Mon July 7th Closed

Restorative Art from Communities Experiencing Incarceration

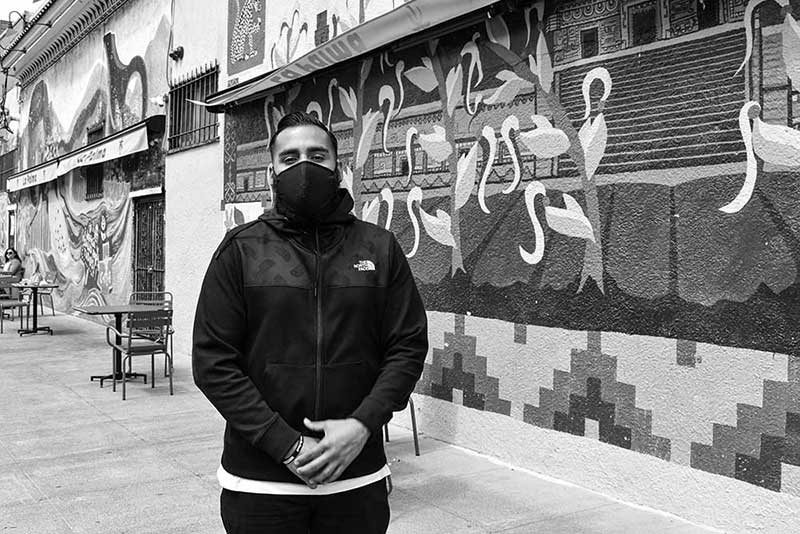

The 2019-2020 YBCA Public Participation Fellow cohort was originally gathered to collaborate and build on communities-based projects that demonstrated the mobilizing of public participation. However, as the Fellows worked on bringing their work to fruition, the world was hit with COVID-19. The cohort were then challenged to grapple with the question: what is public participation now?

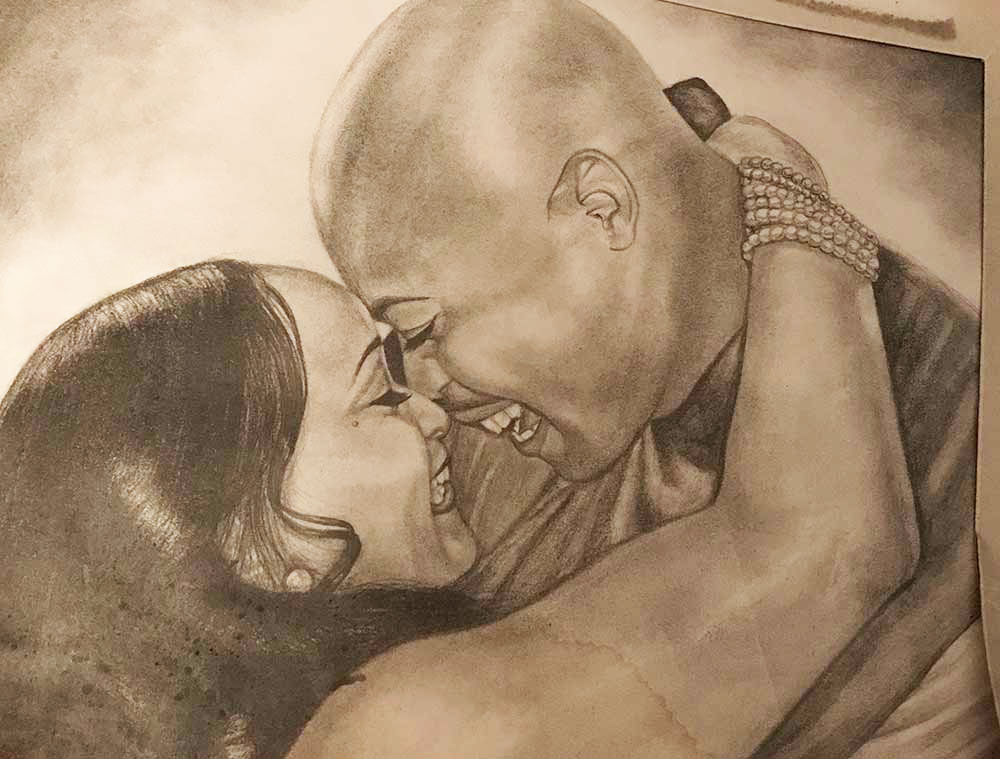

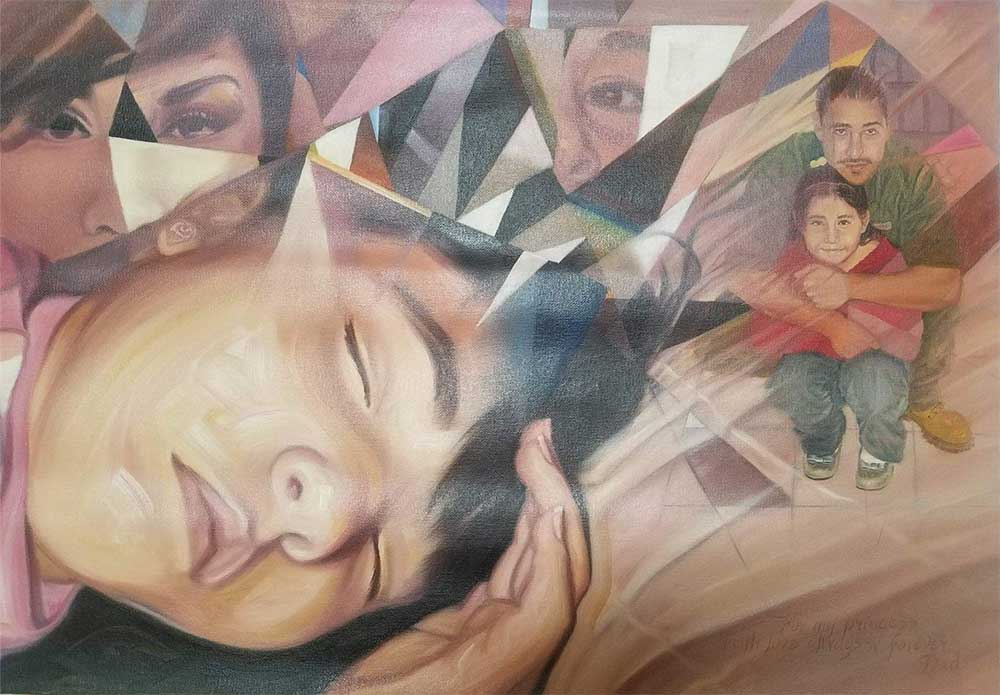

Ericka Scott married her husband Pride in 2014 at Solano State Prison, where he was incarcerated at the time. The wedding photographer, another inmate, took a beautiful, smiling shot of the couple. As a birthday present for Ericka in 2016, Pride commissioned a drawing from an older artist he’d met in prison. “When I saw the drawing, I just fell in love with it,” Ericka said. “The person who drew this needs to get exposure for his work.”

Through her husband, Ericka learned of a network of creators within the prison community. “Artists know artists,” said Pride, speaking about how incarcerated artists connect over a thriving business of customized greeting cards. “That’s how it spreads—word of mouth.” As he shared more pieces with her, she became determined to share the talent of these artists with the public.

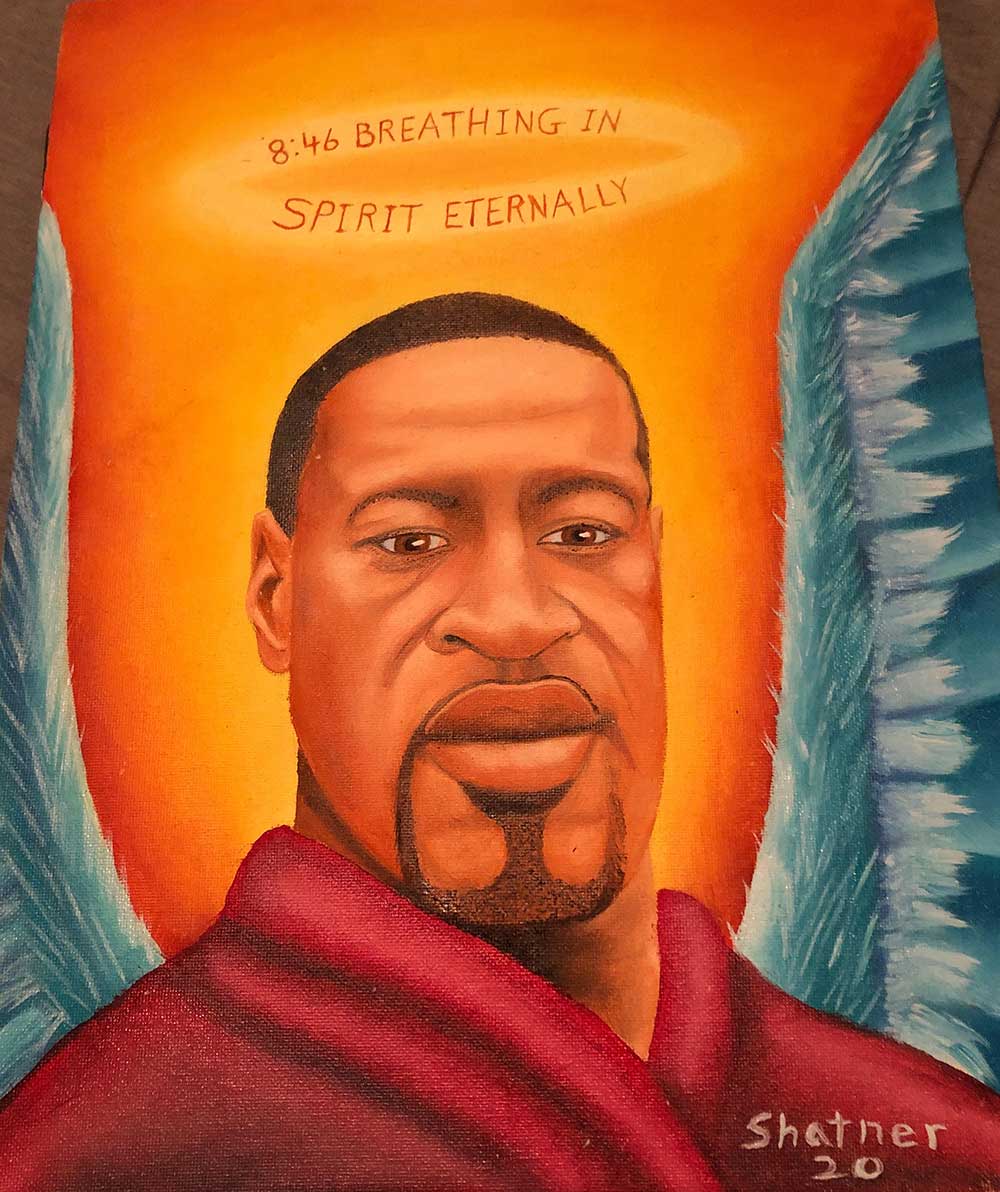

“With the stereotypes of people in prison, you’d think about all these hard core criminals,” she said. “But people just have so many different sides to them, and they connect through art. No matter who they are or what they look like.”

The Beauty Behind Bars project might have begun with one pencil sketch of a photograph, but Ericka is full of big ideas. Over the last 4 years, she has revised and expanded the project from an informal art sale to an online gallery to a pop-up installation in her own apartment. “The project itself speaks to a lot of people in my community, the Black and brown community, as it relates the trials and the challenges of what incarceration does for our families. For people who were ashamed and didn’t want to talk about their loved ones in prison, now they want to share their stories. They’re sending me pictures. The public participation piece is huge, especially being new in this arena, new to art.”

Ericka is a busy entrepreneur, teaching business development classes while also managing her business Honey Art Studio, which partners with the San Francisco Parks Alliance to offer weekly art experiences to Bayview and Fillmore residents in outdoor public spaces. Honey Art Studio also hosts art workshops and paint-and-sip art parties. An untrained artist herself, Ericka wanted to bring more art opportunities into her community, for youth and adults alike.

“There’s a huge social justice aspect to art,” she said. “I don’t think I had much exposure to art when I was a kid. I just didn’t have opportunities like my kids do now.”

After being accepted into the YBCA Fellowship, Ericka hoped to explore this idea of inmates’ artistic talents in combination with her passion for community art projects, before the COVID-19 pandemic and the Bay Area’s shelter-in-place orders derailed all plans. “Initially I wanted to get some of the inmates’ families together to work on some art that reminded us of our loved one who was incarcerated. I thought about doing a dual showcase—we would show the art that we produced, and then we would show the artwork from the artists who are in prison.”

“People just have so many different sides to them, and they connect through art. No matter who they are or what they look like.”

Thanks to discussions with other members of the 19-20 Fellows cohort, Ericka reimagined the scope and possibilities of her project. “Although we all have different projects, our common goal is all social justice issues and art. To have that kind of cohort is really unique, especially for me, since I’m not a trained artist. It’s given me a real appreciation for art.”

Ericka credits the support of the YBCA Fellowship both in putting the Beauty Behind Bars project together and giving her the ability to compensate the incarcerated artists for their work. “Having an idea and having a home for it is night and day. The resources are amazing, but just the fact that an organization cares about the issues we’re facing is incredible. To be part of an institution, especially one that has a program that wants to address some hard topics that people don’t want to talk about, it means a lot. I can make a difference, and I can get support to make that difference come to light.”

Ericka might be the project director for Beauty Behind Bars, but she credits her husband Pride as her project manager. Despite limited communication and socialization available in his current residence level 4 high-security prison, Pride Scott is a natural leader, bringing people together across racial and cultural lines. Pride is her man on the inside, she explained, recruiting artists, gathering art submissions, passing along information, and coordinating compensation for the contributors.

“That’s what I’m good at—putting people together,” Pride said. “I mainly just keep the artists motivated and let them know it’s really going to happen, that this is for real. They’re excited about having the public see their work. A lot of them, they’ve been down [in prison] so long, they don’t have any support in the street. Just the fact that the public can see their work and appreciate what they’re doing, It’s really special for them.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken the California prison system by storm, leading to huge internal reorganizations to comply with California social distancing guidelines and designate space for those who contract the virus. For those incarcerated folks like Pride, whose lives revolve around strict regulations and routine, the abrupt moves and changes within the system can be overwhelming. Ericka and many other family members of inmates never know when the next phone call from their loved one will come.

“It’s so difficult for us, not knowing day-to-day, just hoping that he’s going to be okay,” Ericka said. “And that the people who did contract it, we hope they’re going to receive the care they’re supposed to, but we all know that that’s not the case.”

Pride’s prison community has been on lockdown, with no hope of reprieve in sight. “We’re supposed to be practicing social distancing, but we don’t have enough space. They can’t afford it. A lot of people think it’s a hoax. But this thing is real in here. For us, we haven’t got the resources they’ve got on the street. The odds of beating it is rare. You either gon beat it, or you gon die.”

All of the art, reading, and educational programs—where inmates would normally socialize—are shut down. Pride had signed up to be part of an entrepreneurship program for incarcerated people, but it too has shut down. For Pride and the other artists, having the Beauty Behind Bars project to focus on during this time has been a big positive, Ericka said. “I didn’t realize it would bring such hope to people.”

Despite increasing limitations on communication due to the pandemic, Ericka feels that this project has brought her and Pride even closer together. “It hasn’t been that easy. You can’t count on next week or next month. Things change in there in a moment,” she said. But she knows she can count on him, even though they’re apart.

Ericka met Pride back in 1990, when she was in high school in San Francisco and he was studying at Bakersfield City College on a football scholarship. “I saw her at a Turkey Day championship football game, and I instantly fell for her,” said Pride. “Pride says that Bobby [my sister’s boyfriend] told him I wanted to meet him. Bobby told me that Pride wanted to meet me. You know, that kind of thing,” Ericka laughed about the set-up. “If you were to categorize both of them, you’d say Bobby was the good, stable guy, and Pride was the bad influence. And I happened to just fall head over heels for the bad influence.”

Pride struggled with the transition from San Francisco to college life, and ended up into some trouble that lost him his scholarship and landed him in jail, Ericka noted. By the time they crossed paths again, Pride was divorced, and Ericka had been a widow for five years following her first husband’s murder in 2004, when her two kids were small.

Pride reached out to Ericka through a mutual friend, wanting to know what he could do to support her. “I’m like, ‘How can you help me? You’re in prison!’” Ericka remembered. But she had mentioned that she was in the midst of moving, and the next day he sent some of his family members to come help. “He would always go the extra mile to make sure you had what you needed. I couldn’t help but appreciate that.”

Initially Ericka’s family was less than supportive of her renewed relationship with Pride. They didn’t understand how they were quietly developing their own family, across years and distance and prison walls, she said. “I think the fear is that getting together with someone who’s in prison is going to just drain you. Like you have to give them all of your money and all of your time. And that does happen. But that’s not the only story. The more my family talks to Pride, or they hear different things about him, they realize he really just wanted to be a support.”

“I love her drive,” said Pride. “She hears something, she thinks she can do it, and she’s off pursuing it. I support her ideas however I can.” He joked that he actually first proposed to Ericka back in 1993, but she turned him down because she didn’t think he was serious. “This time around, she knew I was serious. I was in Solano [State Prison], and we got married on a visiting day in 2014. My family got to be there and everything.”

What’s next for Ericka and Pride? She wants to support her kids as they start remote school, expand her business, and travel the world. “And I want Pride to come home, and feel like he’s in a safe and loving environment where he can really be the man that I know he can be.” She envisions expanding the Beauty Behind Bars project, adding written submissions or art from the families of the incarcerated artists, and even a video documentary of the project.

“It’s hard for people in here to really be seen and heard. That’s a big thing. Being seen and heard.”

“The YBCA Fellowship opened a lot of pathways for me, about how we can support the incarcerated community and bring awareness to who they are and what they’re working on,” Ericka said. “My goal now is to create a community where we can be more of a support for one another, not just a one time project.”

“It’s really important for people to feel like their work is valued, and they matter,” said Pride. “The people in here have ambitions and dreams, just like everyone else. That’s what I want the world to know about people in jail—the people who are in prison matter. It’s hard for people in here to really be seen and heard,” said Pride. “That’s a big thing. Being seen and heard.”