Tue July 8th Closed

Re-imagining the Future: A Conversation with Paola de la Calle

Paola de la Calle is a Colombian-American interdisciplinary artist whose work examines home, borders, identity, and nostalgia. Her practice is an exploration that ties together her family’s migration and personal memories along with historical and political narratives through the use of textiles, printmaking, and collage. As the Artist-in Residence at Galería de la Raza, de la Calle conceptualized and led the creation of the Uncage, Reunify, Heal Quilt Project, a public art commission for the Caravan for the Children Campaign in 2021, now on view at YBCA as part of the exhibition Pedagogy of Hope: Uncage, Reunify, Heal. A year after presenting the quilts in Washington D.C, Galería’s Executive Director, Ani Rivera; and Program Coordinator, Ivette Diaz ask de la Calle about her artistic process, the journey of community collaborations, and what she hopes for her art in the future.

Ivette Diaz: Let’s talk about the Uncage, Reunify, Heal Quilt Project. What was the seed that led you to conceptualize a project of this size? What was the process itself like?

Paola de la Calle: Before working on the Uncage, Reunify, Heal quilts, the largest artwork I’d ever created was a 6 x 24 ft installation. When I signed on to be the lead artist for the Caravan for the Children Campaign the idea for the quilts didn’t exist yet, let alone their size. The process of creating the quilts began with a lot of research. It was while sitting with the images of children wrapped in mylar blankets while laying on the ground of detention centers and getting teargassed at the US/Mexico border that the idea for the quilts started to unfold. When thinking of the call to uncage, reunify, and heal, for me it was important to combat the images we’re bombarded with on the news and invite folks to imagine alternate realities and a future where migrant children got to be children.

Ani Rivera: Most of your work embraces personal experiences and honoring cultural memory. Can you tell me how this gets addressed within the quilts? What parts of the work are personal? What parts of the work do you think are a larger conversation?

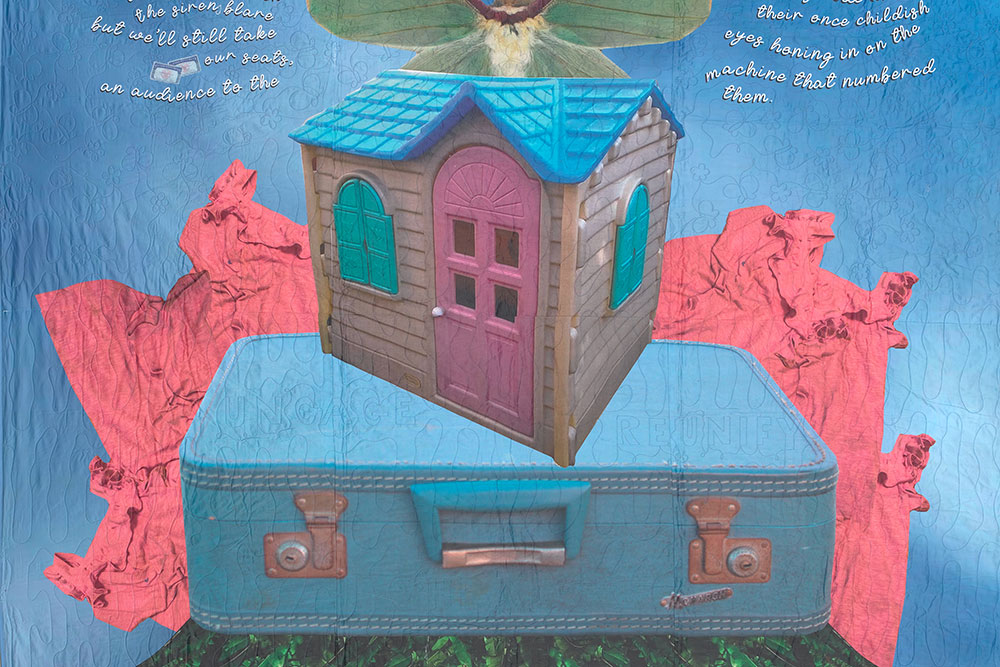

PC: There’s a plastic house that sits at the center of the Reunify/Reunificar quilt. That plastic house is the same house my sisters and I played in growing up, the same house that my Abuela Magog is sitting in front of in a photo from one of her visits to the United States. Being separated from family by borders created longing and grief, and home became a place in the liminal space between here and there. That plastic playhouse is an object that filled the distance between the US and Colombia. In that house I got to create imaginary worlds with my sisters. In my imagination, the house sat atop of a mountain in Colombia, in the neighborhoods where my parents cleaned houses, and in worlds created in our imagination. Bringing that image into the quilts was a personal choice because of its personal significance, however, the majority of the images in the quilts were chosen through the contributions from the poets who were selected to be part of the project.

ID: What images specifically called to you from the literary contributions that you thought were significant to weave into the story of the quilts?

PC: Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about Mica Miragliotta’s poem “Found Poem Text from Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli” where they write “But what else besides superstrings? to tie up the universe together”. This imagery brought the kites to life and the words from their poem became the strings on each kite in the Heal/Sanar quilt. Ruben Reyes Jr’s poem “December 11th, 1989” informed several images in the quilts. In his poem he writes:

“on this anniversary remember that our beginnings are

infinite laughter dark soft baby cheeks sunrise over the

horizon an uncle’s smile as he shucks corn so remember

that beauty is a seed as well and decomposing flesh

fertilizes flowers after half-a-dozen days in the hot sun”

The references to shucking corn can be found as corn husks on the Uncage/Liberar quilt which wrap themselves around the frames of the children like flower petals and the words “our beginnings are infinite laughter dark soft baby cheeks sunrise over the horizon” brought the large baby arms reaching out into the sky to life. I could go on and on, but I’ll end with Oswaldo Vargas’ poem “How to Tell A Border Story” where he writes: “We weren’t trained for when the sirens blare but we’ll still take our seats, an audience to the receding tide and their once-childish eyes honing in on the machine that numbered them.” This poem in particular illuminates the injustice migrant children face when they are forced to represent themselves in immigration court and is the reason there are social security cards sewed onto the Reunify/Reunificar quilt, as it refers to the ways in which migrant children are numbered. Before reading that poem there was a part of me that did not want to include references to papeles, papers, or images of the border as the campaign was pushing us to imagine an alternate future, however, Oswaldo’s poem was a reminder that the purpose of the campaign was to also confront our reality and the systems that got us here.

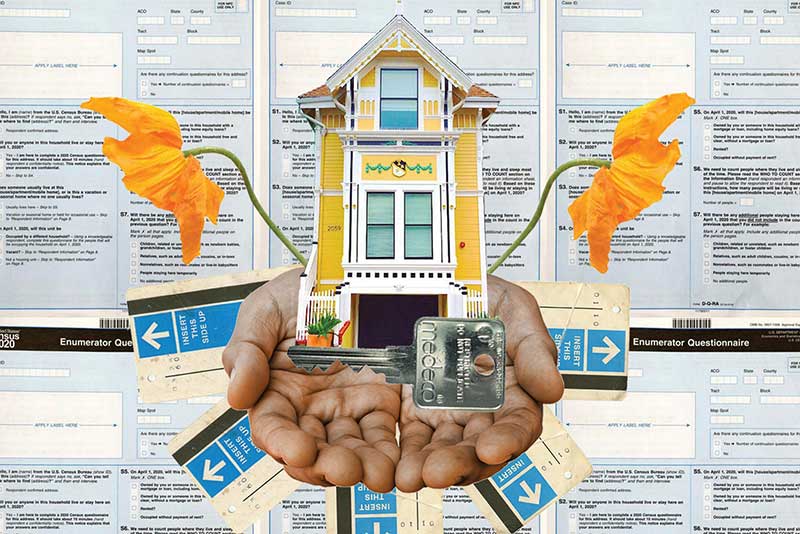

AR: In both the Quilt Project and the Census 2020 project El Futuro Es De Todos with YBCA, part of your process was to use external contributions or community conversations to inform the work. The Quilt Project used the work of poets, quilters, and seamstresses. The Census 2020 project used responses to questions you posed to the community online. How do you determine when community is essential to your process? How do you synthesize this information?

PC: In my work I explore notions of borders through a personal lens specific to my experience, that of my family’s, from a lens of memory, of being first generation, of Colombia and the US. Through that lens, I fill ruptures and draw links between the past and present. In some ways, that process of filling ruptures and drawing links is mimicked in my practice when working with the community. For the Quilt Project specifically, there were experiences I didn’t have, ruptures I couldn’t fill, and links I couldn’t draw. It was essential for me that other voices be included in the project, not only to fill those ruptures and provide varied perspectives, but because quiltmaking is a community practice. For me, the medium, material, and process need to be in conversation with one another. Historically, quilts have been used for storytelling and to recount narratives about identity and place. Drawing inspiration from the NAMES Project Aids Memorial Quilt and continuing in the tradition of quiltmaking as a community and storytelling practice bringing in various voices with varying relationships to the border in the form of poetry made the most sense as poetry also tells stories, expresses feelings, and creates new worlds through words.

AR: How does the collaborative approach with the community impact your work currently? Where do you see this approach taking your work in the future?

PC: During these past two years, I worked on two large-scale public art campaigns, the first resulted in a site-specific installation on 18th and Mission Street that collectively imagined alternate futures by reimagining the Census, the second resulted in the Uncage, Reunify, Heal Quilt Project. As the lead artist for both of these campaigns I was tasked with envisioning alternative ways to engage with the public during a period where gatherings were unsafe. It also presented the opportunity to reimagine how to co-create, make art more accessible, and collaborate across state lines. This period challenged me to move from creating work on social issues relevant to my own family history to engaging with and within the community to create public art campaigns and site specific public art installations. However, birthing those projects and putting them out into the world took a lot out of me. I am at a point in my practice where I would like to focus on an intimate body of work and turn the lens inward. Using Frida Kahlo and Gabriel Garcia-Marquez as sources of inspiration for this new direction I’ve begun taking self-portraits on a 35mm camera I inherited from my father and have begun painting on raw canvas with coffee.

“When thinking of the call to uncage, reunify, and heal, for me it was important to combat the images we’re bombarded with on the news and invite folks to imagine alternate realities and a future where migrant children got to be children.”

ID: In working with The Caravan campaign and a coalition of like-minded organizations to create art for a movement, what was your biggest takeaway? How would you like to see your work consumed, experienced, or utilized in the world?

PC: The quilts were initially created to be utilized for The Caravan for the Children Campaign, to be carried from the Homeland Security building in DC to the Capitol. The volunteers who helped us carry them and the folks who marched alongside us were the only people who were able to witness them until the exhibition opened at YBCA. However, their size, the intricacy of the threading, the poetry, and the meaning behind the images printed on the cotton require time to sit with each of the quilts. Like artwork for any movement I hope they are utilized and that more people can experience seeing them in person. Though the quilts aren’t being carried to the Capitol again, I’m excited to see them being utilized as the images for the postcards the Caravan delivered to the Biden administration.

AR: What about the more intimate work you will be creating? How do you hope it’s received in the world?

PC: I haven’t thought that far ahead yet. Because this work is coming from an intimate and vulnerable place (and is also still being developed) I’m hoping to learn through the process and be able to release the work into the world when I’ve moved through those feelings. However, I hope that this new direction, process, and these new materials are accepted as part of my practice and not a deviation from it. As an artist I want to continue to learn and grow with my practice, I want to be able to make shifts, experiment, and transform. I hope that people who enjoy the work I’ve made previously are curious about the shifts and changes I make over time as well.