Tue October 28th Closed

Ashara Ekundayo in Conversation with Lava Thomas, Part 2

Family, Artifacts, and the Census

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

Ashara Ekundayo is an independent curator and cultural organizer in Oakland, California. She is a member of the Art+Action Curatorial Committee focused on developing the YBCA art & civic experience Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America?—comprised of Martin Strickland, YBCA’s Associate Director of Public Life; Sarah Cathers, YBCA’s Director of Public Life; Amy Kisch, Art+Action Founder + Artistic Director of Social Impact; Brittany Ficken, Art+Action Executive Producer + Project Director; and Candace Huey of re.riddle—to initiate conversations about the Census and visibility. Specifically, Ekundayo’s work and social practice centers the lives, creative labor, and archives of Black Womxn and Femmes through exhibition and public cathartic ceremony.

This is the second in a three part series of conversations with Lava Thomas —whose artwork is also featured in Art+Action’s city-wide outdoor campaign, as well as in the coalition’s free open-sourced digital toolkit—and serves as a precursor to a two-part panel discussion called See Black Women, moderated by Ashara and in conversation with eight Bay Area Black Womxn artists and curators to talk about visibility, grief, pleasure, and our present paradigm shift in culture and practice. Join us for a two-part conversation that will take place on Tuesday, May 19 and Tuesday, May 26 from 4-5:15pm PST. Participants include Asya Abdrahman, Sydney Cain, Erica Deeman, Angela Hennessy, Tahirah Rashed, Lava Thomas, Sam Vernon, and Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo. Please enjoy Part 1.

Ashara Ekundayo: We’ve been talking about being counted because our global awareness of death has come at an even more rapid pace because of the COVID19 pandemic. It seems to be across the board in terms of age and class. Yes, there is a disproportionate amount of people of color, non-white folks, who have underlying social issues and health issues that make us more vulnerable, particularly to something attacking our lungs and our being able to take a breath. This pandemic is about the breath and it is about disparities.

I want to talk a bit more with you about being counted as this is a Census year. This idea of naming ourselves, claiming ourselves, and honoring the moments we have with each other. I want to also start by asking about your name, Lava. Is it short for something else? Is it a name your family made up? Talk with me about naming ourselves and being counted as Black folks.

Lava Thomas: It’s really funny.

AE: Black folks…

LT: We name ourselves.

AE: We do.

LT: We name ourselves and so many people think that Lava is a name I have given myself as an artist.

AE: Your artist name?

LT: It is my artist name, but also Lava is my family nickname. My full name is LaVynell and my mother combined two names, her middle name which is Wynelle and a good friend’s name Lavella. We’re creative. She came up with LaVynell. My family is notorious for nicknames and I have a kind one, it’s not based on anything out of my personality which is usually how nicknames go, like how you look when you’re a baby or whatever.

AE: And you’re first born?

LT: Yes.

AE: Yeah, it could have been bad.

LT: It could have been bad but instead they just shortened LaVynell to Lava and that’s who I’ve been since I was a child. As Black folks we practice whatever control we have and naming ourselves is one way to tell the world who we are on our own terms.

AE: That’s right.

LT: In terms of being counted, we are in a Census year and I think about the Census being so important especially during this pandemic, because the data is used as a baseline to determine the racial disparities among communities of color. Being counted is extremely important.

AE: Have you done the Census with your family?

LT: Yes.

AE: I know you have many stories about the importance of the Census, the importance of counting for your family and also for your art practice.

LT: The Census was extremely important in my discovery of my ancestors in Decatur, Texas. As I said, I grew up with my grandmother and my great grandmother and I’ve listened to their stories my whole life. My grandmother would visit Decatur, Texas every year because she was involved in a restoration project for the one-room segregated schoolhouse that she and other members of my family attended when she lived there, but I had never visited until last year.

“It’s been really important for me to create a visual archive of my ancestors that I can pass on to my own progeny so that they know the story of our family, which is a remarkable story of resilience and ambition.”

AE: So you didn’t go “Down South” as a child as many of us who grew up in the “North” did?

LT: No, I didn’t. My family, for some reason, did not. I had friends who were sent down South during the summer but we weren’t and I don’t particularly know why. When my grandmother would go she would always go alone. I grew up listening to these stories that really captured my imagination. When I was invited to give a lecture in Texas I decided to visit Decatur for the first time and I found a lot of the landmarks that my grandmother talked about, but I hadn’t yet done any real investigative work. I went to Ancestry.com and I was able to find my great-great-great-great grandparents in the 1900, the 1910, and the 1930 Census.

And because my great-great-great grandparents were one of the first pioneer families in that county and the first Black couple to get married legally in that county, there are a lot of documents in relation to my ancestors and my family in Decatur, Texas, but the Census was really the cornerstone of the information. The Census data has everyone listed in the household, where their parents were from, where their parents were born. I learned my great-great-great-great grandmother had been enslaved, my great-great-great-great grandfather was a free man from Ohio. I even found out information about the family who owned my great-great-great-great grandmother through the Census.

AE: You had the family stories that you listened to and then you were able to find the paperwork. Then you visited these places?

LT: So last year actually, the Wise County Genealogical Society organized a posthumous memorial service for my great-great-great-great grandfather, who had fought in the Civil War and didn’t have a tombstone. He didn’t have a military funeral so they organized all of this for him and a lot of the members of the family from all over descended on Decatur. It was really great.

I met relatives in Decatur and Fort Worth, Texas for the first time, and sat down with an aunt who looked at a lot of old photos. This aunt shared with me all of the stories that my grandmother didn’t have. She took me to the baptist college where my great grandfather had worked as a janitor and wanted to take classes. Because of segregation they had him sit in the janitor’s closet and listen. They wouldn’t let him sit in the classroom.

AE: Have you created portraits of your Ancestors?

LT: I have. I discovered my grandmother’s photo album a decade after she died. As a child she never showed it to me. I don’t remember her even looking at it, but her home in Los Angeles is still in our family and I was there trying to find some sheet music because my grandmother played the piano. I was looking around and came across this album. Since then I’ve been drawing portraits of my family from her album. For many of the portraits, the people who would have information about them are already dead, but I know that they are ancestors of mine because of their prominence in that album.

I think a lot about how, as Black folks, we often don’t even have these kinds of family artifacts. We may have an oral history, but we may not have the images to go along with it. So it’s been really important for me to create a visual archive of my ancestors that I can pass on to my own progeny so that they know the story of our family, which is a remarkable story of resilience and ambition. Think about it, a bunch of women left Decatur, Texas to come to Los Angeles because they did not want to deal with Jim Crow segregation, because they wanted freedom in terms of education, because they wanted equal access and equal opportunities.

AE: What you’re speaking to is the creation of our own artifacts.

LT: Exactly.

Part 3 will be released on Monday May 18th, 2020 on YBCA’s Zine.

Ashara Ekundayo is an Independent Curator and Cultural Strategist. Her current multi-media platform #ArtistAsFirstResponder excavates, documents and archives the stories of artists whose creative practices save lives and heal communities. Learn more at www.Ashara.io or follow them on IG @blublakwomyn

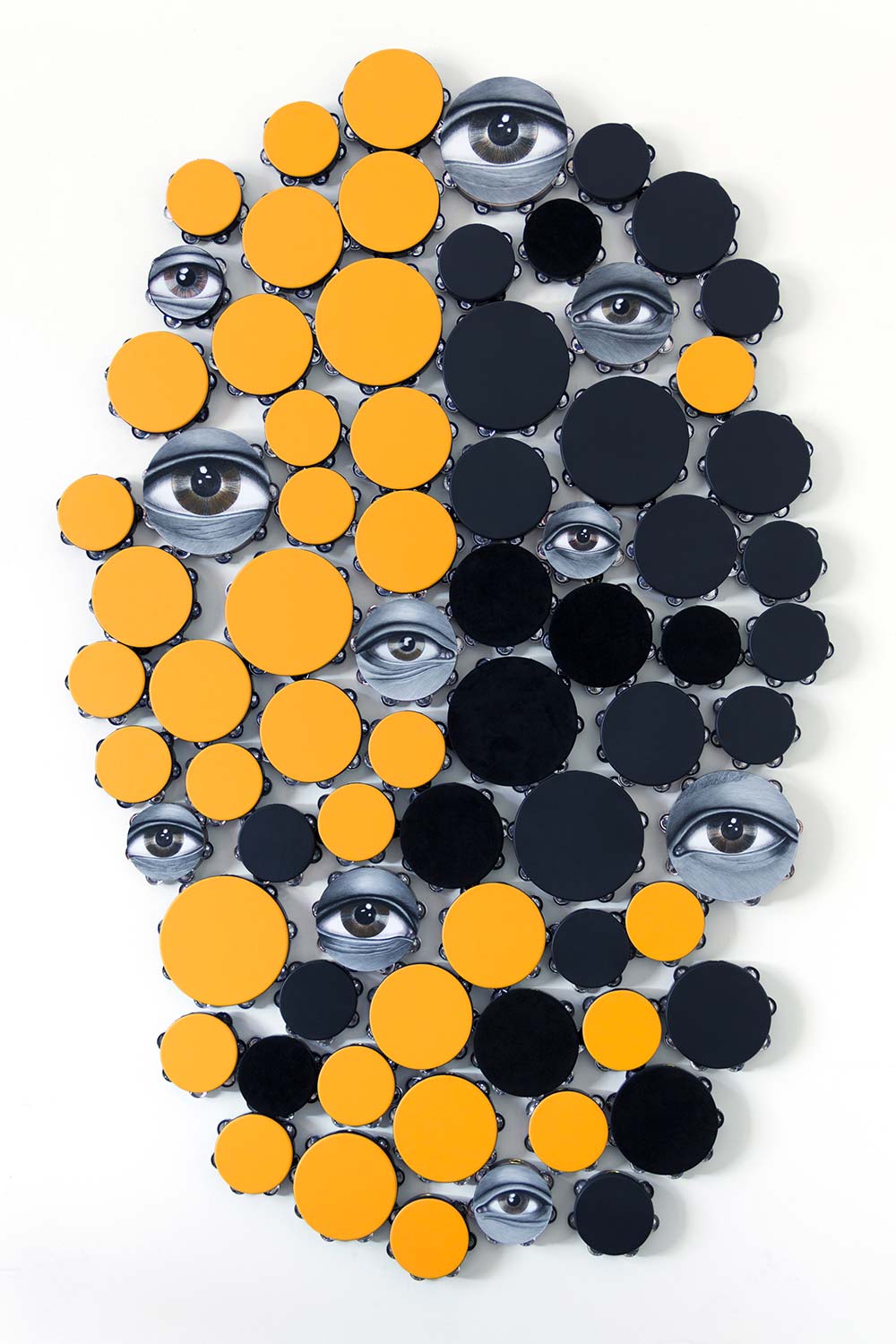

Lead image: Lava Thomas, Self Portrait II, 2016, from the Childhood series, water-based oil on canvas, Courtesy the Artist.