Sat March 7th Open 11 AM–5 PM

June Grant Uses Census Data to Project a Future for Oakland

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

What I love about architecture is that we project a future. For me to start a design today, I have to think about what life could be like 10, 20, or 50 years from now.”

June Grant is the design principal at blink!LAB architecture and a West Oakland resident whose architectural practice combines design, advocacy, and technology. For Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? YBCA commissioned Grant to create We See Ourselves, an artwork examining different neighborhoods of Oakland through publicly available census data.

In light of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? art and civic experience has shifted online. When challenged with converting her architectural artwork, embodying a great amount of physical space, to a digital platform, Grant was quick to offer an innovative solution. “Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve wanted to have a hologram. I’m still waiting!” she joked. “But I’ve always wanted to find a way to communicate a vision, an idea, to the widest audience possible using easy technology.”

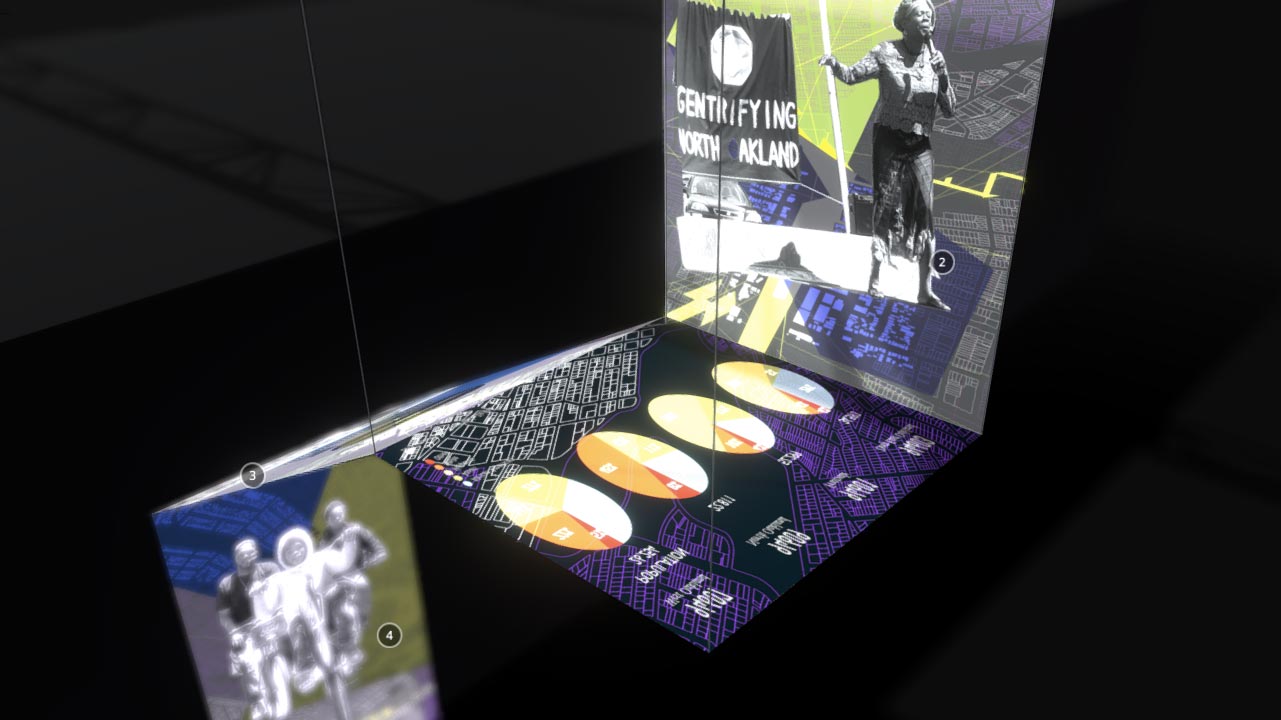

While traditional architectural renderings are flat images, three dimensional modeling in an online platform allows the user to explore the artwork for themselves in their own time. To create a digital version of We See Ourselves, Grant created an interior model of the YBCA space so users could navigate through the gallery and interact with her artwork. Though this digital rendering is a separate initiative from the intended exhibition design, Grant is still excited to have a place to share her work. “Can we now use the technology as a way to engender conversations, until we get into the physical space?”

Growing up in Jamaica, Grant moved to New York and worked in stock market research, later attaining a Masters degree from the Yale School of Architecture. She relocated to San Francisco in 1999, living in the Richmond District by 9th Street. “I thought I was coming to a very diverse city with a large African American population; I thought I was coming to the Fillmore jazz scene. But there was nothing—not as much as I’d seen in [archival] photos. So I felt kind of out of place in San Francisco. And it was always cold.”

Grant first visited Oakland by chance—getting off at the wrong BART stop—before officially moving to the East Bay in 2001. “It felt 10 degrees warmer. And I came across my people!” She chose the Longfellow neighborhood by the MacArthur BART station because of the rich African American political history there, specifically the Black Panthers. “I wanted to be somewhere that had a history of doing things. San Francisco didn’t feel like it had space to try things. Like it was already occupied; things were set. Oakland felt like there was space to try… [pause] something.”

While Grant now lives in the West Oakland waterfront district, the blink!LAB office is still in the Longfellow community by MacArthur BART, where she has connected with numerous organizations in North, East, and West Oakland. “When I opened my office—we’re in a small retail space—it was for a specific purpose. I believe architects must be visible in communities to be of social value. It’s essential that the community knows that I’m a resource they can call and ask a question. Communities must see us at work, and we must see the community at work.” Grant is one of only 478 African American female architects licensed to practice in the United States.

Grant works extensively with communities in a variety of ways, from designing in-law units to promote accessible, affordable housing, to creating and fabricating custom sound absorption panels for the Oakland Public Conservatory of Music. But what she values most is building a long-term vision for communities. She describes it as similar to how a real estate developer might hire an architect to create an illustration of what a building could look like, before finding a bank to finance a deal. “I provide solutions through an architectural approach to how these communities can bring pride back in the physical environment, so that the physical environment matches the pride and the spirit of the people who are there. I create a vision for the piece of land or commercial corridor, and then we provide [a model of it] for that community.”

In her work both in commercial architecture and community work, Grant researches census data and public government data to better understand the local neighborhood, from population demographics to tree and lamp post locations. “[Looking at the data] allows me to understand who’s there. You don’t sense that kind of detail when you walk the ground, but you can see it through the census.”

“I’ve learned that when I compare census data from the four distinct regions, the information is often contradictory to folklore”

Every ten years, data collected in the census count determines government funding allocations for education, housing, transportation, and more. Grant hopes that communities will use this year’s 2020 Census as an accountability tool. “So far it’s been a one-way relationship, right—we give [the government] our information, and then the federal agencies decide, ‘We’ll give you some funds,’” she said. “But nowhere in that relationship does it say that the city of Oakland or the state of California is held accountable for how those funds are dispersed. Like, does it match the census?”

Grant also considers the census data as an incredibly important advocacy tool. “The community might say, ‘We need more parks!’ Or they might believe that they have enough parks. And when I compare the census data, I can show the discrepancy between what they believe they have, and what others have,” she said. “So I use the metrics to argue my point, and to arm the communities to argue their point.”

When she was asked to contribute to Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?, Grant was excited about the opportunity to explore architecture as an art form, but also challenge the scope of the exhibition. “Most exhibitions [at YBCA] do not take advantage of the volume of the building, so [the artworks] tend to be more eye level.”

Grant described her artwork We See Ourselves as an unfurled box kite, anchored to the gallery wall and extending all the way up to the ceiling. Each of the “grand opening” banners that make up the kite are strung together with metal cables, and bend in different directions to create a hanging sculpture.

If We See Ourselves was spread out on the ground, it would map almost the entirety of Oakland, from West Oakland by Highway 980 to MacArthur BART and Rockridge to Fruitvale and East Oakland. Featured atop the maps are images of community members, each representing social issues that are directly relevant to the corresponding geographic location.

In the West Oakland section, the panel closest to the ceiling, Grant included an image of a protest by Moms 4 Housing, a collective of formerly unhoused women who reclaimed vacant homes in a fight against speculative housing and ignited a national movement for housing rights.

The North Oakland panel features Frances Moore, a famous North Oakland housing activist known as Aunti Frances. As the city has pushed out its longtime population and increased housing and rent prices, Aunti Frances has been a symbol for North Oakland and the protests against gentrification.

The central section of the work offers colorful pie charts of census statistics, from population to demographics. “I’ve learned that when I compare census data from the four distinct regions, the information is often contradictory to folklore,” Grant said. “People will say, ‘Oh, [East Oakland] is a majority tenant population, they’re mainly renters out there.’ That’s not true! Out of the four communities, East Oakland has the least [percent] of renters, and they’re predominantly homeowners.”

The Fruitvale panel examines the large homeless camp on 37th Avenue near the Home Depot, with a photo featuring an older man and his dog. “I wanted to show the humanity of the people who are there,” said Grant. “They are capable of love just like anybody else. They care about their pets just like anybody else.”

The East Oakland section of the work, the final piece of the installation anchored to the wall, features the Scraper Bike Team riding down International Boulevard. “These kids make their own bicycles from scratch,” Grant noted. “They came together around bicycles, and independence in transportation. They’re very focused on sustainability. If I mentioned deep East Oakland to the average individual, the first thought that comes to mind is not sustainability.” Grant chose this piece to be closest to the ground so that the audience would be physically eye to eye with the kids on the wall, staring back at you as you’re staring at them. “The piece is kind of an homage to the people of Oakland, but using the census data and mapping as a way to remind us that the census is really about humanity.”

What does Grant hope that viewers will experience from We See Ourselves? “I’m hoping that if you’re a San Franciscan, you’re far more curious about Oakland, and if you’re from Oakland, you see yourself represented with pride. Someone in Oakland decided to plant a foot—a big foot!—in the exhibition by paying attention and really spotlighting the communities there.”