Sun January 18th Open 11 AM–5 PM

Experience the impact of art on healing with The Nocturnists

“How can we use storytelling and the arts to heal ourselves, and heal each other?” This is the central question driving The Nocturnists, a live medical storytelling event and podcast created by Dr. Emily Silverman, an internal medicine physician at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

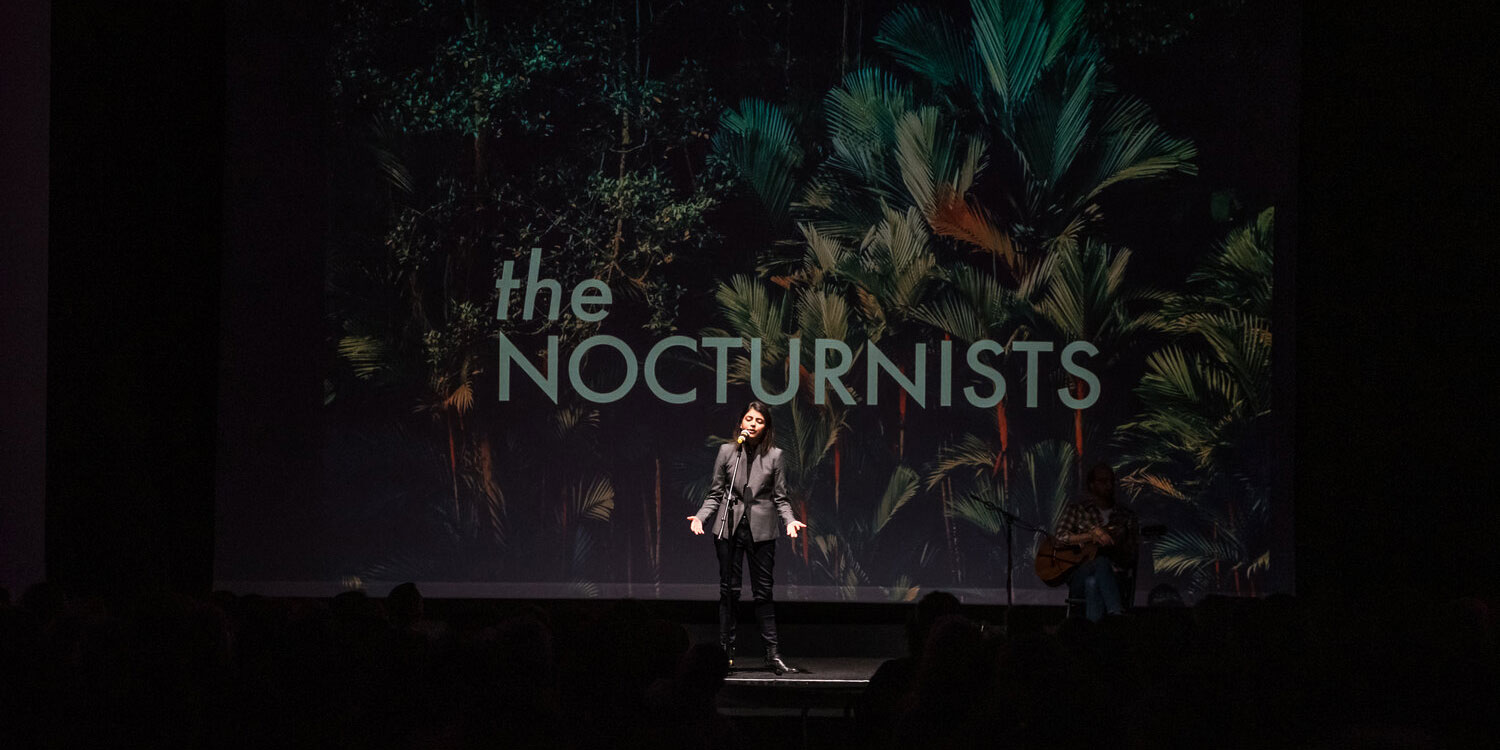

Named after health care professionals working the night shift, The Nocturnists curates personal stories from local doctors and health care professionals for each show, exploring themes from love and death to mistakes and learning. Each physician shares their story live onstage, offering the audience a glimpse of the practitioners’ insight into human experiences.

“We witness some of the most pivotal moments in people’s lives,” said Dr. Alison Block, a family doctor specializing in women’s reproductive health and executive producer for The Nocturnists. “And then we, as humans, also have reactions to those moments. I think that interplay—between taking care of ourselves and taking care of others—has a lot to teach those of us in health care, and also those in caregiving roles in other parts of life.”

“It’s really important that we remember that doctors are also people,” said Silverman. “I’m really curious about exploring who are doctors today, what are the challenges they face, and how do we amplify that? I hope, in doing so, we’re able to humanize the physician and humanize health care.”

Silverman initially began looking for an artistic outlet during her residency at UCSF, before forming The Nocturnists. “At the time, it felt like my creative side had been stripped away by the medical education industrial complex. I felt disconnected from my friends and family and my own sense of wellness and humanity.” For Silverman, it was critical to her personal wellness to begin a creative project. “The art was the oxygen. This was kind of what I needed, to stay alive as a human being.”

What began in 2015 as a stream of consciousness blog about Silverman’s personal experience as a doctor rapidly gained popularity among her friends online, both in the medical community and outside. Looking to expand the project, Silverman considered incorporating guest writers, starting a literary magazine, or even creating a documentary film, before landing on a live storytelling show, inspired by The Moth at Public Works in San Francisco. “There’s just something about that electricity of a show unfolding right in front of your eyes,” Silverman said. “You’re sitting in a crowd, and you can feel the warmth of the body next to you. It’s not like on your couch, watching Netflix; it’s a live experience which brings a community building feel to it.”

“The art was the oxygen. This was kind of what I needed, to stay alive as a human being.”

Adelaide Papazoglou, a medical anthropologist, filmmaker, and head of story development for The Nocturnists, agreed. “The live shows provide an experience of a community coming together, not just to listen to stories, but also to open themselves up to the experience of another, whose fears, vulnerabilities, and demons are laid bare. There can be something quite mystical and almost religious about that kind of experience, and, to me, that’s what storytelling throughout human history has always been about.”

The Nocturnists is careful to balance patient confidentiality with the integrity of the storytellers’ narratives. “There are some doctors out there who believe that no doctor should ever write anything about a patient, ever,” Silverman said. “In my mind, it puts the doctor in a creative prison, not to be able to express themselves. I think there is a way to do that responsibly and ethically.” The Nocturnists’ creative team ensures the storytellers take steps to ask patients for permission and scramble personal details.

Launched in 2016 as a house gathering for 40 people, The Nocturnists’ live show has sold out theater after theater in San Francisco before landing at YBCA for its January 2020 performance. “Health care workers and the broader public are hungry for these authentic stories and moments of connection,” said Block. “We hear again and again from our storytellers that the experience of sharing their stories on stage is pivotal and life-changing. Offering that outlet for creative expression and catharsis to others has been an enormous gift.”

Silverman noted that Daniel Lowenstein, the executive vice chancellor at UCSF, once shared onstage at a Nocturnists show how the death of his mother shaped him as a doctor. Recalling her conversation with him afterwards, she summarized his comments: “The experience of stepping onstage without a Powerpoint, and it’s just you, and the mic, and the audience… It was terrifying, and so gratifying.” For Silverman, to know that his storytelling experience “really had a special flavor to it, and that the stakes felt higher… that’s exactly what we’re going for.”

“You make a decision to share a little piece of your soul with the audience that night.”

In 2018, The Nocturnists took its stories online, with Silverman hosting a podcast that incorporated narratives from health care professionals across the United States. Silverman remembered receiving an email from a hospital chaplain who discovered the Nocturnists podcast: “It said, ‘As a chaplain whose hope it is to see a gentler and kinder medicine emerge from our broken system, these stories are like little cups of cold water in the desert.’” The Nocturnists encourages storytellers to lean in to the element of vulnerability that resonates most strongly with the audience. “You make a decision to share a little piece of your soul with the audience that night,” Silverman said. “You really bring yourself into the story, and show us how this transformed you.”

Outside of the theater and the recording studio, Silverman strives to bring her storytelling knowledge from The Nocturnists into her health care practice. “So much of our psychology is about the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, and about other people,” she said. “I think bringing some of that narrative framework into the space of healing can be really important for people.” Papazoglou noted, “Diseases don’t exist apart from the discourse about them. Cancer has the meaning it does for people because of the narratives it is couched in.” Silverman commented that this storytelling perspective tool can be useful for doctors as well. “How do I help my patient incorporate the existence of this illness into their life narrative? How do I help them view themselves as the hero of their own story?”

Storytelling and the arts are valuable tools in the healing process, and often underrepresented and underappreciated in medical environments like hospitals and clinics. “When institutions take the time to bring art in and soften the bright lights, loud noises, and blank white walls,” Block said, “we can create an environment that is not just recuperative from a medical perspective, but can also offer healing on a psychological and spiritual level.”

Though many studies have demonstrated the positive impact of art therapy on mental health, Silverman suspects the arts may yet have a stronger impact on overall health than is currently recognized. “Which is not to say that you can heal your pancreatic cancer with dance,” she pointed out, “but I don’t know—maybe you could reach a place of peace about your prognosis more easily if you engage with your disease through an artistic lens.”

Silverman believes there is great potential in using art as medicine, and hopes to see institutions dedicate funding toward studying how the arts can promote healing both in individuals and in communities. “San Francisco is such a cultural and artistic capital, and a health care capital. Why are these industries not interfacing more? Just get them talking and see what kind of ideas come up. I bet that there would be a lot of sparks.”

“Making our arts institutions accessible to a broad public,” Block said, “is one of the most important things we can do to promote the health of our communities.” Papazoglou added, “Where would any of us be without the arts? Didn’t Nietzsche say, ‘Without music, life would be a mistake’? Without art, I think the world would be a much less happy, less healthy place.”