Fri January 30th Open 10 AM–5 PM

To Find Spirit, To Survive: Reflecting on Artistic Process During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The 2019-2020 YBCA Public Participation Fellow cohort was originally gathered to collaborate and build on communities-based projects that demonstrated the mobilizing of public participation. However, as the Fellows worked on bringing their work to fruition, the world was hit with COVID-19. The cohort were then challenged to grapple with the question: what is public participation now?

My artistic practice is all about other people: facilitating them, holding space with them, co-creating, directing, feeling into the group mind of an ensemble. Bodies, together, moving as one. Bearing each others’ weight, sculpting our stories through shape and movement— holding sacred the live act of performance. Gorgeous, fleeting moments of expression, the intimacy of being witnessed in ritual, of losing yourself in trance.

With the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, I felt anger at having to abandon these modes of being with others. I resisted transitioning to the digital space, dreaming of papier-mâché caught in my fingers, clothes sticky with paint—my plan had been to build giant puppets to amplify street actions, and I was utterly deflated at the brutal and sudden silencing of social protest. I was not ready to let go of my idea to host workshops and art-builds to generate participatory performance/street theater with organizers in a number of movements where I’m embedded: youth-led campaigns for environmental justice, transnational solidarity with Indian struggle against Hindu fascism, and community solutions to safety that don’t involve police or prisons. The YBCA fellowship enabled me to incorporate giant puppetry and mask-work into my practice, learning alongside my friend and master artist Levana Saxon. Seeing this opportunity disappear was too much, as if my voice was closing in on itself. I nearly shut down my art altogether, only to be lifted up and held by community members who showed me what was possible.

All of us in the fellowship cohort were reeling with the prospect of having to surrender our original projects to this monstrous unknown. The team at YBCA advocated for the spaciousness that we needed to thoughtfully re-enter “public participation” as artists. While shaken by the economic devastation to arts institutions, they nevertheless prioritized our independence in continuing to make public art interventions. Particularly helpful were the peer laboratories where I could consult with other socially-engaged artists on how they were adapting, thus reminding me of my own brilliance and imagination. From falling to pieces, I was held by their belief represented in this letter to artists: “This is what we train for / Your skills are sorely needed / Make the art this moment needs.”

I was able to pivot to a modality that could accommodate the drastic changes we were undergoing, ultimately offering virtual experimental embodied arts sessions. With Saxon, my co-conspirator, we called them Social Closening workshops. Many people responded with gratitude at the terminology we were claiming. Drama therapist, actor, and vocalist Tia Phillips says, “I shiver at the term social distancing. In these times we live in, it seems very much contrived to keep us assuming and looking at each other as enemies and as dangerous.” She has pushed back against these negative currents by performing in neighborhood concerts, allowing people to be in each other’s company “within the brightness of music that has the ability to connect us from all walks of life. Bringing folks together, being part of that ‘closening’—that’s self-care, too. I need to care for my heart because it expands during challenging times.”

There was heart-medicine in our virtual embodied workshops. I had been skeptical that it would work at all, still in denial about the new reality of physical dislocation and stuckness. I was committed to simulating the experience of being physically together as best as we could. While we couldn’t literally follow the customary group agreement of “unplug and be present,” we maintained its essence. We introduced ourselves by drawing a picture of our home/family/extended microbiome—all the beings whose immune systems we are trying to protect. We held up our papers to the camera and took a breath, noticing what it looks and feels like to inhabit separate bubbles. I was shocked and heartened by the connection I felt among all of us, through our computers, naming and validating shared experiences of frustration, loneliness, confusion, stress, and anxiety.

We played with simultaneous sound and movement: what is it like to be in the world right now? Do a repetitive gesture representing this. What strength or inner resource are you calling on to get through these days? Embody that, then try on someone else’s. We clearly instructed whether mics should be on or off, at times relishing in the messy asynchronous disorder and then in the meditative silence of being witnessed and reflected for who we are, for what we carry. In breakout rooms, we developed skits in Augusto Boal’s tradition of Forum Theater, surfacing the tensions we were grappling with and presenting them to the whole group for collective insight and problem-solving.

I felt as though we broke the patterns of dull, mind-numbing conference calls and webinars where we forget about our magical bodies, don’t make eye contact, don’t touch, don’t feel human or alive. Saxon reflects that we prioritized “the spirit of experimentation, collectively imagining different, out-of-the-box ways of being on Zoom. Ways we can humanize and reflect and coincide with each other even while physically separate—it’s amazing what’s possible.” One participant thanked us for “being so creative about how to bring life to this world of Zoom.”

I will be so alive it scares the doubt in me. – Tonya Ingram, poet and mental health advocate

I came to understand that I was not alone in my hunger for creative connection. For an outlet that touches a light inside of us, the divine, tender filaments of who and why we are. I have been able to integrate writing as a tool for healing, and for self- and community-care. With teachers and staff at the high school where I coordinate Restorative Justice, I held a few self-care creative writing spaces. I co-facilitated with my colleague David Maduli, who is also a DJ, and after welcoming everyone, we put on a musical track and allowed folks to write, simultaneously, in response to the prompt presented on the screen. You can hear Maduli recite his “impervious,” pandemic-era poem on the It’s Lit podcast, where artists discuss their creative defiance to the alienation of these times.

Much like in writing workshops I’ve done before the pandemic, there was an invitation to go inwards while still in the company of others. But with each of us logging in from our own private homes, it felt entirely different. We were all dealing with some form of alone-ness, in contrast to the frenzy of a typical school day where we have a million social interactions even before the first bell rings. The virtual writing space was one of chosen solitude, where we each opted into the introspective activity rather than being forced into it.

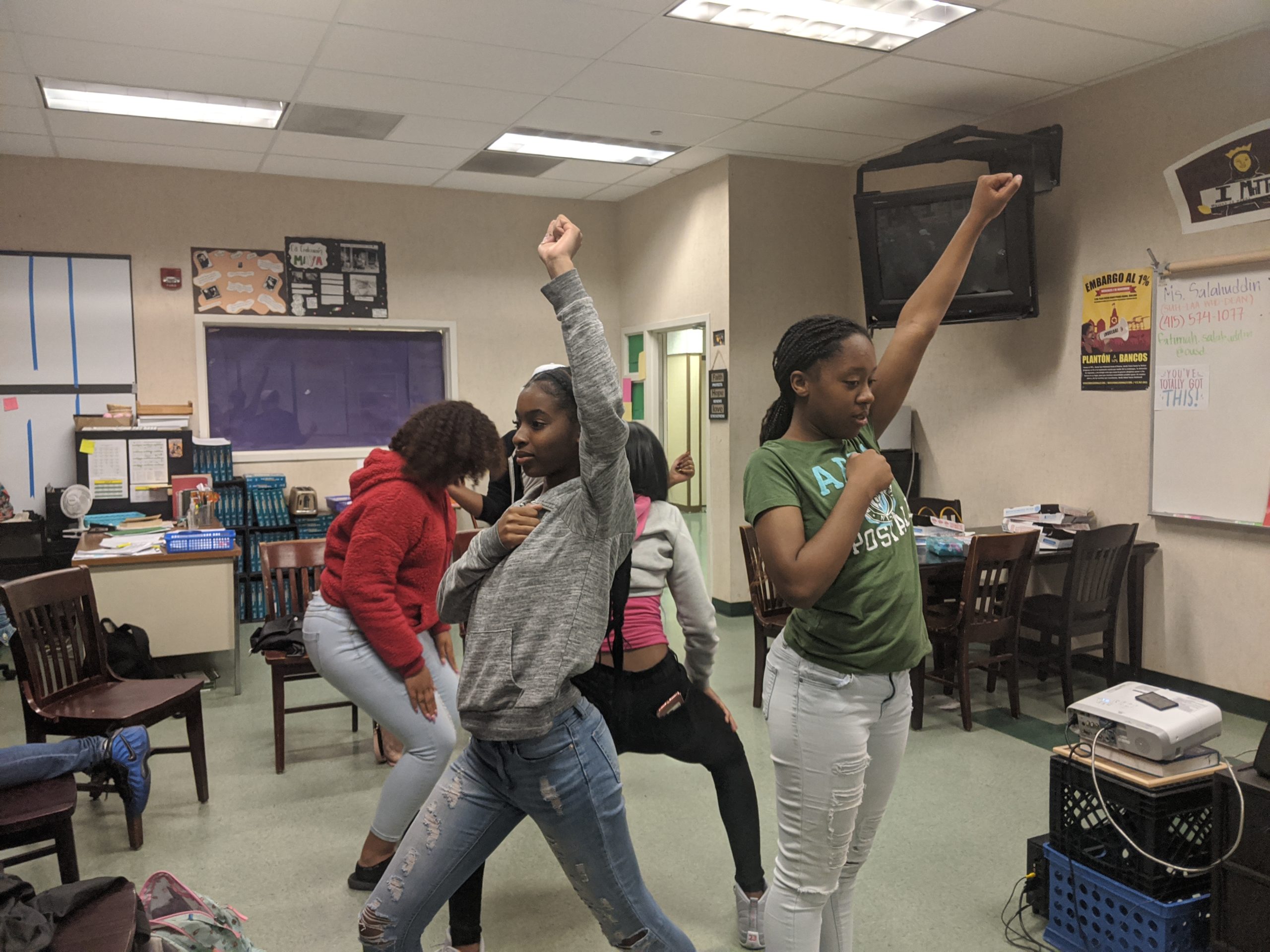

I followed this same format with the youth participatory action research (YPAR) group I co-facilitate with scholar-activist Fatimah Salahuddin. We work with self-identified Black girls to challenge the master narrative of urban youth in Oakland, supporting them to tell their own stories on their own terms, deepening their leadership and critical investigation of the world around them. Salahuddin’s favorite part has been “listening to their voices, especially since Black girls aren’t heard in many other spaces. It was empowering to hear them ‘name their pain’ as bell hooks eloquently says.” Before coronavirus, we used techniques from Theater of the Oppressed to unpack political and personal power. Moving to Zoom meant sacrificing the play and imagination we cultivated in person. The closest we got was through writing together with a backbeat and compelling prompt. The words that flowed are everything. They have sustained me.

Covid has pushed us into a mental health crisis, especially marginalized groups. It has felt like confinement, as we are trapped within the prisons of our minds and forced to learn new coping skills. It was a blessing, just being able to connect with these young ladies during a time when human connection was severed. After my classes went from 32 students to complete virtual ghosts, these meetings were the highlight of my week; it gave me purpose. The education system can run us down at times, causing teachers and staff to isolate themselves and resulting in us never collaborating. Tatiana has reminded me in a time of total and utter darkness of what is still possible when we set the intention and that sisterhood is powerful. — Fatimah Salahuddin

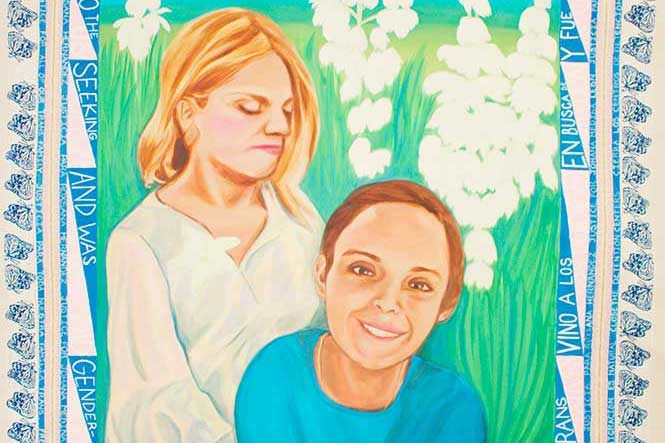

Writing is a salve, a channel to spirit. Art can be a spiritual practice, for self-sustenance and community uplift. Perhaps this is what matters, more than anything else. To give us the clarity and vision, the comfort, the sense of wonder that motivates us to keep going. I am reminded of one of my favorite portraits by Evan Bissell, featuring (then) youth poet Rena Stone, with her line: “writing should be a religion.” I feel this, deeply.

Performance Possibilities during Social Isolation: Overhaul + Redesign

I realized I had reached that light—transcendent, ecstatic—where everything comes together. The prayer I was building for ancestral healing, it was released. I was in my home, safe, able to design the performance the way I needed, and it created a beautiful vibration. —Mitali Purkayastha (GQMujra)

Parivar, translating to “family” from Hindi, Urdu, and many other South Asian languages, is a collective of trans and gender non-conforming South Asians in the Bay Area, with strong allies who are queer, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and intersex. It was through their Pride event, also part of APICC’s United States of Asian America Festival, that I was able to reimagine and positively reassociate what it means to perform during Covid. Intended to “celebrate our creative resilience together,” it featured performers and audience members from across international time zones, honoring our connection to homeland and challenging conventions of theater which otherwise restrict access to poor people and people with disabilities. An accidental gift, to recognize the exclusion that has existed among us, to grow our awareness. And, in response, to devise platforms that resist perpetuating harm.

I shared a comedic piece on my efforts to subvert the male gaze through eye gestures from classical Indian dance. Mitali Purkayastha performed what they call “Bolly-drag,” a mix of theater and dance from popular and folk genres, setting up their own space/stage with an altar and cultural artifacts. For Purkayastha, shelter-in-place coincided with a slower period of being alone, away from the classroom and co-operative housing for the first time in several years. “The privacy and stillness allowed me to call on spiritual guides, answering how my creativity can show up and be exposed.”

Interaction designer and new media artist Anum Awan’s journey through the pandemic has been analogous, corresponding with an intention for quiet reflection after a busy year of projects. One bright spot from the pandemic has been collaboration with people from across the world, as in Awan’s “Radical Technologists” meetup at the Allied Media Conference. As an audience member in the Parivar event, Awan commented that “the virtual format was really effective in integrating different mediums, with both pre-recorded and live performances.” They were struck by the patience and generosity that folks extended to each other in the face of technological hiccups and time delays, noting that “it felt really rejuvenating, a reminder of how much queer South Asian community is needed, now more than ever.”

The Zoom chat brimmed with love and affirmation for over two hours. I was amazed at how dynamically it conveyed support and appreciation to the performers, without interrupting them, similar to snapping in the slam poetry tradition. At a time when sadness seemed to be seeping in from all corners, for me, the communion at this event was powerful. Gave me a slice of hope, that we can gather as vulnerable and courageous individuals, a little less isolated from each other. That we can be responsive to injustice, and in this moment as accomplices in the movement for Black lives. Several artists and audience members had just completed Equality Labs’ online workshop series on challenging caste supremacy. After studying the interrelated poisons of anti-Blackness and anti-Dalitness, we were ready to take action, and the Parivar event provided a path that was rich in the culture of rebellion. Our cultural practices are the wellsprings for resistance, for dismantling casteist oppression in our own circles of trust.

Sejal Babaria co-founded SubDrift with me in 2018, an open mic by and for South Asians with shared principles of political solidarity. She says, “pre-pandemic I felt there was a lack of intentional artistic spaces for folks of South Asian descent, explicitly rooted in collective freedom, which is why we started Subcontinental Drift: East Bay. What was incredible in Parivar’s event was that along with coming together and sharing with such vulnerability, performers and participants alike were holding the space and one another with such care and compassion, while also leaning in to themes of inclusivity and liberation.”

In many ways, I feel that my artist-self has gone into hiding. I’ve spoken with friends who say theirs has outright died—consumed by extra care-work, loss of income, the unrelenting agony of this crisis. But when and where my creativity has emerged, I listen. To create art is to cleanse the soul, to find motivation, to untie the knots of confusion or despair, to intervene in the course of history. If I were to conceive of a participatory arts project now, in September 2020, I might return to my giant puppetry concept with Levana Saxon and attempt to activate folks around the upcoming election. Since the candidates themselves have failed to inspire—and in fact seem to be numbing us into voter suppression—their faces would be blank. We would fill them in with ideas from emails/tweets that folks send in about what they want, so that they are moving because of what matters to us, the people. I would choreograph a movement sequence to communicate that we are in control, compelling politicians to move by the strength of our core values. Hope is a slippery thing, but if art can magnetize us towards it, siphoning off the sorrow and despondence of these days, I’m there.