minority groups, and also Caucasian people. So now that Asian Americans are in a certain position to be that ally, I think it’s important that we encourage young people to look around outside of just their own little circle and see how they can help others.

CH: James, who are the most vulnerable members of your community and how do you support them?

James Q Chan: Many of the social issues highlighted in our Chinatown Rising film of the ’60, ’70s, and ’80s, are still topical issues today. The work continues around affordable housing, working class rights, immigrant rights, and senior and youth services. With the sheltering place ordinance during this pandemic, our most vulnerable members of our community are now front and center. The families who live in the densely packed SROs, single room occupancy, with communal kitchens and shared bathrooms. Their young children are home from school confined in close quarters, low wage workers, many who rely on service jobs, restaurants, and domestic care, are pretty much all out of work right now.

On top of that, we are painfully witnessing the rise in Anti-Asian and xenophobic sentiments, both locally and nationally, so it’s pretty much all emotionally and spiritually depleting. But Harry previously mentioned how San Francisco’s Chinatown has survived many crises, so how do we offer support to our most vulnerable community members during this public health and economic crisis? These are questions that I ask myself daily, but during this extraordinary time and unparalleled time that we are in, I find that our survival instincts are kicked into gear, we bend. We are a resilient people.

Chinatown has been blessed by so many grassroots organizations that are offering lifelines right now, for instance the Chinatown Community Development Center, Self-Help for the Elderly, Chinese for Progressive Associations, they have all organized mutual aid support along with hundreds of volunteers. They show up daily to serve their membership and the community of Chinatown. For instance, CCDC, whose work primarily has focused on housing, has focused on feeding the community, particularly the vulnerable communities in SROs, by providing lunches to help alleviate the overcrowding in their communal kitchens. They’ve also partnered with local restaurants to provide daily lunches. So right now, if you’re asking how we can support individually and collectively, if you are unable to offer hands on volunteering and you are financially capable, consider donating whatever you can to these organizations. To me, these necessary acts of compassion are the power of community to ensure that our most vulnerable members and their survival and wellbeing are sustained now in this time and beyond.

and Chinatown Rising team members.

CH: Josh and James, what has been the response from your peers about the messages in this film? Were there any sentiments about carrying on community activism by the younger generations?

JQC: The message in Chinatown Rising is that the work is not done. That the service these incredible activists did on the front lines during the ’60s and ’70s, has carried to this day. And I feel like right now, after screening the film and seeing all of the incredible responses, that the bottom line is that you serve your community, you find a way to serve the people, serve the youth—and to me, those in the front always reach back.

JC: For me, I’ve heard all kinds of responses from my peers. People my age didn’t live through the time period in Chinatown Rising. I was born and raised in Chinatown and Harry is my dad, so it surprises some people that I didn’t know about any of these events really. I didn’t know any of these activists, and I didn’t even know most of my dad’s life story. These events were only a decade before we were born, but for us to not know anything about the struggle and the strength that our people showed, got a big response from my peers. I think of the pride this history gives me, and I think everybody should know these stories.

One friend started interviewing all of his family members to hear their stories, so I thought that was a really cool thing. Someone bought 50 movie tickets for young people to watch our film. People need to know, because it’s important to appreciate how we got here, where we are today. I think my dad said this earlier, it’s not out of thin air, we didn’t just show up and find ourselves in this situation.

Something else that I’ve heard from peers is that the film shows people reflecting on their lives and expressing how meaningful it was for them to be involved in community activism. I think it’s inspired people to think ahead and say, “What am I going to feel, more towards the end of my life? How do I want to look back? And am I going to be proud of what I did and what I stood for?”

CH: Thank you, Harry, Josh, and James, for your continued efforts and inspired activism.

ABOUT

HARRY CHUCK

Co-Director, Producer, Director of Photography

Former Youth Director and later Executive Director of Cameron House, Harry was an early mentor for hundreds of Chinatown youth including author/activist Gordon Chin. Harry was the catalyst in Chinatown’s fight to save the Chinese Playground from being developed into a parking garage, leading to the formation of the Committee for Better Parks and Recreation in Chinatown. He was co-founder of the Chinatown Coalition for Better Housing, which led the fight to develop the Mei Lun Yuen affordable housing project. He was appointed by four separate mayors to city commissions which included the Public Housing Authority and Juvenile Justice Commission. Harry was one of the first Asian American religious leaders to speak out for same-sex marriage. In 1981, he earned his MA from the SF State University’s Film Arts Department where he served as a p/t student assistant in film history. His footage for this film was shot as a student/activist and Chinatown Rising is his official return to filmmaking.

JOSH CHUCK

Co-Director, Producer

Josh grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown and has worked in the community for over 16 years as a youth worker, filmmaker, and fundraiser. He has produced, shot, and edited short films, mostly sharing the stories of individuals who symbolize the rich diversity of the city, as well as organizations advocating for the needs of the underserved. He currently directs the UPS Community Internship in San Francisco, an intensive community immersion program for UPS Upper Management, which focuses on the Chinatown, Tenderloin, and Bayview neighborhoods. He enjoys international travel, often spending months at a time overseas. To Josh, the best part of travel is learning about other cultures, meeting inspiring individuals, and playing basketball with the locals.

JAMES Q. CHAN

Producer

James Q. Chan is an Emmy-nominated director and producer based in San Francisco. His film training/mentorship began alongside two-time Academy-Award winning filmmakers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman (The Times Of Harvey Milk; Common Threads). Producing credits with Epstein & Friedman include History Channel’s 10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America (Emmy® Award; Outstanding Non-Fiction Series), HOWL (Sundance Opening Night; National Board of Review Freedom of Expression Award). Other producing credits include Puck And The Riddle Of Codes (IDFA; Dutch Television VPRO); ISTINMA (Best Short, American Indian Film Festival; Smithsonian Native Showcase); Entry Denied (Jury Award, Best Short, Provincetown); Right Down The Line music video for Bonnie Raitt’s Grammy-Award winning album “Slipstream.”Prior to filmmaking, James worked as a SAG/AFTRA Talent Agent in San Francisco.

James directed and produced the Emmy® Award nominated documentary Forever, Chinatown (Best Cinematography, Los Angeles Pacific Film Festival) a meditation on memory and community seen through the lens of an aging artist’s miniature dioramas of his childhood Chinatown. The film received multiple festival audience and jury awards, a national public television broadcast on PBS/World Channel and was selected for the American Film Showcase, the premier film diplomacy program between U.S. State Department and USC School of Cinematic Arts, where James served as an envoy to Turkmenistan in 2018. James is the founder of Good Medicine Picture Company and is a recipient of a Certificate of Honor from the San Francisco Board of Supervisors for his work in amplifying stories from the APA community, immigrant voices, and tenant struggles. James is a member of the Directors Guild of America.

CANDACE HUEY

re.riddle’s founder and principal, Candace Huey, brings her extensive knowledge of and experience in the art world to her projects. Huey has worked for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bonham’s auction house, Alameda County Arts Commission and various galleries in the Bay Area where she curated exhibitions showcasing the work of 20th century masters and contemporary artists. As an independent curator, she conceptualized and produced exhibitions for cultural institutions such as Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco, Consulado General de México, Consulado General de España, and Consulat Général de France, San Francisco. She consults on collection portfolio and development for private clients in San Francisco, Hong Kong, Chicago, London and Paris.

Huey holds degrees from The Courtauld in London and U.C. Berkeley, and has presented her academic research on 17th century Dutch Art at renowned conferences in the United States and the Netherlands. She currently teaches art history at a private university, sits on the executive council for SECA SFMoMA, de Young Museum College Programs Advisory, ArtTable and is an active member of Artadia San Francisco Council and Headlands Center for the Arts.

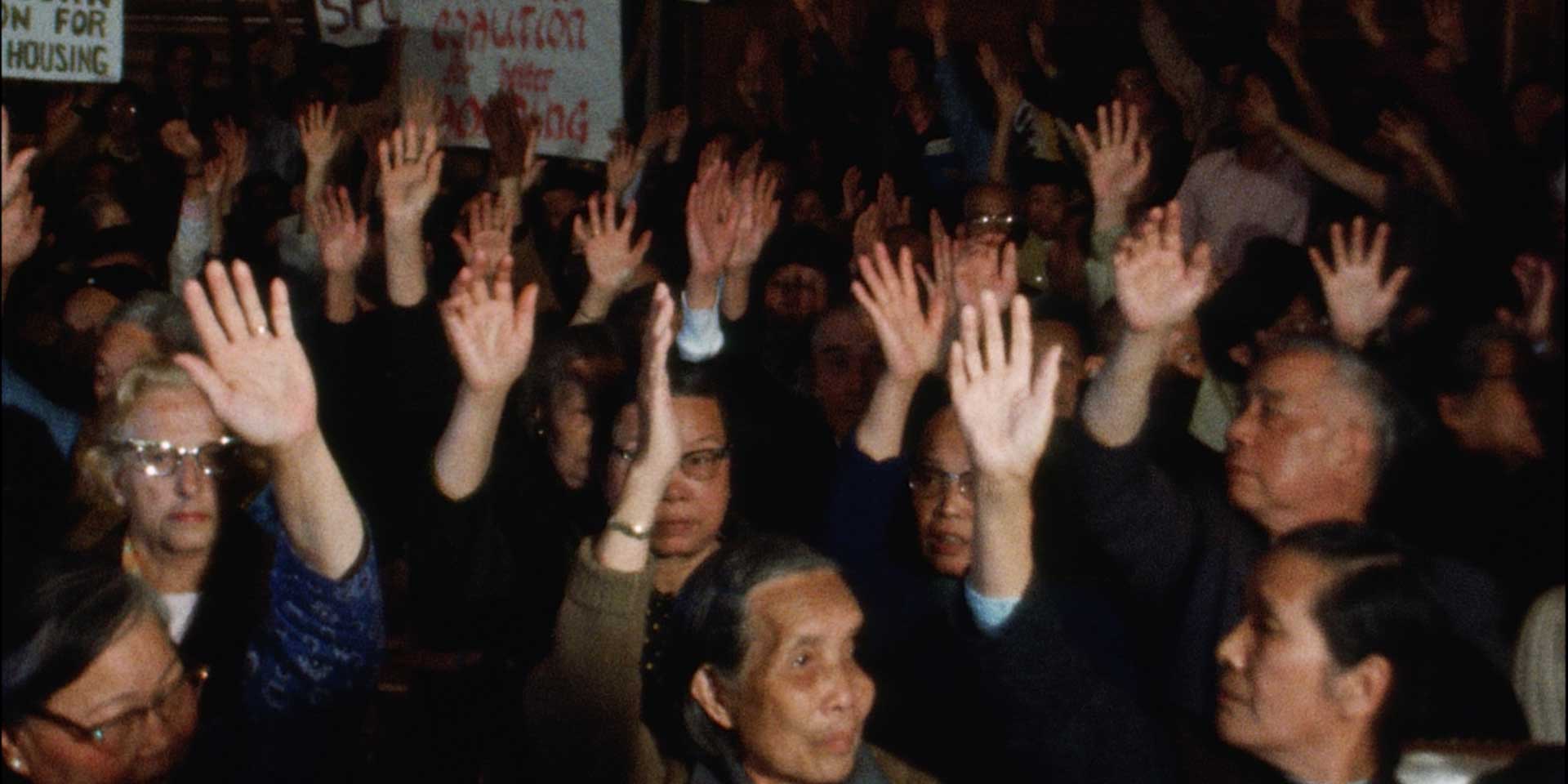

Lead image: Harry Chuck, Old Ladies 2: Seniors and others in a City Hall hearing advocating for more affordable housing in Chinatown, San Francisco, photograph, San Francisco.