Thu April 25th Open 11 AM–5 PM

Meaning, Survival, and Power in Visual Culture

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

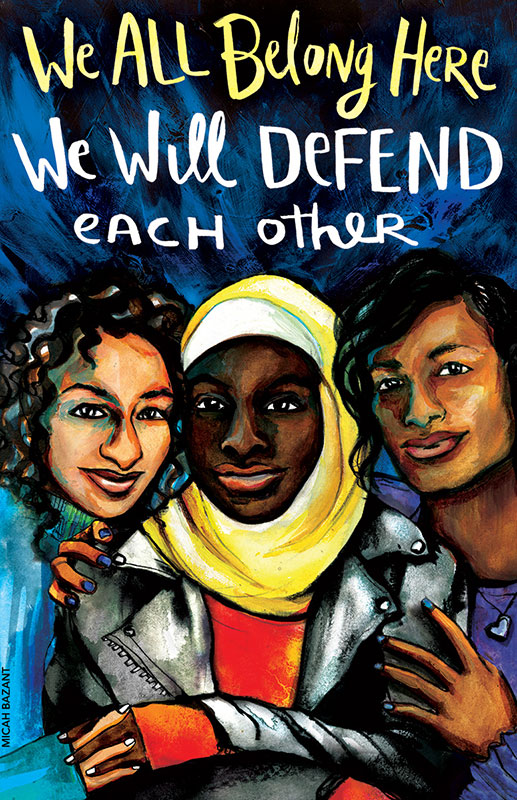

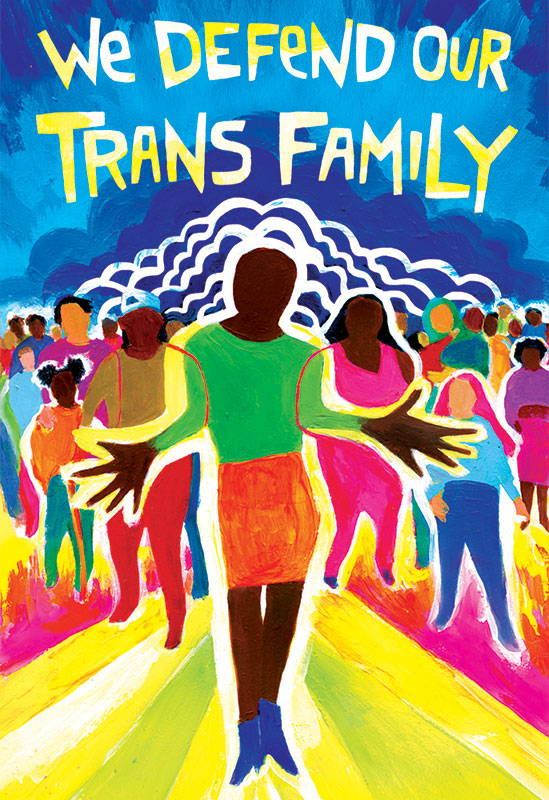

Micah Bazant is a trans visual artist who works with social justice movements to reimagine the world. They create art inspired by struggles to decolonize ourselves from white supremacy, patriarchy, ableism, and the gender binary. They make art as a practice of love and solidarity with trans liberation and racial justice movements to build power.

Bazant sat down with YBCA Curatorial Project Manager Fiona Ball to discuss how art can play an activist role in both short and long term solutions.

Fiona Ball: How did you first develop your artistic practice?

Micah Bazant: As a kid I was always making things, but I stopped making art for over a decade in my 20s while I was struggling with anti-trans oppression and severe depression. I came back to art through the support of friends and mentors in social justice movements, through organizers like Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, Patricia Berne, Mariame Kaba, and so many others who believe in the power of art to reimagine the world. They encouraged my work and gave me opportunities to create. And I was inspired by seeing the work of local artists like Dignidad Rebelde, Emory Douglas, Favianna Rodriguez, etc., who demonstrated that there is a role for artists in our freedom struggles. So many artists and designers shared information, skills, and resources with me—everything from how to sign my first prints to how to collaborate with community organizations.

I believe great art emerges through networks of relationships, and I aim to give back the kind of generous support I’ve received, especially to emerging artists who want to work with liberation movements.

FB: Your work is often collaborative, how do these partnerships take form?

MB: So many different ways. Sometimes organizers or community members reach out to me. After the 2016 election, I started getting messages from teachers across the country, saying “my students are terrified, they are afraid to come to school, can you make something for classrooms?” Students were afraid of being deported, afraid of growing white terrorist violence, etc. This led to creating the We WIll Defend Each Other poster in collaboration with five national organizations, and distributing them to schools and communities across the country along with a K-12 curriculum about resisting racism and bigotry.

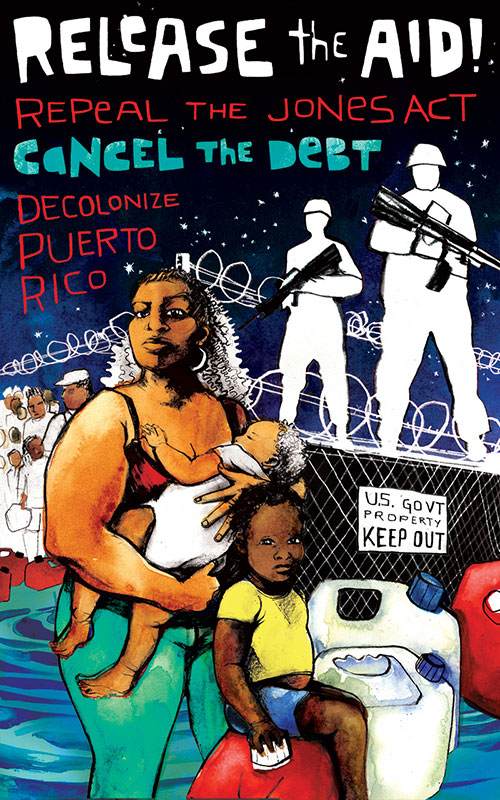

Other times I reach out to organizers to see if we can create together. For example, after Hurricane Maria I reached out to friends at the Puerto Rican art collective AgitArte. They were doing incredible mutual aid work all over the island, and saw thousands of people dying and federal aid being withheld. The scale of the crisis wasn’t being reported in mainstream media. Together we created a poster to amplify their needs and demands, help raise money, and share crucial solidarity information.

My work is relationship-based, meaning that my best work emerges out of relationships of trust and solidarity. Creating collaborative work across differences of power requires building trust, and this is definitely true for me as a white trans artist trying to make work in service to racial justice movements. Building trust often means asking how can I first be of service to your community, which doesn’t always mean creating art together. It might mean making business cards, or washing the dishes, or picking up trash. It means demonstrating humility and an ability to listen and follow the leadership of Black, Indigenous, and people of color communities. I definitely make mistakes and like all anti-racist work it is a lifelong commitment and process.

FB: Your practice creates timely visual responses to the political issues in the moment, why is this quick responsiveness important to your work and the communities you advocate for?

MB: As we’ve seen in the last few months, conditions can change extremely quickly. I learned from Palestinian and Black organizers that liberation work is both a very long game, and that sometimes conditions change suddenly, offering openings for transformation. As Arundhati Roy said, this pandemic “is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next,” and certainly the nationwide Black uprisings are a portal, opening new victories for abolition.

Liberation work requires both stamina and agility. We need to do the long-term slow work of building our skills, relationships, art, and frameworks for the world we need. And then in the rare times when portals open, we are ready to move quickly and strategically and use the momentum of the moment.

Rapid response has been a big part of my work—pulling an all-nighter to create an image to help free someone from detention when they are suddenly offered bail, or creating art to process our collective grief when another Black trans sibling is murdered. I love this work, and it plays an important role in the creative movement ecosystem, but I’ve also been trying to slow down and work in a more sustainable, less crisis-driven way.

FB: How do you connect your work to the 2020 Census?

MB: We all deserve well-resourced schools, healthcare, food, housing, and safe communities where we can thrive. Black, Indigenous, Brown, disabled, poor, and trans communities have always been denied these basic opportunities to thrive. We are fighting for these things in so many ways, from campaigns to defund the police, to creating our own clinics and reclaiming vacant housing. The 2020 Census is a crucial tool in our toolbox to gain these resources and political representation. This struggle for power, resources and liberation are central to my work.

FB: How do you think forms of visibility have changed in response to COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement?

MB: I don’t know if they have changed, but I see them intensified as we live through accelerated struggles for meaning, survival, and power in visual culture. This moment is teaching me so much about how culture functions! We’re seeing how public Black Lives Matter murals, or the removal of racist statues can reflect true shifts in power when they are led by Black communities. And at the same time seeing politicians, police, corporations, etc. trying to manipulate the visual culture for their own interests, and trying to stifle rebellion by offering symbolic concessions while they continue the same murderous policies. For example, the D.C. Mayor painting a huge “Black Lives Matter” on the street—and then watching BLM DC organizers brilliantly add “= Defund The Police”—is an incredible case study in struggles for control over narrative. Visibility is important to building power, but visibility alone is not power.

This moment is making me understand Ella Baker’s famous question to organizers “Who are your people?” in a new way. We need to ask this about every creative endeavor. Who are this art’s people? Who made it, claimed it, informed the ingredients and circumstances for its creation? Who lived the struggles it claims to uplift, and were they part of its creation? Are they benefitting and profiting from its life in the world?The meaning and power of our art is inextricable from the story, people, process, and legacy of that art’s creation.

FB: How are you taking care of yourselves? Of your community?

MB: My friends and I are trying to care for each other despite missing each other. We continue to do a lot of the same things we did before that help us stay alive—sharing food, medicine, emotional support, money, rides. Giving rides to undocumented friends coming home from work, when police are out arresting people for being out after curfew. Slowing down and emotionally supporting each other when the latest white supremacist attacks happen. Having very frank conversations about what we want if we get sick and how we’d prefer to die. So many disabled folks are being killed by discriminatory triage practices in hospitals, and some of us would rather die at home than in a hospital COVID ward alone and dehumanized.

FB: Are you working on anything in response to the current crisis that you would like to share?

MB: At this exact moment I’m working on a portrait of Syiaah Skylit, a Black trans woman whose life is in danger at Kern Valley State Prison. As an incarcerated person she’s not only 300% more likely to die of coronavirus, as a Black trans woman she’s also trying to survive ongoing assaults by prison staff and incarcerated men. Transgender Advocacy Group is creating a petition for her release and we are creating some art to amplify the campaign. Follow @micahbazant on Instagram to get updates on supporting Syiaah.