Thu July 10th Open 11 AM–5 PM

How do we remember those who are not counted?

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

Cece Carpio paints people and places. Her work tells stories of immigration, ancestry, and resilience. She can often be found collaborating with her collective Trust Your Struggle, teaching, and traveling around the world in pursuit of the perfect wall.

YBCA Curatorial Project Manager Fiona Ball sat down with Carpio on April 13, 2020 to discuss her Actual Enumeration series, commissioned for the YBCA art and civic experience Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? This series features portraits of figures from various communities not currently represented in the 2020 Census.

Fiona Ball: Let’s start at the beginning. How did your artistic practice first develop?

Cece Carpio: I started drawing at a very young age. I was raised by my great grandmother and she is old school, she’s an OG. And she was illiterate. So when I would come home from school and explain some of the stuff about my day, I would draw pictures for her. It was kind of a household where everyone stopped by but for the most part it was me and her. So drawing also gave me something to do with her. Eventually as I got older folks started recognizing the skill that I have, which to me was just because that’s what I had spent so much of my time doing. I was fairly shy and still can be in certain situations and I think that being able to draw images allows me to express myself in a way that words can’t.

When I moved and migrated to the Bay Area, I loved just walking out on the street and being able to see the murals, this larger than life images. I was inspired by the art on the streets and eventually learned who those artists were and what the stories they were painting. As I got older I was able to collaborate with them and now I’m part of that community.I don’t really know if there’s an official start date on where I started having this professional practice per se. I feel it’s just something that I’ve always done. It is my way of exchanging ideas and having conversations with folks.

I think also being five feet tall, there is something amazing about being able to look at a big wall and be like “yeah I could that.”

FB: Coming to Your Census: Who Counts in America? features four of your pieces from the Actual Enumeration series. So could you tell us a little bit about how that series came to be and how you choose whose portraits you’ll be creating?

CC: When Martin [Strickland] approached me about this project, there was a part of me that was excited but another part of me that was kind of like, “What do I have to say about the census?” So I talked to different folks in my immediate community. Just having a conversation like, “So the census is coming up. What are your thoughts about it?” What was important for me for this series was to highlight folks that were partially counted or not counted at all.

I did a lot of research as far as how this census even started, the history of it to the point that I was able to get access to forms from back in the 1700s.

I was blown away by the fact that even now in 2020 this is still an issue that we’re dealing with in terms of who’s being counted, who’s counting, and what is this information being used for. I wanted to acknowledge this history through conversations with different folks. Some knew that the census can be very beneficial in our community, as a platform to say, “Yo, we are one of those tallies. We are a number.” But at the same time recognizing also how these census has been used against us and vulnerable communities.

CC: For the series, I wanted to represent certain types of communities with faces and figures that were semi-recognizable. Ilhan Omar for example, is Muslim and from Somalia. Having gone through what we’ve gone through politically here where Muslim individuals are being counted and banned from entering this country, but yet that very label is not accounted for while these populations are definitely vulnerable. Then the diaspora is not at all accounted for, which I think should be recognized as a different type of cultural experience for folks who have migrated in this country. They should be able to have access to certain resources accounted in the census.

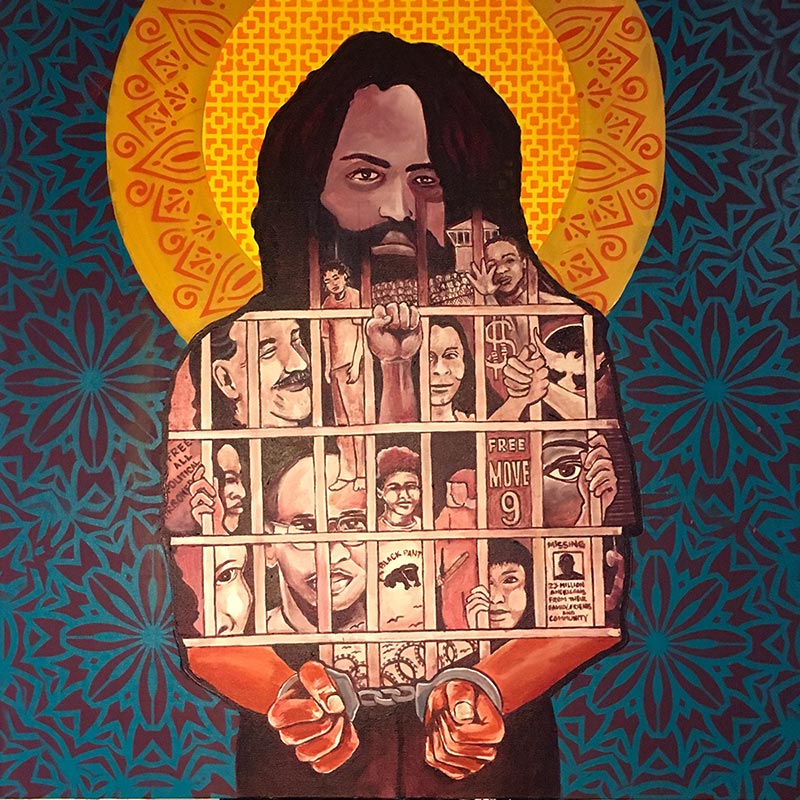

Another portrait is of Mumia Abu-Jamal. He’s been imprisoned for, I don’t even know how many years now, but his face has been in the media. I wanted to represent those experiencing incarceration, because the cenesu doesn’t even have space for them to fill out. These are folks who are pretty much erased by the census, but at the same time is the very population that is impacted by political institutions and the administration.

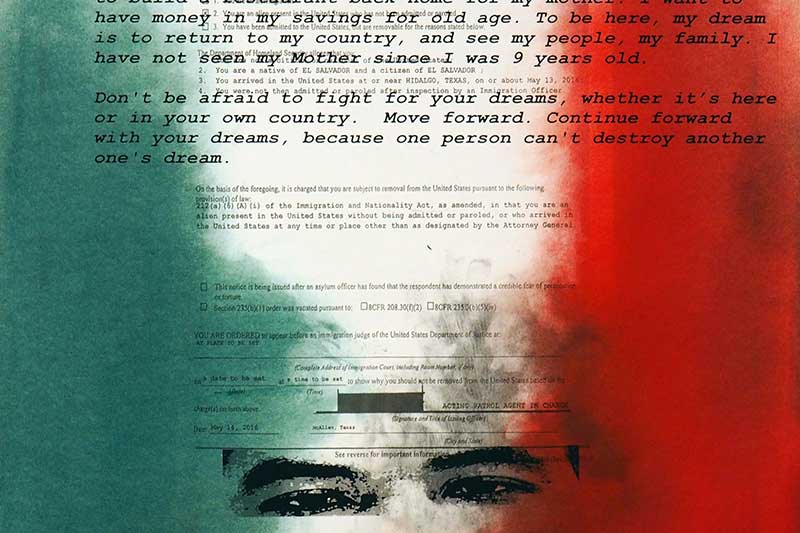

I also wanted to engage with the LGBTQ community and with the undocumented community. I had a harder time engaging with undocumented folks because people that I knew were doing work locally and many are still scared to put their information out there. There had been conversations about how the census was once used to target certain communities for deportation. But around this time, Victorina Morales, a very fierce, powerful woman, came out talking about her status and kind of the degradation that she dealt with working under this administration. She put herself out there. I thought I should recognize her.

Within each of the portraits there are a lot of the figures who are actual folks that I know and held conversations with while creating the series. It was my way of incorporating those voices given that it was our exchanges that allowed me to think more thoroughly about how to represent these populations.

FB: It’s like you’re showing your references, all the conversations and people necessary to arrive at the final painting.

CC: That’s also a big part of my practice, especially when I’m representing communities that I don’t necessarily belong to. I’ve never been to prison, I’m not undocumented. I consider myself a visual translator for communities, so it’s important for me to have conversations around the work. Then I’m representing them in a way that holds dignity and truth.

FB: Social distancing has been such a pivot for all of us at YBCA, because so much of the exhibition and the work within it is about visibility and all of a sudden we’re all put in isolation from one another, and forced to find new ways to still be with our community. Are you working on anything in response to this current moment to stay connected?

CC: I’m in my studio all the time, so I’ve actually been producing a massive amount of work. There are so many stories coming out that are very similar to the folks that I’m highlighting for Come to Your Census. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the vulnerable communities I work with are some of the most affected by the pandemic. This crisis points out the flaws in our political system–how we function and what and who is prioritized. So I’ve been painting a lot and showing my work on both social media. Mostly Instagram and Facebook and partnering with different organizations whose campaigns I feel are really important to highlight.

I feel like with everything that’s going on, if anything, it’s highlighting the communities that I paint. Just in terms of who is vulnerable and the different type of risks communities and individuals take as soon as they step out their door, or if they even have a door to step out of. It’s complimentary in terms of it’s a conversation. If I continued to create pieces for the Actual Enumeration series I would depict the same people that I’m advocating for and for who is impacted most by the current pandemic.

But I’m still grieving and mourning. The whole purpose of the work that I do is to have conversations and to gather people together to share our stories. That’s such a big part of my practice beyond the actual images produced. I’ve had to rethink what that means now. I’ve been doing zoom meetings and zoom parties and zoom all the time, and I can already tell I receive information differently, it’s an incomparable experience from being face to face.

My practice aims to provoke and motivate actions to feel like we’re all part of something bigger, that we’re a part of a community and that we can see our humanity within each other. It’s been difficult to adjust, but at the same time I’m now talking globally to different folks that I normally wouldn’t talk to on a regular basis.

FB: I think it’s good to admit that. I just said the other day to a friend, “I’m not as productive as I normally am and I feel guilty about it.” But we need to allow ourselves room for that. Your work is so much about creating visibility, so how do you see forms of visibility changing now?

CC: I’m continuously producing work and putting the images out in the world in the way I know how, with the tools that I have. Right now that’s Instagram and Facebook. But there are folks who have already taken my work and written letters to Congress with my images. There’s one now being sent to the governor trying to advocate for healthcare for all. I’m creating images around visibility and recognition that we all deserve.

Different organizations have used my images to promote the actions they’re doing like creating mutual aid campaigns to build awareness. I think one of my strengths is having a network of folks that are doing the work on the front line and that I could support it through my skills and tools. I hope I can visually attempt to tell their story or to put out the message that they want folks to know.

I’m fortunate enough that I have a backup, I have a lot of amazing social support from friends and family, but we all need to acknowledge that there are folks who don’t have that and don’t have that support. What I can do is to amplify those stories and those voices. We’re in a place where actually there’s so much more attention on the phone and on the computer screen, people are reading news all the time, so it’s a crucial time to tell these stories and hope that it will resonate with folks and activate them to take actions towards necessary change.

FB: How are you taking care of yourself right now? You’re making so much work and really instigating action through your art, is that what’s taking care of you or what is it that you are doing for yourself?

CC: Making work is my sanity. It allows me to turn my head away from the screens. This too shall pass and we will come out of it stronger and better, or at least that’s the hope. But as far as taking care of myself, as I said, I’m fortunate enough to have such an amazing community that we have each other’s back. I’m safe and healthy and mobile but folks are, just out of love, dropping off food on my doorstep, staying connected, and continuing to have conversations in terms of what it is that we need now.

I’m definitely one of the more fortunate and lucky ones. I’m producing work as I want to be able to support the campaigns but my studio is also my place of sanctuary and sanity, because painting allows me to get the anxiety out.

I feel like I’m busier than normal now, but I think rest and just self reflections are still very important, especially at this time. It’s the time that we have to be able to really embrace it. The work will not stop even when all of it is done. Whatever that might look like as things have already changed and will continuously change. I think the trick is making sure things change in a the direction where it serves us all.