Sat April 27th Open 11 AM–5 PM

Finding Ways to Better Understand Your Neighbor

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

Leah Nichols is an award-winning filmmaker and designer based in San Francisco. She is best known for the animated short film, 73 Questions (2018 San Francisco International Film Festival selection, 2018 Social Impact Media Awards winner). Her work seeks to celebrate connections across differences, expand media representations of family structures, and eliminate stigmas related to mental health.

Come to Your Census co-curator and YBCA Associate Director of Public Life Martin Strickland sat down with Leah Nichols, on April 20, 2020 to discuss the intentions behind the film, how we stay connected to our neighbors during shelter in place, and how we can break common misconceptions of people we pass everyday.

Martin Strickland: Hi Leah, thank you so much for doing this. Can you describe your video, 73 Questions?

Leah Nichols: The film follows Steve Jones, a resident of San Francisco who has lived here longer than I’ve been alive. So, for 40 years. The film is a 73 question interview as I perform his daily walk with him from Sixth Street, where he lives in the Tenderloin, to Capp Street in the Mission, where he regularly hangs out.

LN: The structure is based on a rapid-fire, interview-style questionnaire, exemplified by late night talk shows and specifically a YouTube series by Vogue called 73 Questions. That style mostly focuses on celebrities and the whole point is to show someone that feels foreign and out of touch as known and familiar. So, I thought that structure was really helpful in making someone familiar who you might otherwise not know or might otherwise feel very different from you–someone sitting on the street.

MS: Can you talk a little about the style of the video, and what you had in mind when you thought of following Steve around?

LN: The film is stop motion with colorful animation that expresses Steve’s poetic spirit. Actually the initial footage was so bad that Steve and I agreed together to switch to animation. We wanted the mood to be whimsical, that was one of his words and I really took it to heart.

MS: So, the animation portion was a happy accident, then?

LN: Yes. I wanted to avoid using the conventional style of representing people on the street. You know the kind– this national geographic, hyper-realist, zoomed-in, dirty, wrinkly face. That’s kind of disgusting to me, it’s objectification. I wanted to do something different and more creative in representing Steve.. That included getting his input. He wanted color, he wanted whimsy, and he wanted it to be fun. Animation works well in this case because it allows viewers to suspend their assumptions and judgments about who he is based on age, race, his clothing, etc. Animation makes it easier to simply get to know him as a person.

MS: How did you first meet Steve? When did you broach this idea with him and what was the creative process between the two of you?

LN: For better or for worse, there was no plan. I had just quit a career in architecture and was feeling pretty lost, but I knew I wanted to do a project in the neighborhood. A lot of my work is hyperlocal in the Mission. The people I see regularly are the most important to me.

There’s a Ted Talk by Taiye Selasi, called “Don’t ask me where I’m from, ask where I’m a local.” Taiye talks about situating yourself in the world, not where you’re from, not where your passport says, not where you’re born necessarily, but where you know people. Where do you know people’s names, what businesses do you frequent, etc. And that really resonates with my work style and where I give my attention and care. I think it’s best to meet people when you’re laughing or crying. I met Steve when I was crying at a mutual friend’s memorial service. A homeless man that lived on my block of Capp Street for years had passed away. He was the most consistent presence in my life. I saw him when I went to work at 9:00 am and when I came back at 5:00 pm.. I was crying at his memorial service, which was a beautiful gathering of people. The dudes from the Mission who had been hanging out there for decades came, newcomer people in tech who had only lived on our block for a year also came, my roommates and I were there, and his family was there.

It was this great gathering of all different kinds of people to celebrate one man who connected us all. And that’s where I met Steve. I was trying to read something and I couldn’t get out the words and Steve just yelled, “Buck up.” I think there’s something beautiful about meeting someone when you’re crying because you’re already at your most vulnerable.

I had just as many assumptions about him as anyone else might have about a guy hanging out on the street. I always want to acknowledge that power dynamic between the two of us. I am the filmmaker and I made editorial decisions. I’m a person with stable housing. But I really wanted to explore what this could look like as a collaborative piece between people with different levels of privilege, access, and knowledge.

Steve definitely has more access to knowledge than I have in certain parts, especially within San Francisco and in the neighborhood. When we walked from the Tenderloin to the Mission–normally only a 30 minutes walk––it took us three hours because he stopped and talked to everyone. We had to stop and talk and meet people’s pets. It was a beautiful glimpse into this community.

The goal of the film is to evoke curiosity and share the excitement of getting to know someone. Steve chose all the music, we agreed on colors together, and to me it’s a success because he’s represented the way he wants to be represented.

MS: A lot of people who come from a place of privilege, and that privilege base can just be having stable housing, are introduced to a community that is, either temporarily or not, experiencing houselessness through various forms of media that you’re never really sure what agency the the person being interviewed had in their representation, which removes the personality from the actual piece.

That’s what I think is so obvious whenever you watch this piece, that Steve has a say in how he is represented. Was there a conversation with Steve about that before you all started? That he was like, “Look, I will do this if I can be represented in X, Y, or Z way, that it feels honest to me.”

LN: No, we never had that conversation. He had so much trust in me and I think it honestly helped because when we met, the power dynamic was flipped. I was distraught. I was the vulnerable one. And that power dynamic has shifted throughout the process. So when we actually recorded this, I was walking with him with a camera and he decided the route.

We went through the Tenderloin, down Sixth street, and then he wanted to turn onto Valencia Street and the Mission. We could hear people’s reactions, a couple of people yelled at me to leave him alone, assuming I was exploiting him. They thought I was just some hipster working for Vice filming without his permission.

In different circumstances and context, Steve is the vulnerable one. People unaware of our relationship saw me as a danger to him. That really surprised me and I think speaks to people’s fear of difference and how rare it is that you see friendships that are between people that look different from each other. That obvious fear of difference is unfortunate and has dangerous effects at both a policy level and a personal level, but also just results in missed opportunities of unexpected creativity and connection.

MS: I think that that’s an interesting lead into this other question that we’ve been asking a number of people. For you as a filmmaker, what are some strategies that you find have been useful for breaking through political disengagement or distrust to be able to hone in on the subject at hand?

LN: Laughter, I think. Like I said before, I’m totally connected to people when laughing or crying. I feel most connected with someone when I’m laughing with them. One of Steve’s friends described the film as a laugh-a-minute, better than SNL, which is just the best review ever. I think joy is something that is perhaps overlooked, especially when we’re dealing with underrepresented populations or marginalized populations. The tendency is to want to do an investigative piece that’s super serious and fact-driven and that’s necessary, but also I think it’s necessary to represent people’s personality, their humanity.

The human condition means you have bad days and good days, and even people living on the street have good days too. And people living in homes have bad days. I’m not romanticizing any situation specifically. Some of the feedback I got from 73 Questions were people criticizing it for romanticizing Steve as a whimsical poet philosopher, which I totally rejected.

That feedback speaks to the lack of representation of people in unstable housing–this idea that you must have a sad story and have experienced tragedy if you have unstable housing. While those stories are important, I think the stories that have joy are also important. That’s what I feel like all movements fighting for justice are essentially fighting for, this access to joy.

One other thing I want to say is I think imagination and the ability to dream is really important. I think given my relationship to the creative field and film, the best thing I can do is create and imagine worlds that are better, different, and more equal and joyful than yesterday.

MS: 73 Questions was not commissioned for Come to Your Census. The film is now three years old, correct?

LN: Yes, and then it was at the 2018 San Francisco Film Festival, which was really special.

MS: I know that you already had a relationship with Amy Kish [Founder + Artistic Director of Social Impact, Art+Action and co-curator of Come to Your Census] and whenever I came in and partnered with her to develop the curatorial framework, I was really interested in showing this film. How do you see the film 73 Questions relating to the 2020 Census? And then what do you think is at stake for the communities that you’re representing in that film by taking the Census or not?

LN: From both my and Steve’s point of view, I think hopefully the theme of the film is also how it relates to the Census, and that is personal agency. We’re all people. Sometimes I get the question, “How do we change public opinion?” Which in another way is, “How do we get people to do stuff? How do we get people engaged? How do we get people to take the Census?”

And I think it’s important to ask yourself how you place perception in relation to the world. Where you choose to spend your time and your money in your care and attention. Spending time filling out the Census has an incredible impact. I just wish people knew their power, essentially.

MS: So in this time, in this moment of social distancing, how do you see forms of visibility changing and how do you think that folks can remain visible who might not have been honestly hypervisible to begin with?

LN: If you take a walk down Market Street right now, you’ll see who’s left outside. I think ironically they’re the least visible people–the people out on the streets right now. I haven’t processed that yet but it is a very distinct result of this crisis around who has the privilege of having shelter that they can retreat to and be safe within.

MS: I look at this question too and I don’t have an answer for it yet either. But these are questions that I like to pose to people as we think through them together.

LN: You’re giving me more time to think with these questions, which is good. There’s a lot of visibility of people waiting in line for food in places, that’s another snapshot that I’ve seen recently. It’s harder to ignore the inequities right now because they’re just more concentrated. Privilege and the lack of privilege is so visible right now in our public spaces. I think that’s having an impact and I’m not sure what yet.

MS: On a personal note, during this strange weird in between time,how are you taking care of yourself?

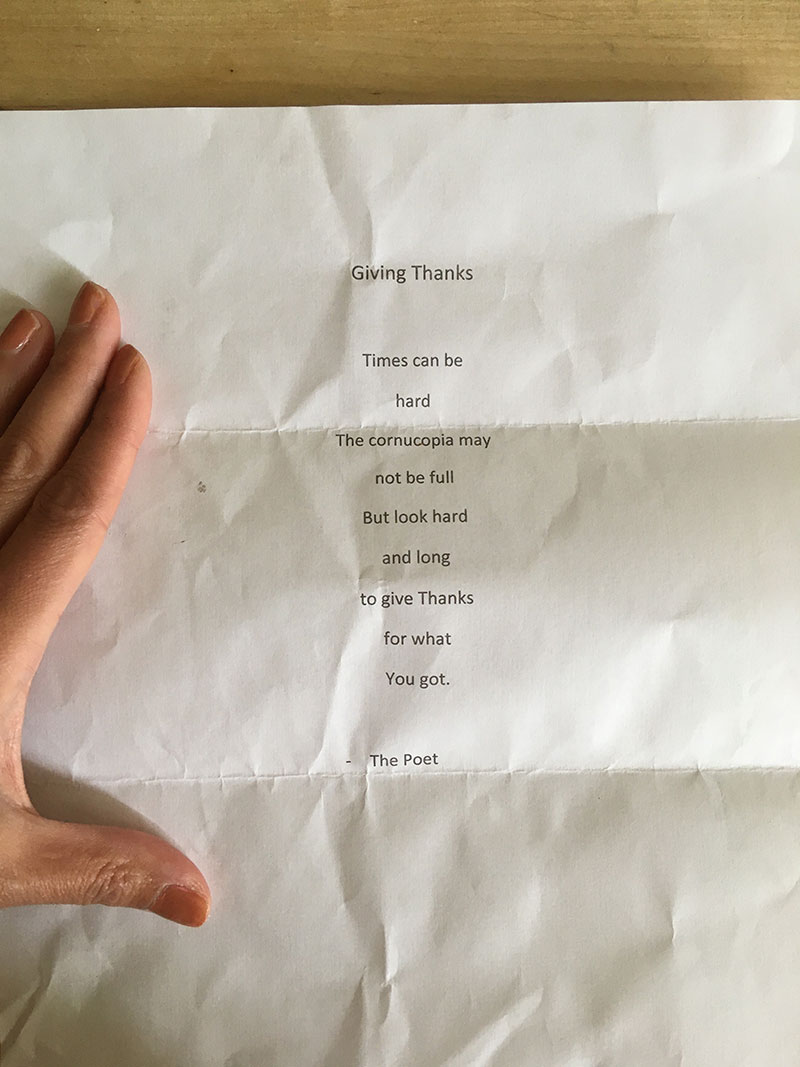

LN: I’m writing Steve letters. That’s something that he’s wanted me to do for a long time and I never did. He would actually give me self-addressed envelopes with stamps but I wouldn’t write because I would just see him in person. He writes me poetry. The last one he wrote was about being thankful. So, that’s a different way of connecting with Steve specifically. My roommates and I did an art installation on the fence outside of our home in the Mission. It felt like a way to be expressive in times of survival and panic. It feels like there’s less room for expression but it’s still so, so important that we try. Whether that’s through the census, through art, writing, whatever.

MS: And how do you feel like you are, if you are able to, stay politically engaged at the moment?

LN: Honestly Martin, I’m not doing many things differently. The values in my work are still present and the type of work I’m doing is still something that I’m proud of. I still have the same projects and I think the problems in society have always been there. This is just illuminating them.

MS: I feel like so many of us are asking both in our personal lives and in our artistic practices, however we can express ourselves and what feelings are real. But there is a really calm force in remaining steady, a steady course throughout these times.

LN: There’s such a spectrum, right? A lot of my family members are healthcare workers and they’re treating COVID patients and dealing with ventilator shortages. That’s definitely a different type of way to work. But I think both things are needed right now.

The Guardian had something about an experiment that was done where someone cut up a newspaper every day for a year. It was basically to make the point that you don’t need to read the news every day. The things that are important will be consistent themes in the news, like climate change for example, and actually sometimes being distracted by the everyday newscycle isn’t helpful.

MS: Leah, thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me and for allowing us to embed 73 Questions on our website for people to watch until we’re able to get back into the physical gallery space. Take care and talk to you soon.

LN: Thanks, Martin. Looking forward to seeing you in person sometime soon, hopefully.