Fri February 27th Open 10 AM–5 PM

A World of Many Fires: the Decade Known as 2020

I was fortunate enough to become YBCA’s ArtTable Fellow in June, 2020. ArtTable is an organization dedicated to the advancement of women in leadership roles in the visual arts, and recently celebrated its 40th anniversary. I recently graduated from New York University with a bachelor’s degree in art history and applied to ArtTable’s fellowship program as an opportunity to understand the world of art institutions further while gaining professional experience. I was born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and San Francisco seemed like a world far from my own with an exciting art scene I was eager to explore.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everyone’s plans, as institutions were shut down and everyone was encouraged to shelter-in-place. Now, I am completing the fellowship from my home in Puerto Rico, working remotely for the YBCA team. As part of my fellowship projects, I had the opportunity to virtually sit down with artist Jerome Reyes and YBCA Associate Director of Public Life Martin Strickland, to learn more about Jerome’s life, work, and thoughts about this year’s historic events.

Jerome Reyes (b. 1983) is an artist, researcher, and educator who works between Seoul, Korea and San Francisco, CA. His work Pharos (Anonymous) (2012), is part of YBCA’s exhibition Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?, which was required to transition online because of the pandemic. Although we possess the same last name, we are not related; Jerome actively works within his community in his native San Francisco. He is Artist Liaison and faculty at Stanford University’s Institute for Diversity in the Arts, teaching courses and designing partnerships with artists, curators, scholars, and organizations. Reyes is also a Researcher, at Asia and Migration, Asia Culture Institute, in Gwangju, Korea. He is a long-term collaborator of the South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN) in downtown San Francisco, and is an advisory board member of the nonprofit media and culture organization, Define American. In 2016, Jerome was invited to be an Artist-In-Residence at YBCA and since then has become a long time collaborator with the institution. Our conversation was held on July 30, 2020 via Google Hangouts and has been edited for clarity.

Carola Reyes Benítez is a recent graduate from NYU’s College of Arts and Sciences. Born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, she embarked to New York City in 2016 to pursue studies in Art History and Business Studies. During her four years in New York, she has had various experiences in the art world, including internships at The Whitney Museum of American Art, Sotheby’s, and Salon 94 Gallery in NYC. Her academic interests include international contemporary art and design, specifically that of the Americas. Her most recent experience as the 2020 ArtTable Fellow for the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, held online, involved creating a research portfolio analyzing trends in online exhibition spaces for the advancement of art institutions post-COVID-19.

Carola Reyes: So how are you today, Jerome?

Jerome Reyes: I’m alive in this decade known as 2020.

CR: Thankfully so am I. So I’d like to begin by asking you about the Come to Your Census exhibition. Why do you believe you were included in this exhibition, and how does your piece resonate with other works presented?

JR: The exhibition is one of many YBCA curatorial projects I’ve been a part of that allow me to engage many localities and legacies of the Bay Area, to unfold this complex point of view. The Census show could have happened four years ago. I think this work that I did with Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas, who is also a YBCA 100 honoree, the founder of Define American, and someone who also grew up in the Bay Area, is a huge theme for these loaded political works. The show was exciting because it features a lot of great Bay Area artists from many different identity formations and geographic locations of the East Bay, San Francisco, and the larger Bay Area as an enduring idea.

I wanted to make this backdrop of a supporting, ominous artwork. The quote that I have from Jose Antonio Vargas is this enigmatic line, something that he said to me about nine years ago. In an unsaid way, it’s the precursor for the Abeyance billboard that’s been up at Yerba Buena since 2017. It’s this lovely way of retrospectively looking at the voice of someone who many would say is the most highly profiled undocumented person in this country. So, that type of complexity, that type of robust weight of subject matter, is something I’ve been invested in, and which YBCA has been an amazing supporter of for more than a decade.

For me, the Census exhibition is showing something very immediate, very in the moment. But, there are subtle differences between the contemporary, of the current, of today, and then of the past decade of politics. This show, for me, winded up all of those durations of time to where we joke, or at least I do, about the decade in this conversation known as 2020. You can equally say it’s a world of many fires.

The Census is a way to show those many fires that don’t just occupy space, but also occupy time. So my piece was and still is able to kind of work through all of that landscape. You can still see it with all the smoke and fire more or less.

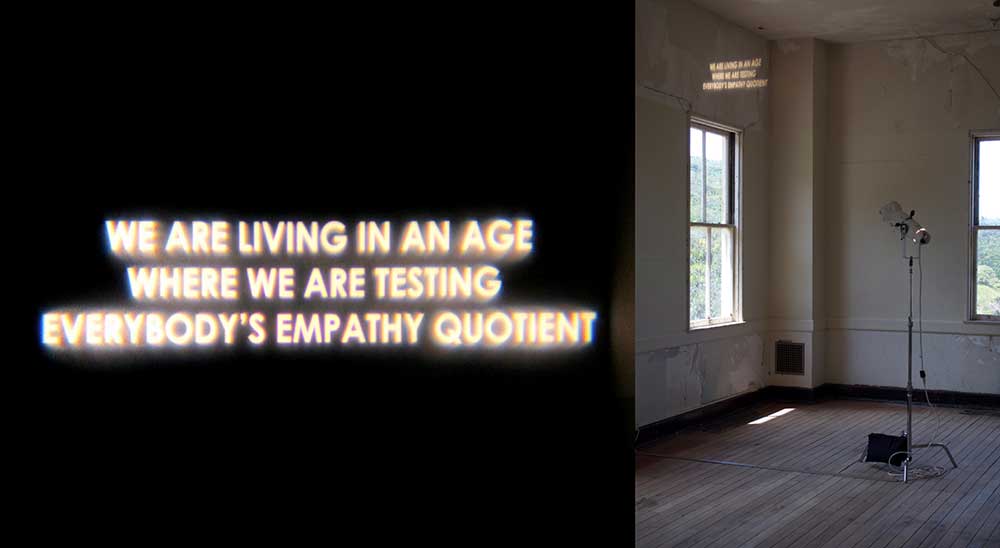

CR: The light cutting through the smoke and fire you’re referring to, is that left by Pharos (Anonymous)? Could you speak a little bit about the piece, how it came to be, and why you think the phrase it contains is relevant right now?

JR: The premise of Come to Your Census takes multiple barometers of this country, with the stakes and the symbolism of the Bay Area, for so many different people who live here and who moved across the United States. The quote reads, We are living in an age where we are testing everybody’s empathy quotient. It was actually made during a time where Jose was looking at social media as a way to gauge everyone’s humanity or how they feel living with one another. I think over time, the text has become much more rich, fraught, even more complicated years later.

It was done during a residency I had at the Headlands Center for the Arts, in Marin, California, which is on this Cold War site, a decommissioned military site formerly armed with the Nike missile base. I was there for a year, where I had worked on this piece. The sculptural form is this inverted stage light, a gobo projection unit, it projects a pretty beautiful light with this light bulb and lens.

If you look at it, the projected lettering resembles a steaming flame on the surface it’s projected on. It sets up the scenography, if you want to get technical, for theatrical moments where it lights up on stage. So it hints to portraiture, it hints to theatrical blocking. There are all these tonalities where the installation itself has this futuristic looking searchlight in a steel and white palette. It looks as if it were part of this amazing context of the militaristic backstory of the Marin Headlands. Also, there’s different references coming into my work where at the time I have all these socio-political and historical influences. I was able to show this body of work with L.A. artist Daniel Joseph Martinez, who is a big conceptual influence in the United States, and also for many international artists. Martinez influenced this text piece because I was also looking at science fiction, even looking at comic books.

The Editor-in-Chief of Marvel at that time was Axel Alonso, who grew up in San Francisco. He decided to move the Marvel comics X-Men to the Bay Area in San Francisco in this gesture of what the Bay Area means for different demographics of people in the United States. It was so fun and interesting because all the X-Men superheroes were going to Giants games, they’ were enjoying neighborhoods of San Francisco and I was like, “Where’s their hidden base?” It was the Marin Headlands. I showed this to the Headlands Center for the Arts’s staff, they were like, “Oh my God, how do we get in contact with Marvel Comics!?”

But really, a lot of the aesthetics, the research and the conceptual framework of the piece, are all coming from those moments where it’s this potent chemistry of pop culture, real life culture, the history of these militarized United States sites, it’s people of color. That type of asymmetrical weight I always try to have in my work. So in a lot of ways, the YBCA Abeyance billboard, which is up now, a lot of the thinking has come through that singular light projection piece. So it’s a wonderful moment for me to speak of the preamble or the predecessor to a billboard so ingrained at Yerba Buena now, which is this singular light text that is the backdrop of an Census exhibition.

Martin emphatically said the show was 72% done, and I imagine inside this exhibition the piece can be physically positioned anywhere. The text can be scaled, it can be really tiny and intimate. It can be huge and become this gigantic proclamation. It’s the flexibility and dexterity of these moments and these texts, which is why I wanted this specific piece in the show, because it’s made to support everyone else.

CR: Not only do you have a piece inside YBCA, but you have one outside as well. Could you speak about Abeyance, the billboard project outside of the YBCA building, and how you think that piece actively resonates within your community in San Francisco?

JR: The billboard is a public art project commissioned by YBCA and this amazing visual arts team, where Martin is the last bastion of that institutional memory. So that was a dream piece in a lot of ways because there’s so many ways to formally enter it. It was offered to me behind the scenes by Katya Min, who was the project director, and Lucía Sanromán, formally the Director of Visual Arts at YBCA and now the Director of Laboratorio Arte Alameda in Mexico City.

I actually have beautiful family memories of this area. When SFMOMA opened across the street in the 1990s, my mother appeared looking through the galleries on the clip for Channel 7 ABC. My father is also in the San Francisco Chronicle cover photo standing in the stairs literally overlooking the grand lobby. The very first exhibition I went to inside the Yerba Buena galleries was the Star Wars props exhibition. I was like ten and was like, “Oh wow, this place is big. It’s built like a cruise ship.” It’s actually designed like a cruise ship, the architecture inside. I was overeducated in just so much institutional history where it became an advantage that I wanted to bring into this public art commission.

So the first thing I thought of actually was Abeyance’s three quotes that are from four different people in proximity to the Martin Luther King Jr Waterfall, intertwining different decades and formations of San Francisco as a global city, with a photographic backdrop of the Pacific Ocean at Ocean Beach, which is literally the edge of San Francisco. It’s literally the edge of the country, and for some people, it’s the edge of the world. It shifts by the second much like the politics that the country is going through at the moment. The top quote is Jose Antonio Vargas with his mother as she sends him to the United States, and the last thing she’s ever said to him in person. The middle quote is poetry by the highly celebrated Al Robles, a poet and activist from the International Hotel Saga, among many organizing legacies of San Francisco. The bottom is the Olympic diver and double gold medalist Victoria Manalo Draves, who was just honored globally in a Google doodle.

Honestly, just having one of these figures would have been a complete statement, but I pursued the weight and endless combinations that was possible in a tapestry like this. Moreover, Daniel Joseph Martinez proposed a stunning and controversial unrealized public art commission in 1992, a block away literally at the Moscone Center. I wanted to re-engage his work conceptually 25 years later with my own, as an artist I am historically entwined with the same local context he addressed.

Something that’s never been said before either as we talk about YBCA’s institutional memory, is the conceptual family of exhibitions, if you will, led by Lucía. There’s this wonderful piece by Tania Bruguera on the other side of YBCA that is an orange interchangeable façade of letters . I like to think my text has been so versatile, and supple, and emotionally open to where it’s been able to handle the moments that have happened the last couple of years, while the Bruguera’s piece is incredibly mobile, and current (you can change the text whenever you want). It talks about local issues, heavy national conversations, even international news. It’s able to be reconfigured literally at any moment, or stay up for a couple weeks. I think the dialogue between those two billboards physically outside YBCA in a way has been this incredible gauge of now, in the news, and a pulse of many different timelines and localities that again, my billboard was made to be flexible for that. I’ve been lucky enough that it keeps getting extended because of YBCA having different things going on inside, or having different shows, and now the pandemic. Luckily Abeyance has become more encompassing conceptually to world events in the same way the Census light text has been more meaningful over time.

Martin Strickland: It was really Katya and Lucía coming together and really thinking that we were bringing in Tania, who has no history specifically in the Bay Area, to be able to show work paired with Jerome, who has such deep rooted history in the Bay Area. I think that those two works, as you’re saying, the way with the lettering and the messaging can talk, really speak to one another as well.

JR: Furthermore, we didn’t mention pioneering artist Suzanne Lacy, who for a long time was such a fixture in the Bay Area and came back for a retrospective co-organized by Lucía, Rudolf Frieling, Curator of Media Arts at SFMOMA, and Dominic Willsdon, formerly of SFMOMA, and now is the Executive Director of the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. I locate Abeyance and my larger work across these longer timelines within that legacy of contemporary art and socially engaged practices, in addition to all these other themes that we’ve been discussing in this conversation.

CR: What does it mean to you to have a piece outside of the museum, in a time where no one can really walk into a museum?

JR: I love that question because the billboard was mounted in response to the site, and the incredibly expansive and shifting demographics of who’s in the park. It’s next to the biggest convention center in the city. You have seniors, immigrants, and elderly playing chess. You have people taking their lunch and people spending their afternoons in the gardens. You have families running through, kids playing after school. Also, you have people early in the morning doing Tai Chi and the people walking to the park on dates. So you have all these international, intergenerational audiences.

I realize the billboard is now on a date site for Yerba Buena. I will also say it’s become a date site for teenagers, including some of the students I teach. [laughs] They’ll tell me, “Oh I brought this person to the billboard, and I impressed them saying what it’s about.” I was like, “I’ve hood made it in that way!” [laughs]

MS: It is also featured on YouTube’s “Best Things To Do in San Francisco” video. All of these vloggers, that’s all they do is travel the world, they put all of these spliced images together with creative commons music, where it’s like a drone going really fast and then really slow. “And then this downtown oasis to Yerba Buena Gardens.”

JR: That’s awesome. As really serious and moving as a project it can be given the context, it also conveys a complexity of victory. Draves’s double gold medals, Al Robles and that organizing community opened a new International Hotel in 2005, and Vargas in dialogue with his mother, I predict he will eventually will go back and see her someday. There’s this again the irreducibility of these epic accounts, and I think Carola, to answer your question, I love that very few can see the billboard in person, but it’s still online and maintains its impact.

Speaking of fires, there’s a literal California fire that happened several months ago, which permanently changed the color of the billboard to a bronzed sky where the textual readings, ambiance, and tonality now gracefully shifted and altered. As the world has become more complicated, I’m fortunate the billboard is just as magical for different people who see it for the first time. Again, to what Martin was saying and your wonderful questions, the site is incredibly loaded to where it’ll never run out of conceptual gas in that way.

CR: You’ve mentioned Lucía and Katya quite a bit already, could you speak about the relationships you’ve created while at YBCA that have been meaningful, or played an influential role in your practice? I would also like to ask about artists and curators that you admire that have shaped your practice in the past few years.

JR: Great, so I’ll take YBCA first. So that team is of course Lucía, Martin, Katya and then Susie Kantor, now at the UC Davis Museum who is another SF native, and one of the biggest Giants baseball fans that I’ve ever seen. Dorothy Dávila got up at 4:00am for this billboard, bless her soul, and sent me the installation photo with the crew. I was so excited shouting “Oh I get to see it mounted!” and it was like seven in the morning and she’s like, “Jerome, it’s already up.” It’s a beautiful thing about the institution, I always say, it’s a small staff with a big building.

I have these fun personal relationships that point to my ongoing time in Korea actually designing the billboard in 2016. I was researching it in residency at the Seoul Museum right after I had received the 2016 YBCA residency, and was already thinking of a public program I wanted alongside Vargas in live conversation.

That night became thrilling because it was different communities that I traversed through, as Stanford faculty, my Stanford students, the Institute for Diversity of the Arts. The YBCA talk with Vargas also examined his book Dear America, and we went at each other in this beautiful way in that we finally had time together. I met him several years earlier making the light piece that is now in the Census show, but we never actually got to sit down and talk. That’s the very first real conversation we’ve ever had, which is extraordinary.

MS: Yeah it was an incredible evening, but I still can’t believe that was really the first time that y’all ever had the real face-to-face talk.

JR: Something very serious to mention, given the concept of this work, we had to be ready if ICE was going to show up. So there were backup plans if they were going to get him on stage. I had heard some people that were also very skeptical about the nature of the talk because Yerba Buena has this contentious relationship with certain communities because of the way it displaced thousands in its formation in the 1990s. I had to plan for that as well.

There were leading activists from the 1968 movements at CAL and Berkeley in attendance, so a lot of people supporting me, but also a lot of uncertainty in the room. So you have to be on and locked in, in terms of having this public presentation of someone very high profile and very controversial, while also questioning if ICE agents are going to barge in at any moment, while being focused because your students and friends are in the room, and because there’s a few cantankerous haters in the room. [laughs] I think Yerba Buena gave me this moment of support forever. I feel like I can walk away from that moment knowing that every check mark was marked, and all those supporters were there. Those are the moments you live for, again with the irreducibility of this work that talks about the local, the global, the historic, the current, all those in tandem gracefully with humor, which is what I want my work to be.

So, extending to your second question Carola, my conceptual influences are Daniel Joseph Martinez and my close collaborator of 15 years in Seoul, Korea, the artist researcher and professor tammy ko Robinson who I honor in my upcoming book chapter that spans twenty years of my solo and collaborative work “No Matter Where We Move We Look at the Same Moon, A Half-Century between the Pacific and Stars,” for Public Space/Contested Space (Routledge, forthcoming). This chapter also honors this same two decades working with one of the founders of the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University, Daniel Phil Gonzales. So it’s claiming this long game practice that is inherently multidisciplinary, multigenerational, globally reaching, and hyper-local.

Other people include: cultural practitioner William Cordova who had a solo exhibition at Yerba Buena in 2012 and who I had the honor of collaborating with on a film/installation for the Prospect 3 Biennale in New Orleans, among many other collaborative projects we’ve done over close to a decade, and Julio Cesar Morales, a great friend for more than 15 years, co-teacher/artist/curator/dj, who was a former curator at YBCA and very much a supporter of the early Vargas work. Looking at these long friendships, I’m never in a rush, and often this reflects in how this work takes several years to complete because I believe the world will always be on fire in this way.

CR: Definitely. Speaking of the world being on fire, we’re all separate right now in our respective homes sheltering-in-place because of the pandemic, and unable to socialize. Your work focuses so heavily on relationships. I wanted to touch on how you are maintaining your various friendships within your practice during times you were encouraged to stay away from others.

JR: I lived in Korea in 2015 when MERS was happening. So I was already accustomed to what an epidemic can do to a huge urban metropolis. I had masks, I had sanitizer, I knew how to navigate the vast city. I was actually very calm when the United States locked down more or less.

I’d already been working on my project for the 2020 Yokohama Triennale with other people who have influenced me Looking back, I was faculty of the San Francisco Art Institute/SFAI in 2005, I was part of this once in a lifetime administration which had curators Okwui Enwezor as Dean and Hou Hanru as Director of Exhibitions and Public Programs to where I was able to have their worldly guidance in my early 20s, while combining it with this long multi-pronged legacy of the Bay Area, and artists around the country. I was able to take that chemistry and create this alchemy of having access to the rest of the world at multiple scales where I was looking at different localized research practices. I was able to play with compelling,large historical and political trajectories. I was given a blinding, luminous green light in a lot of ways.

So, the renowned artists-in-residence I met 15 years ago at SFAI, Raqs Media Collective, are the artistic directors of Yokohama, in a beautiful way I have this personal revisiting almost 15 years later, to where friends are now also part of the Triennale’s curatorial ensemble, who also are my generation. I worked very closely with Hong Kong based writer and curator Michelle Wong, and the team extended, which is writer and curator Kabelo Malatsie, based in Johannesburg, South Africa, and Lantian Xie, an artist who travels and works between Dubai and Hong Kong. The three of them are around my age, so it’s basically a dream where you’re working on a triennale project with your friends and colleagues, and led by Raqs.

What’s really beautiful about this online work is my contact friends daily. We text each other memes, food photos, keeping each other energized to where the different public artworks I’ve made for the Triennale are directly influenced by the YBCA billboard, and they have studied the YBCA billboard to make this commissioned work for the Triennale. The title is also called Abeyance like the Yerba Buena Billboard, but the quotation now is, Abeyance (We Gon Be Alright), which is the title of Jeff Chang’s book that he published in 2016. Jeff is a mentor and former Stanford co-teacher, writer and current Vice President of Narrative at Race Forward. Jeff Chang has a practice that I share with him, that we have a practice of citation, so it’s fitting to also point back to his work through this public artwork.

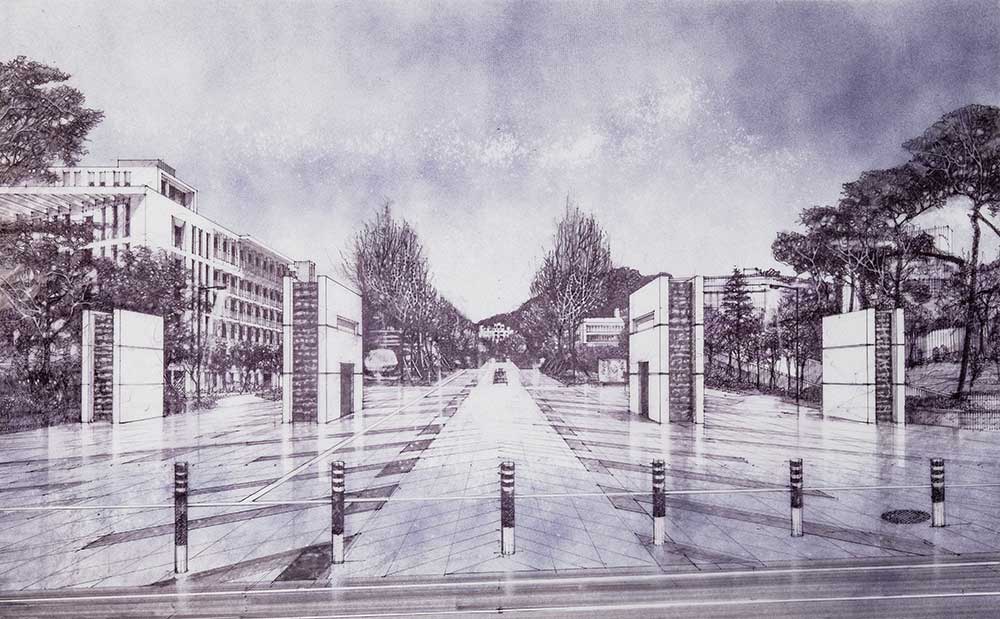

I also have a parallel series of architectural drawings of global organizing sites, the horizon toward which we move always recedes before us. The quote comes from the last passage in Chang’s same book. I wanted to take the whole spectrum of realities of organizing and protest to where we meditate on how people are imperfect, whether it’s concerning different leaders, groups, or disagreements. The tone of Chang’s quote takes a realistic optimism: that we will be alright, despite having to go through yet another wave of injustices. Instead of working with quotation it’s continuing this practice of citation through locales.

So with the Triennale team, and more so my longer work in Korea, I work in a way where everyone is half a day into the future. My meetings in San Francisco at night are for everyone in Asia, to where they’re telling me what’s happening in the near future. I have to think half a day ahead all the time in a wonderful way. It’s permanently changed the way I look at time, to where I don’t fully feel here. I think that’s what stabilized me to where again, I feel I’m with everyone looking at different situations in the world, to where I don’t really miss anyone because I’m always in contact with them in some form. Even if I’m not seeing them on Skype, or on the phone, or texting, which is what we’re limited to, I’m thinking about their ideas a lot, so I’m never that far away. It’s like being at the campfire with everyone, looking across and seeing their silhouette.

CR: How has your relationship with art and activism changed if at all during the course of this tumultuous year?

JR: The project for Yokohama, as of this moment, there’s 13 different episodos happening across the world. It’s become this exquisite framework in mega exhibitions and curatorial practice, given museum exhibitions and the type of viewership, I think is fundamentally altered. I don’t even know if we’re going to have crowds for the next several years.

The moment where statues are being pulled down, Black Lives Matter is being painted on streets, that’s very key. It’s painted directly so you can see it vertically from above. So it’s fundamentally different to look at the way that cities are viewed, in the way that it’s across from a like the White House or a different building. The realization of these tactics and the speed of this velocity of change is something where I think the “decade of 2020” is going to be studied for years to come.

In terms of this confluence of public culture, of organizing, of online organizing, the way that Instagram has become really this main tool and weapon of so many people that traverse activist circles, artist circles, cultural production, politics. Again, the fun that I had working with Jose is now where we just try to come up with the craziest ideas that work. At the end of the day, it’s like, “What’s going to work now?”

I had this great conversation with a friend and we were thinking of people who have been saying this for a long time for many years within museums, within institutions, about what type of equity and various forms of systemic change need to happen. The statements that have been released on Black Lives Matter from institutions, some are more explicit, some are wishy washy, some won’t say Black Lives Matter. But there’s this moment of caution to where there’s optics and there’s people being very opportune to say what they align with. Are they going to be doing this real tough work even next month? Are they going to be doing this next year? In our conversation, I told my friend, “I’m on the Grace Lee Boggs timeline. Can you get to 100 years of life with this work? Can you go that long? Can your friendships outlast even these movements? Can your work outlast institutions to where no matter where you are, you’re bringing that with you because institutions change, and administrations change. That’s just the truth of how these systems work.”

I would hope that, as excited as people are, they need to be reminded of, and as harsh as it sounds, you are not an activist after reading one book. That’s not how this works. People have put years and decades into this, and have been saying the same shit, and working on it, and they’re not celebrated. They don’t care. They know how long this takes and exhausting this is. The right and conservatives, they are just as smart as us, they are just as equipped. That’s one thing that I think that people need to realize. In recent years, they beat the left, they won. You look at different countries around the world, and see that this moment is really about what constitutes the notions of “the long game.” I would ask my students, my coworkers, I ask that of myself, how do you maintain stamina and endurance to where you give yourself a fighting chance, given that the last several decades around the world and especially the United States have been so tenuous and so fragile?

I hope that’s reflected in the artistic work that I make because those are the things I’m thinking about. It’s why I have these citations from We Gon Be Alright which was written in 2016, who could anticipate that this year is even crazier than 2016. I can imagine election day 2020, which the Census leads to in a lot of ways, will feel like one year, that full day itself. I don’t know if I can go online. I feel like by the time it hits 9pm, 10pm, I think everyone’s going to be so exhausted.

MS: The day that we’re doing this interview is the first day that Trump publicly talked about postponing an election, right? Whether that comes into fruition or not is not the point of what we’re talking about, but it is sort of significant to say that thinking about time, and then thinking about specific years, specific days within those years, and really sort of seeing the extrapolation of all of this. It’s definitely all tied up together in a way.

JR: Because this year has been so extraordinary in that one week there were attacks on Asian Americans, and the next week George Floyd dies and then all the uprisings, and how symbolically that has traveled throughout the world in this truly amazing way across language and image, across countries, across different demographics. Now we’re approaching August. What’s going to happen this month? Exhaustion is not a big enough word to what human beings are going through this year. I mean Australia was on fire, Kobe Bryant died. We’re just getting past halfway. Who knows what’s going to happen in this sad, hilarious, terrifying way, but you kind of know it will, and that’s what this way of working is made for.

CR: Going back to what you said about art outliving institutions, I wanted to end on just asking what you think would be the future of art institutions, and the rest of the year really. What do you think lies ahead?

JR: World still on fire everyone, the decade known as 2020 LOL. I think online lecture series are going to become the repository for some of the most important educational discussions that we’re going to have for at least the next year and a half. It’s heartbreaking because especially for children going to school, hugging, shaking hands, being close as siblings, as friends, all of that is now fundamentally altered, because you can’t do that. I look at generations of people not being able to hug their grandparents, parents, to high five each other in sports games, to go with crowds, to be at parks or clubs in the same way, etc. It has fundamentally altered the way we physically interact with each other.

So what’s going to happen even if there’s a vaccine? What’s the protocol for everyone to get it? How much is that going to cost? What’s going to be offered? All of that, that’s probably another six months. I say this having lived in Seoul which is infrastructurally put together way better than the United States.

Carola, I’m sure you have a different peculiar experience as well where you’re at now, where institutions of culture and of public history are figuring what to do moving forward. The potential of what they do with extremely intelligent, over-educated staff, directors, and curators is going to guide us on what to think about because public education, public knowledge, and contemporary art is now fundamentally altered to where it’s really going to rely on sharing information and studying online together, and less on viewing physical exhibitions, but more so working with each other as colleagues and trusting each other. I think that is super exciting. I mean if anything, I just think New Years 2021 might be one of the biggest celebrations on the planet because it’s just like, “Okay, 2020 is done!” Invest in fireworks because that day may be the loudest day on the planet.[laughs] I’m half joking and I’m half not because I think this is the moment of “We made it.” I think institutions with these amazing leaders and artists, and a lot of people in it together are figuring out, “Okay, what’s the best can we make of it?” because we also have to live through this. So I’m committed to this really complex work that has all these different references, and citations, and pointing to other artists, and curators and thinkers with a huge legacy of success that I believe we can pull from.

The work that I made are these moments where we get to slow down and reflect on it, but then the bigger framing is this ongoing way of living through again, a world of many fires.