Tue July 1st Closed

Ashara Ekundayo in Conversation with Lava Thomas, Part 1

Practice, Labor, and Leadership

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

Ashara Ekundayo is an independent curator and cultural organizer in Oakland, California. She is a member of the Art+Action Curatorial Committee—comprised of Martin Strickland, YBCA’s Associate Director of Public Life; Sarah Cathers, YBCA’s Director of Public Life; Amy Kisch, Art+Action Founder + Artistic Director of Social Impact; Brittany Ficken, Art+Action Executive Producer + Project Director; and Candace Huey of re.riddle, which initiates conversations about the Census and visibility. Specifically, Ekundayo’s work and social practice centers the lives, creative labor, and archives of Black Womxn and Femmes through exhibition and public cathartic ceremony.

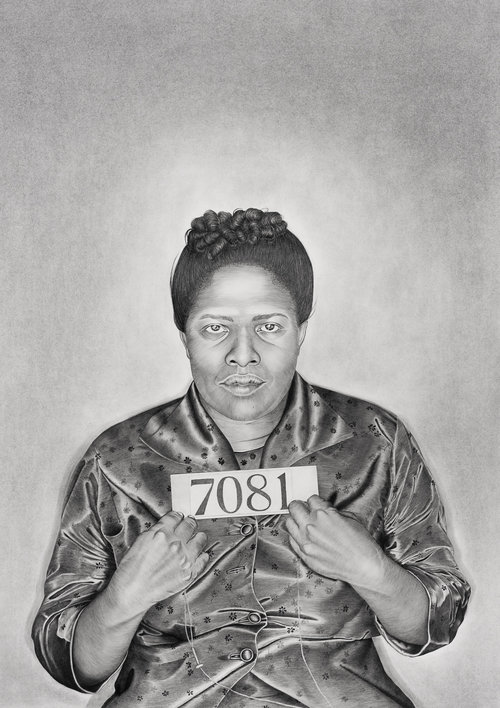

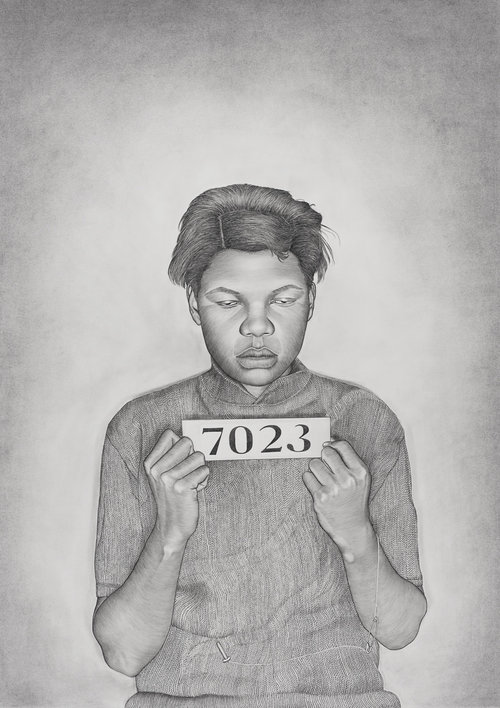

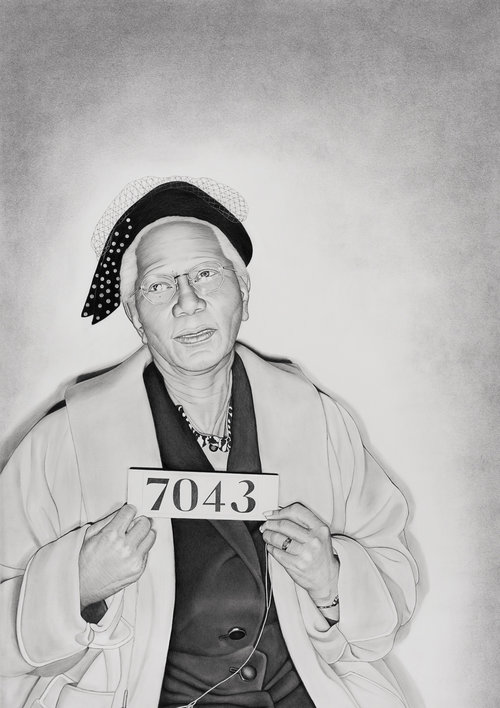

This is the first in a three part series of conversations with Lava Thomas —whose artwork is also featured in Art+Action’s city-wide outdoor campaign, as well as in the coalition’s free open-sourced digital toolkit— and serves as a precursor to a two-part panel discussion called See Black Women, moderated by Ashara and in conversation with eight Bay Area Black Womxn artists and curators to talk about visibility, grief, pleasure, and our present paradigm shift in culture and practice. Join us for a two-part conversation that will take place on Tuesday, May 19 and Tuesday, May 26 from 4-5:15pm PST. Participants include Asya Abdrahman, Sydney Cain, Erica Deeman, Angela Hennessy, Tahirah Rashed, Lava Thomas, Sam Vernon, and Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo.

Ashara Ekundayo: I have the honor today of being able to visit with multidisciplinary artist Lava Thomas, based in Berkeley, California. We’re just down the street from each other right now. Welcome, Lava. How are you today?

Lava Thomas: Thank you. I’m well. How are you?

AE: Well, sheltering in place. This opportunity to spend a little bit of time with you today is really important and special. I want to talk about a few different topics. The first being your art practice and the making of a practice in your life and in a specific place. You were raised by a large matriarchal family, a circle of women in Los Angeles. I have been thinking about the term womanish and the experience of being raised by women. Could speak a little bit about your practice in this way?

LT: I was raised by my grandmother, my grandmother’s sisters, and my great grandmother in Los Angeles. These women were from the South, originally from Decatur, Texas. My family migrated to Los Angeles in 1943. I grew up listening to stories about the South and their lives there. They were surrounded by women who were very industrious and hardworking, who essentially worked and sacrificed with little or no recognition. It was a very loving family. It’s a little stereotypical to say that I was raised by strong Black women, but they were, in fact, strong Black women.

The word womanish is funny because it’s such a southern word, but it’s important to note that the term womanist comes out of womanish through Alice Walker’s lexicon. I am indeed a womanist and was called womanish growing up because I’m the oldest in my family and had a lot of adult responsibilities as a child.

I create art through the lens of being the daughter and the granddaughter of southern women and listening to their stories, their struggles, their sacrifices, their desire for freedom under Jim Crow segregation, their stories for freedom as they were struggling in relationships where they were mistreated. These experiences color just about everything that I do. My practice is very much about giving voice to Black women, and particularly giving voice to Black women in the struggle for equality by highlighting the leadership and the labor of Black women—the under-acknowledged leadership of Black women in the Civil Rights Movement, for example, or looking at illnesses that strike Black women in higher incidences than they do other female populations in this country. These themes are also colored by the experience of the women in my family. My work very much centers the lives of Black women.

AE: Let’s talk a little bit more about making visible women’s labor in the Civil Rights Movement and your work framed by freedom workers, human rights, and civil rights. Even in this time of COVID-19, the work of women of color is not really being talked about in the media. Let’s pull the thread on women’s labor being made visible in times of catastrophe.

LT: Women’s labor now, Black women’s labor now, in the time of COVID-19, is urgent. We are on the front lines in so many ways battling this disease, from Black women mayors in this country who are fighting for policies for federal dollars for their cities. Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot who was one of the first mayors to really talk about the racial disparities and how COVID-19 is devastating Black communities in Chicago, and San Francisco mayor London Breed established early restrictions, shelter in place orders, and social distancing to keep San Francisco and the Bay Area safe. Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms is urging folks to stay home despite Governor Kemp’s order to reopen the state of Georgia. Washington D.C. mayor Muriel Bowser is creating a ReOpen D.C. Advisory Group and has tapped Michelle Obama and Susan Rice.

We have Black women at the forefront of securing federal dollars and establishing policies to keep their cities safe, but we also have Black women who are a majority in the healthcare workforce and are placing their lives on the line taking care of the vulnerable, the elderly, and the sick, and these women are dying. We’re talking about essential workers who are working in low wage positions, oftentimes without adequate personal protection equipment, and who are fighting to keep themselves and their families safe. We have Black women on the front lines of this pandemic who are vulnerable in so many ways. We have leadership and we have labor, and that’s something that I’m looking at closely. I’m following these stories as they appear on a daily basis.

AE: Can we talk a little bit about, as you said, in labor and in leadership, but in practice as well? Are you creating work that is in response to COVID? Are you writing? Sculpting? Are you crafting work because of this shelter in place and as you pay attention, to the leadership and labor of Black women and our work as creative organizers, activists, and artivists as well?

LT: I’m reading a lot, I’m writing a lot. I haven’t started drawing or sculpting or doing any sort of physical, hand artwork with this information yet. What I am doing is a lot of creative things that I really didn’t allow myself the time to do—things that are fun, that give me joy. When I start delving into this research and really uncovering the ways in which Black women are both leading, working, and dying, that’s going to be a very serious project. Right now, I’m painting fabric. I’m creating plates and dishes and platters for when I can commune with my sisters and we can all share a meal together again. The kind of creative artwork is something that is feeding me emotionally and psychologically. The writing and research I am doing and really following the press will be a different project that I’ll approach in a much more serious way. Right now, I’m allowing my creative juices to really feed and sustain me and give me joy. But I am writing a lot about COVID.

“This is an interesting time in our history where collective grief coincides with collective joy because we need the joy to sustain us.”

AE: Let’s talk a little a bit about the collective grief and the collective joy that is unfolding for many people in the world. Some of us call this a time of pause, I’m calling it a time of reset. I’m very aware of the fact that many people are not able to pause and the level of privilege that some of us have—to be able to sit and consider and redesign and allow our practices to unfold differently. In terms of talking about grief and celebration in your work, you bring forward the women of The Montgomery Bus Boycott in addition to Rosa Parks. What are your thoughts on how we move through this history? Often the media or just our first instincts might take us to fear, but I find that if we allow ourselves to be with the deep grief and sadness of that, perhaps by creating ceremony and ritual around that history, the fear moves on because it’s actually the feelings of grief inside of us.

LT: There is a lot of fear that we won’t be safe when we leave our homes. There’s a lot of fear that when we go to the grocery store, we can contract this disease. There is also so much misinformation that is coming out of the White House right now, so there’s no national leadership around this. This is the first time I’ve experienced something so dire. This is also a global experience. Not all of us are experiencing it the same, but this is an interesting time in our history where collective grief coincides with collective joy because we need the joy to sustain us. At the same time, there is deep sadness for the lives that are lost. You have over 30 million folks, and I know those numbers are undercounted, who no longer have their livelihood so the global economic repercussions of this pandemic are hitting Black and brown communities especially hard. You also have a disproportionate amount of Black and brown folks who are infected, who are dying, and who have been living paycheck to paycheck and no longer have that income. They don’t know how they’re going to survive.

The pandemic has laid all that bare and visible. There’s no longer any way to dispute the inequities. We all know that in this country there’s this huge wage gap and we know that there is a lack of access for adequate and competent medical care in Black and Brown communities. We already knew this, but this pandemic has really laid those statistics bare for the whole world to see. We’re living in one of the richest countries in the world and yet we have communities that are financially impoverished and economically struggling.

AE: That’s right and that’s how it’s always been.

LT: Yes, yes it’s always been the way. We’ve had moments in the past where these kinds of discrepancies are really made visible. I think about Hurricane Katrina.

AE: With Hurricane Katrina, if there was any wool over your eyes, it was pulled away in terms of how this government actually honors and respects its people when it says, ” We are about our citizens, we are about the people who live here on this land.”

LT: This pandemic has been particularly devastating for artists and cultural workers as well. So many of the institutions and organizations that we rely on for our livelihood, as well as the collector class who sees their stock portfolios cut in half, are vanishing. Museums are closing, galleries closing, and a lot of those institutions and organizations are not going to come back. Collectors who are still acquiring, perhaps at a deep discount, but they’re looking at tried and true investments, so artists who are not famous are being ignored. There are whole swaths in the art economy that are being devastated right now.

Despite all of this very real suffering, for those of us who are healthy and surviving now, there are small moments of joy. For me, growing food for the first time, getting my hands in the soil, listening to the hummingbirds in my backyard, enjoying the company of my friends via Zoom, those are all things I hold near and dear because right now the specter of death is so close. I’m really treasuring what I have and having an attitude of gratitude and then helping others where I can.

Part 2 will be released on Friday May 15th, 2020 on YBCA’s Zine.

Ashara Ekundayo is an Independent Curator and Cultural Strategist. Her current multi-media platform #ArtistAsFirstResponder excavates, documents and archives the stories of artists whose creative practices save lives and heal communities. Learn more at www.Ashara.io or follow her on IG @blublakwomyn

Lead image: Audrey Belle Langford, from the Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott series, 2018, Graphite and conté pencil on paper, Courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery