Thu July 3rd Open 11 AM–5 PM

Subverting Visibility: Arleene Correa Valencia & Ana Teresa Fernandez in Conversation, Part 1

Building Collaboration

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 U.S. Census.

Featured in YBCA’s art and civic experience Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?, SOMOS VISIBLES—commissioned by Art+Action as part it it’s COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign, with the generous support of Levi’s—is a collaborative artwork by artists Arleene Correa Valencia and Ana Teresa Fernández. This ongoing project takes a political stance on visibility through the use of high visibility ready-to-wear safety gear present throughout many labor industries.

YBCA Curatorial Project Manager Fiona Ball sat down with Correa Valencia and Fernández, on April 1, 2020 to discuss the history of their collaboration, the importance of visibility, and how they are caring for themselves in uncertain times.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

Fiona Ball: How did you two first meet and when did you start collaborating?

Arleene Correa Valencia: We first met in 2017 at the Anderson Ranch residency in Aspen.

Ana Teresa Fernández: Anderson Ranch is a super, super hoity-toity kind of residency artist program for, I would say, a little bit higher end demographic, because it is in Aspen. So you have very quaffed, intense, eight hours a day workshops. So they approached me wanting to teach a more conceptual painting working. How many artists were there, Arleene? 12, you would say? 12, 15?

ACV: Yeah, I think 12 to 15.

Courtesy of the artists.

ATF: Something like that, and the demographic was, I would say, 90% were white and elderly or white, people that have more access, their kids, or adults themselves that wanted to take painting classes. Then I had two students, who really stood out for me from that class. One was Eileen and then the other was Arleene. Eileen is a Pakistani student from New York who was in fashion, at the Fashion Institute in New York or Parsons, and Arleene was from CCA [California College of the Arts]. I was just blown away by these two women. I loved that there were two women.

Then I heard Arleene’s background, and what she was doing. What she was working on aligned so much with the class, which was to really kind of investigate more of a conceptual background around identity and social politics.Her work touches upon undocumented migrants working in the fields, and her community up in North Marin and Napa. But at the time, she was only working, I remember, with pigments that she would mix from the soil, right?

ACV: So I was going out hiking in Napa and Santa Rosa and collecting the pigments from the ground, and then I was making my own paint. I was very stubborn about, “I’m only using these colors.” In a matter of a week, Ana just turns me around and was putting green in my painting. I remember just feeling like, “Oh my god, I’m going to kill her.”

ATF: Yeah, she was like, “Don’t fucking touch my painting.” But you have to understand that they were beautiful. They were super beautiful, but they were burnt sienna and burnt umber colors. The thing about the work is that the skin tone wasn’t going to come forward if everything was in that tone and color. I was like, “No, you really got to use the colors from the images. They’re really impactful and they tell so much of the story.” Arleene was just growling at me the entire time like, “Don’t touch my painting.”

ACV: But it was the greatest thing that could have ever happened to me ever in life, and it was just so funny the way that things worked out. I initially wanted to take a different painting workshop, but I got a scholarship to do the one with Ana. I was really grateful for that and really happy. Of course, then there was the resistance of, “Okay, this lady is touching my painting. She doesn’t know me. She doesn’t know my experience. What’s happening here?”

But then I left completely different, and even though it was such a short period of time, it really changed my entire practice and the way that I viewed color. Then my painting started evolving and changing, and they became so much more colorful. Then Ana and I kept in touch just through Instagram and through social media. We were just staying in touch, and it wasn’t until, what was it? Last year, Ana, that you started your project?

ATF: Even before last year, I remember you contacting me a couple times, and you’re like, “Listen, I’m not jiving with some of the teachers here at CCA Do you want to come and look at my stuff?” So I went to your studio a couple times, and we were discussing your work. That’s when you were working on the dark field paintings.

The dark imagery that you were using [to represent] the workers at night was so intense. So we were having these conversations about the materiality of the workers, and especially the head lamps and how they mimic some of the imagery that she was using of some of the Mayan and Aztec gods of air and fire which have the headdresses that look very similar to the head lamps that they wear at night.

I was, of course, getting super inspired by just everything that she was working on. It just felt like every time we would meet, we would have these very intense, explosive conversations and really digest or dig up the ideas that she was working with. It just also became really informative for me.

Then Arleene, I will never forget, because we were socially in touch through Instagram, she had this amazing post, which really just… It’s those moments I always talk about in my lectures where they just hit your gut, and you just experience a side of reality that you’re not in touch with, and you check yourself.

ACV: A lot of what I was thinking about at the time after meeting Ana is there’s all these artists that are up and coming and establishing themselves around the migrant narrative–talking about migration, what it means to be undocumented, and what it means to be a minority and person of color. I was really inspired by all that, but at the same time, I felt like there was this need to speak for others.

On Hyperallergic, Artforum, and all these art-related magazines I was seeing [articles referring to] silent people or the voiceless. Like, “So-and-so is speaking for the people that are hiding in the shadows,” so it’s making work to give a voice to this person, or these people, or this community. Inside me, I just felt so frustrated. I even went to my dad, and I was like, “Dad, I hate these people.” It’s not that they don’t have a connection to being undocumented, but it’s that it’s different when it’s actually your experience versus when it’s a second and third-hand experience, right?

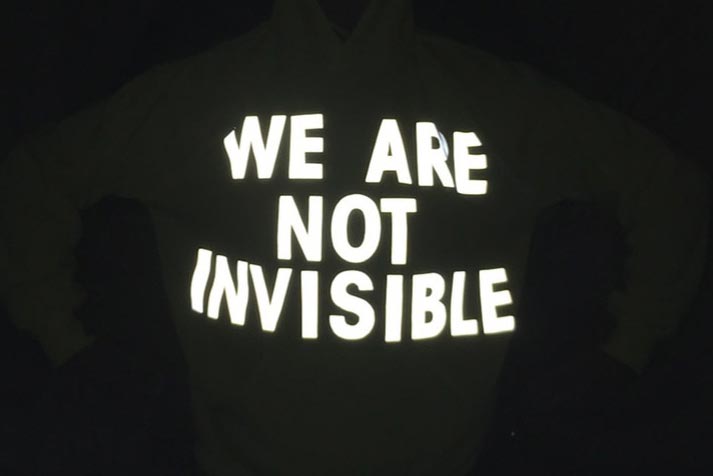

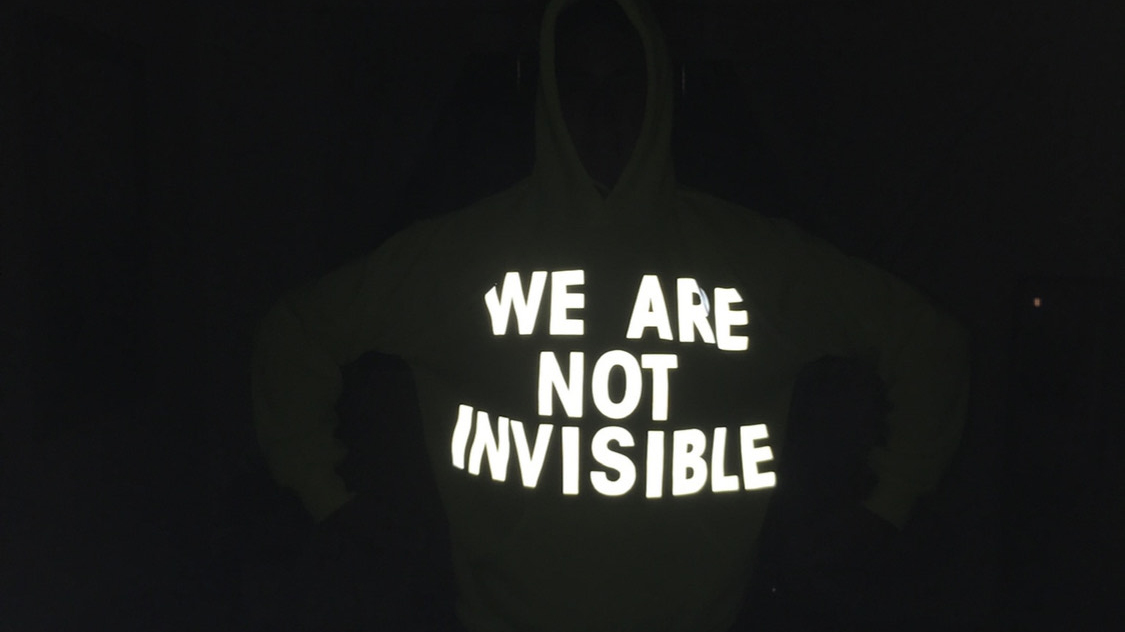

So there’s a lot of holes that I was able to see in other people’s works, because I understood what they were talking about, and they weren’t able to translate it right, or not the right way, but in a truthful way. I just got really angry one day and shot off on Instagram. I don’t even remember what I really said, but I said something along the lines of we are not invisible. We are not voiceless. We are not all these things that you keep perpetuating by telling our narrative, but we do have a voice. We are here. We are present, and we want to be heard. We just don’t have the right platforms to do it or something like that, right?

ATF: When I saw the post I was like, “Oh damn, truth. Truth to power.” So I was like, “Well, if part of what I try to do is illuminate sectors and actually provide voices through this visual platform, I thought why don’t I start here? Why don’t I actually work with someone that I do know? So Arleene gave me this idea. I had been working a lot with Creativity Explored, and a lot of the women there that actually don’t have voices, they’re mute, so they literally don’t have a voice. A lot of them knit and create these beautiful, textile pieces.

So I picked up a needle and started creating these drawings with thread and yarn. I taught myself how to do text pieces on fabric. Then when I saw Arleene’s post, I was like, “Why don’t I translate this? Why don’t I actually create the voice of the person so they can actually speak it and wear their voice?”

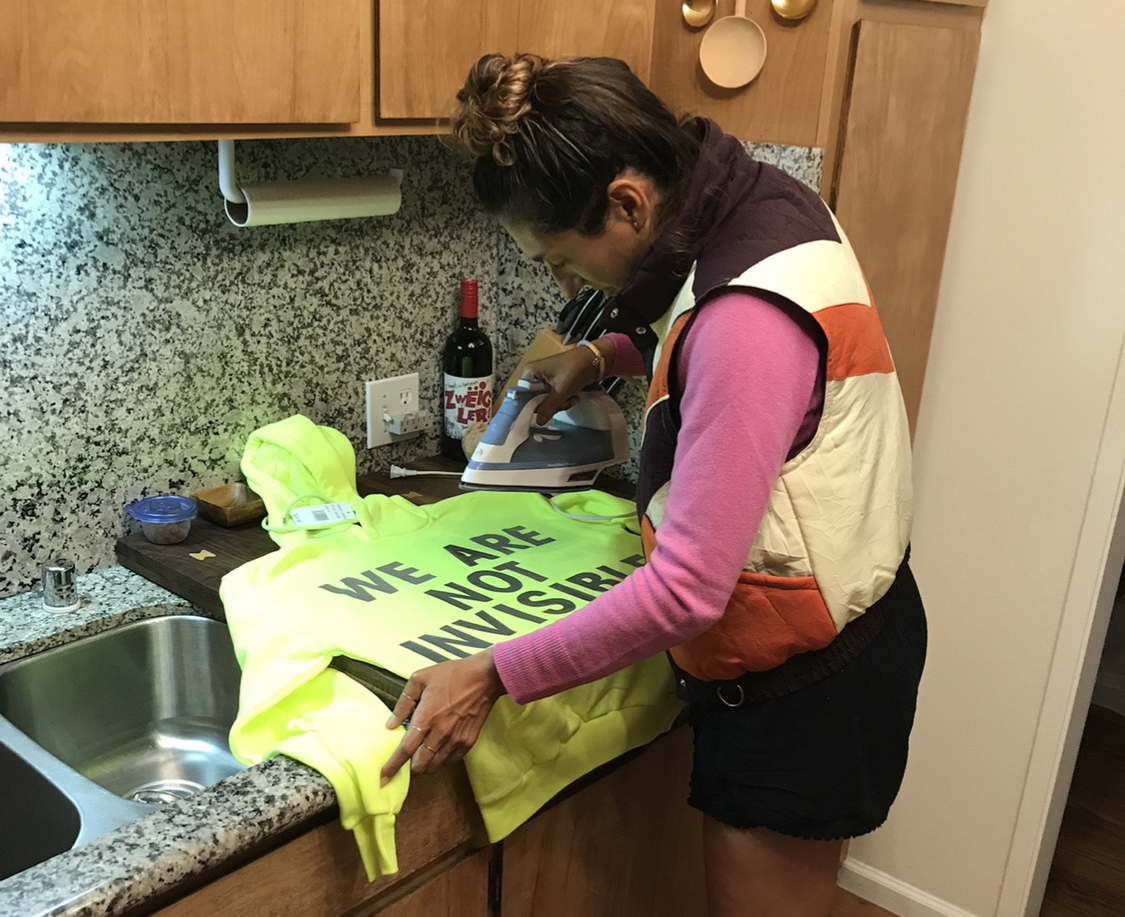

I approached Arleene , “I would love to take what you said and put it into action. So how can we do this? Why don’t you give me a sweatshirt or a sweater that you want to wear and come up what you would say to the public, what you would want to wear as your slogan?” So Arleene shows up a couple weeks later with this bright neon sweatshirt, and she’s like, “Would you mind using bright orange thread to write, “We are not invisible”? I thought “Oh my god, this is amazing. Yes, of course.”

I was expecting just some old hoodie, but the fact that she brought that one, and as I was working on it, threading it together, I just kept going back to her studio in my mind and remembering all the imagery. I thought, “Wait a minute. No. I think we can take it one step further.” That project for me continued where I started asking other women to kind of give me sweaters and sweatshirts and quotes and I titled it WOMXNS WYRDS. And I continued it, working with other women and their words and thoughts. But with Arleene, we kind of stuck with our own project… I ordered a bunch of construction-wear materials and told her we’ve got to take this further. There’s something here.

I had these reflective materials and these strips and asked Arleene if she could get a couple more neon hoodies. She went to the flea market and got some more hoodies from the woman.

ACV: At the Napa-Vallejo Flea Market, there’s different stands for different things. There’s this family of four people, run by the mother and the father, and they’re there every weekend, and they sell these high-vis work materials and work clothing for the men. When you’re working in certain construction areas or in the field or whatever, a lot of the time the companies don’t provide you the proper wear. So the workers have to get it for themselves.

If you go online and look for a high-vis sweatshirt or a high-vis hoodie, it’s $50- 60. They’re super expensive. So these people at the flea market sell them basically to all the Latino workers in Napa. They do it for a really affordable price. So when Ana say, “What’s the sweatshirt that you would wear or that you would use?” I was like, “Oh, well I paint these all the damn time. That’s what I would wear.” I’m constantly painting the vests and the high-vis worker, so that’s what I want.

It was just super incredible and amazing of Ana to get all the different reflective materials so that it wasn’t just thread, and the project became something else. She brought everything over to my studio and we spilled it out. We were like, “Okay, what’s the design? How would we put this tape or the reflective tape here or there?” So we were playing around with different colors and different ideas. Then we nailed our design, and she took it to… What’s that lady’s name that you took it to to sew it?

ATF: Dan. She’s done a lot of my sewing projects in Bernal Heights. So she knows that I’m an artist, and when I asked her to help us it was because I knew we had to use the materials that Arleene uses, but that was so beyond my capacity of sewing something to make it look really nice and professional.

So Dan owns this laundromat cleaner place on Cortland that’s been there forever. I took the project to her because she’s done sarape turned into surfboard covers for me. I’ll bring her sarapes that I’ve cut up for her and ask her to sew it to cover my surfboard. Anyway, so I’m always doing weird artsy projects with her.

So when I brought the project to her she wanted to learn more about it. So I told her, “I’m working with this other woman artist, and she wants to bring in visibility about all the workers. If you notice around in the city, who does the work? Even though they wear these really visible things, do we really see them?” She’s like, “Oh my god.” She had this beautiful a-ha moment where she said, “I love that I get to work on this.” So she was super, super moved by it.

She translated to the other woman that works there all the time, and they were super stoked about it. At first, they were trying to make it work but she realized the material weren’t going to sew well.

So that’s when I did the research for the iron-on vinyl. Then I went back to Joanne’s or Michael’s or one of those, and I was looking at stickers that kind of looked like the Muni prints for the vest. It was super fun to figure out how to design it with Arleene. It was all about creating this really obvious but not obvious illumination.

ACV: I remember even when you brought the final one, I could see it really making an impact and really being beyond us and reaching out to more people. I just was so excited about that, because it was such a beautiful thing to come together and to be able to do something that was so natural. It was a true collaboration.

ATF: When I was brought in by both of the Amys [from Art + Action] for the Census project, over a year ago actually, I brought in this idea of working with this old poster that I had done for this campaign for Marichuy in Mexico. But then I realized there was a better idea, I needed to bring Arleene into the project.

This platform is kind of like what the project needs, this much bigger platform where we can get this idea of visibility out there so it actually connects to a bigger purpose. Then that’s when the Census team met with Arleene.

ACV: Yeah, so I came in, and I was really excited and so grateful for Ana to give me this platform and to bring me into what obviously was her project. So I even went back to my dad, and I was like, “Hey, dad, remember I told you about Ana Teresa Fernández and I worked with her? Well, she did this really amazing thing,” and he was like, “See, Arleene, not everybody is totally…” He was like, “You have to just be nice and remember that we’re all a community.” He was just like an old Mexican wise dad and was just really happy.

So it was really just such a beautiful moment of going back to that Instagram post and thinking, “Oh, somebody actually gave me the platform to raise my voice and amplify it in a way that I couldn’t have done.” I could have maybe done it myself, but it would have taken many, many more years for me to be able to get there.

ATF: I remember back to when I was in Anderson Ranch, and I was like, “Why am I doing this? Why am I here?” I’m so infinitely grateful that I had someone as a student with so much drive and passion in what she wanted to articulate that was so aligned with my principles and what I think is my North Star in life–illuminating truth and community. I was so thankful that Arleene was at Anderson Ranch with me, and I think that she provided me with the motivation to make that week meaningful.

You just never know how interwoven the world can be from those small experiences. That week led to this, because we stayed in touch, because we kept that conversation going, and it was because of nothing else but us. We were into what we were doing, and we just kept that conversation going for three years, because we knew it was a really important conversation to have.

I’ve had people who have pushed to have me kind of rise up. So for me, if given the opportunity, I want to always be able to do that, and especially to people that haven’t had access. If we’re talking about the census and bringing people to have a voice and to count, come on, let’s be real. Who’s not really being counted? In this exhibition, who are we showing that is not being counted that should be counted? Let’s be really reflective of that.

Not only that, I’m looking at Arleene’s piece right now, which is literally made out of reflective material, and there’s no face but just material. So as I’m looking at Arleene’s piece, I’m just like, “Oh my god.” It’s all about reflection. Come on, people. Wake up.