Sat April 20th Open 11 AM–5 PM

Imagining a Collective Future

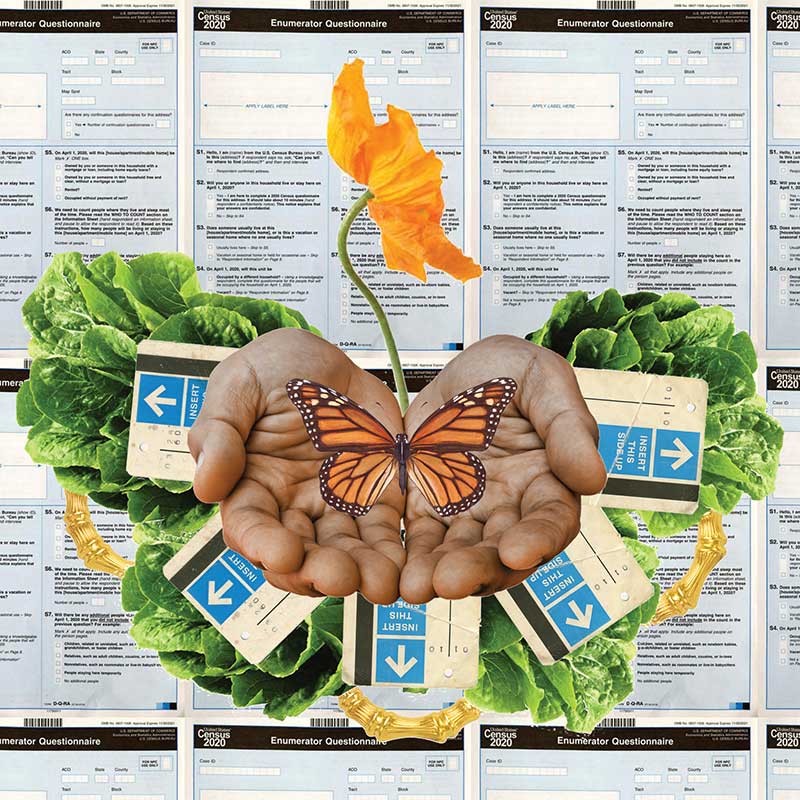

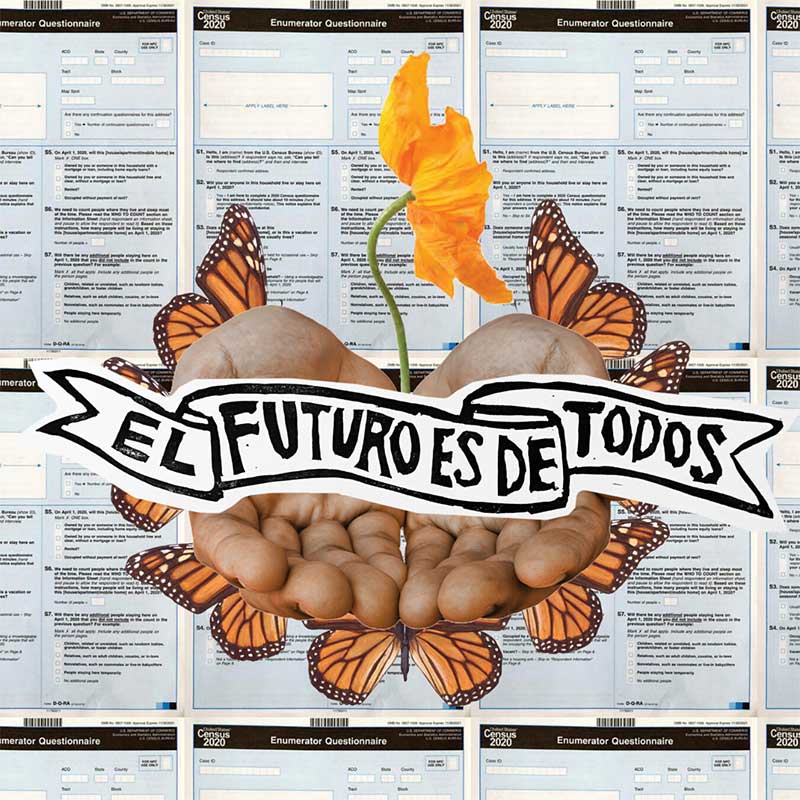

As part of our Civic Engagement program, YBCA has teamed up with Galería de la Raza and Artist-in-Residence Paola de la Calle to launch El Futuro Es De Todos, a localized 2020 campaign to encourage community participation in the 2020 Census. Galería de la Raza/Studio 24 is a non-profit community based arts organization founded by a group of Chicano artists and community activists in 1970. Galería’s “creative place keeping” ethos is rooted in social inclusion and justice, where community arts are central to navigating the complex intersection of urban development, social inequality, affordable housing and the historical-cultural legacies of communities of color.

Originally invited to be the teaching artist-in-residence at MLK Middle School, de la Calle worked closely with Galería and YBCA through the COVID-19 shelter-in-place, when an in-person program became no longer possible. During her residency, de la Calle created designs around issues at stake regarding the Census, including housing, public transportation, and healthcare. These posters became a social media campaign which posed questions to the public such as When you imagine the future, what do you see?, What does the future look, sound, smell, taste, and feel like?, and What do you wish the Census captured? What questions do you wish it asked instead?

The answers provided by the community informed the remaining poster designs that finished the statement “El Futuro Sera..” These posters will be printed to be displayed in windows or boarded up storefronts in select San Francisco neighborhoods, as well as circulated through community hubs that offer mutual aid resources for the community.

On August 5, 2020, Paola de la Calle, Galería de la Raza’s Executive Director Ani Rivera and Curatorial Program Coordinator Ivette Diaz sat down with YBCA’s Curatorial Project Manager Fiona Ball and Civic Engagement Manager Rebeka Rodriguez to discuss how public engagement can exist in a time of social distance and how to envision a sustainable and equitable future through Census participation.

Fiona Ball: Tell us about how you all came together through this artist residency program.

Ani Rivera: Galería de la Raza has always worked with artists to create a platform and a space that is responding to community visions, ideals, and aspirations towards the path to self determination. Artists have always crucially played a role, whether it’s through exhibition or on-the-go public art projects, to define how we see the future.

Our project first started as a way to extend our work into the school system pre-COVID times, with the goal of thinking about the next generation of youth leaders and making sure that art was accessible to them. After the pandemic hit and at the invitation of YBCA, we had a conversation to keep moving the project forward, understanding that in post-COVID, we still have issues that we’re dealing with and that artists really offer respite and healing and whimsy during these difficult times.

Giving artists a platform to offer solutions to our issues is really important and allows us to envision. So there’s also been on top of COVID, just general events that happened in our lives that we know we were planning already for, we were having the conversation around the census work and the importance of documenting and making sure our communities understanding how we provided an education in terms of informing what the census is. Given the political stand of the current administration, we felt that it was important to demystify and to provide education on why it is important to be counted, how does this inform and create opportunities of investment for the next 10 years? And so that being counted is important and yet thinking of ways to work with youth. They play a role into really informing families and so we were going to do that through the school system collaboration. COVID happened and we still felt we could touch on that and then some, so we’ve been shifting.

But really, how we started is that it’s not foreign, it’s in our DNA as an organization to work with artists and to celebrate their thoughts and to really make art as part of a human right and support it, that it’s accessible. And that it’s in the vernacular of their day to day, that it’s everywhere, it’s not just an isolated experience. And so, that’s what the artists residencies mean to us at Galería, it’s a natural extension of the conversations around the culture, equity and pride really. So I’ll leave it at that.

FB: Paola, I’d love to hear a little bit about your artistic practice, which appears very hybrid in nature. Could you expand a little bit on that?

Paola de la Calle: My work examines home borders, identity, and nostalgia. I previously only considered myself a printmaker, but over the course of time, in my exploration of various mediums and applying them to my practice what I’ve realized is that I’m an interdisciplinary artist and the mediums I use vary on the message of the artwork and what feels right in the moment both emotionally and in regards to the history of each medium. But at the core, regardless of the medium, I’m a visual storyteller with various intersecting identities and my practice is informed by that.

Because this project is one where we are engaging with the public who bring in diverse opinions and ideas for our collective future, the hybrid nature of my practice acts as a sort of reflection of these voices and our community.

When the shelter-in-place happened, we had to strategize about how we were going to shift the project. In that reimagining of the project I began to incorporate the digital collages with printmaking to meld together all of the different aspects of my practice. But even in that shift, it was important for me to incorporate printmaking and make it the center of the work, even while incorporating other mediums, because of the historical nature of printmaking as being a more accessible and democratic practice.

FB: Can you tell us a little bit about the content of the original project and how you pivoted it once the pandemic began?

PC: Initially, the project had a lot of different touch points with the community. We were imagining distributing things, having things sitting in public where people would have to actually physically touch the work. At one point we even considered having a sort of mailbox or newsstand people could pull print from, but obviously with COVID, that’s not something that would be safe for the community. So instead, the aspects of the project that had physical touch points with the community became melded in with the public dialogue, which then had to shift to be entirely virtual.

AR: So I think that’s part of the power of collaborating with an organization. It’s always allowing the space to pivot, to better serve communities. We’ve been very specific on who we’ve targeted as we think of COVID in terms of the messaging. As I mentioned earlier, as we’re seeing, we were going to use active storefronts as this poster to be the promotional material and to provide outreach. And now that we are seeing a lot of the storefront closures, commercial space closures, we’re using them actually as platforms, as some sort of exhibition and panel platforms. We’re also partnering with community-based organizations that can help share the message with those most impacted.

Where we really have created a partnership is with the work of the artists continuing to explore their practice, and allowing them to continue to produce during this time in safe settings. While we, as the organizations and first responders and activists find entry points to the community and to find them in a culturally specific and sensitive way. What I’m really interested in hearing from Paola, and more specifically is how this shelter-in-place has allowed her to still continue to practice. That’s where the hybrid of the traditional printmaking, and then the digital format has come to be one of her signature practices. So I’m wondering Paola, can you talk a little bit about the shift in that? Have you seen in COVID how this partnership has either shifted or supported or how you’ve adjusted to that?

PC: I think artists that I’ve talked to in general, that I’m in community with, have really been struggling to adjust. We’re not putting on exhibitions anymore. We’re not putting on public programs anymore. A lot of folks have lost their income as museums and other institutions are closing their doors. The way that we were used to being in community with each other has changed. So much of art is going up to it and seeing the texture, being able to be in conversation with someone who’s looking at the same piece as you. And those aspects don’t really exist anymore, as much as we’ve tried to make them go virtual.

But I also know that another side of that is the practice, right? And as an artist, I’m used to making work by myself, I’m used to being in isolation. I actually thrive when I have hours and hours to myself when I’m locked in my house, my studio. But what the shelter-in-place order really did was allow me the time and space to incorporate play into my practice, to set up an actual studio space in my house. My studio used to be the living room floor which I had to clear out otherwise my roommates would get upset, but now I have a dedicated workspace where I can leave materials out and return to them the next day.

This project and Galería have provided me a platform to engage with the community as we all are apart from one another. For me it can be difficult to respond to events that are happening as they’re happening without allowing myself some time for reflection and this project has provided me a space for that. It’s allowed us to look at the way that, one, COVID has disproportionately impacted poor, Black, POC, low income and migrant communities. This project has allowed us to have a specific lens in which we’re looking at the Census, who we want to be in community with, and also provide a space to not just sit in reflection, but really imagine what a future looks like. When we get to imagine what the future looks like, what we’re saying is, we’re here, we exist, and we exist in the future too. What would it look like for us to be in a place where we’re not under resourced or we’re not under funded? Where equality exists in education, where all people are fed, etc.

So for me, Galería and YBCA have provided the space to be able to engage with what’s going on right now artistically and to push through beyond this moment and look towards the future with the community.

FB: You mentioned the future and I noticed that with your project, you’re posing a lot of questions to the public to create this kind of virtual engagement. You’re asking folks, what does the future look, smell, taste, and feel like? And what do you wish the census had captured? How did you develop these questions and what kind of public engagement are you hoping to create through this kind of interactive element of the piece?

AR: I mean, I’ll speak from our organizational perspective by saying we’ve always been a place to respond to, to really sit with these thoughts and ideas because they’ll eventually become the values of how we present and create and engage with the community. So we started the conversation understanding the isolation. So we said, well, what if the Census has more than just asking the nine questions. When you go through the questions, they’re kind of cold, I don’t think they really capture the human essence and how it could really articulate what is needed in our communities.

We wanted to change the framework, this is a moment and for us to dream and to really think beyond more than just housing for instance. Do we just need housing, like a brick and mortar structure, or do we need it to have a holistic approach for who we are as people? How do we articulate that? We wanted to go a little deeper into what was really in people’s minds and hearts around how they see their future.

In the midst of talking about the Census, COVID-19 came, and then the real opportunity came to capture and get different perspectives from the call for racial and social justice through the death of George George Floyd. And we really started seeing that what we are calling for in terms of the Census, is aligned with the Black Lives Matter ask. We want to disinvest in police and the militarization of our people. We want to make sure that our people have access, equitable access, to housing, education, health, and transportation. It’s all aligned. We’ve been going around in circles, like what’s in our hearts, what’s in our minds, what would it look like? But at the end of the day, it was really like, this is an opportunity for us to call for justice.

And so it took two approaches. We put a stop and we said, we cannot move forward. Even with understanding the Census and how it relates to what the call of social justice and racial justice means at this moment, because we’ve been part of the same conversations. Galería has been doing work around calling out to the end ICE, calling to immigration, not even reform but just a path for citizenship, for the 11 million people that are in limbo. It is all connected. I felt like it was also a moment from an organization to say, we need to connect the dots for our community if they’re not doing so and how do we create a conversation around that?

“We’re here, we exist, and we exist in the future too.”

We cannot ignore one without the other. Now that the current administration is trying to stop certain folks from completing the Census. I mean, that just to me is ludacris—it is to control Black and brown bodies. The future has to be what we wanted to call it out and what we wanted to see, feel. We have been engaging in that conversation, and what we hear is all connected to a reality that is doable.

If we think about how we control investment in our community and understand the process of advocacy and policy and what the Census is, the question that Paola is posing is not far fetched. And actually that’s how we should be doing it, healing and envisioning together. I feel like other projects ask us to just complete the Census, but there’s something about getting to the core of why it is important and how it’s going to allow us to show up wholeheartedly.

PC: For me, the role of the artist is to contextualize the census in a way where it doesn’t feel like this foreign document where you’re just dumping all your personal information. I grew up in a mixed status family. So my parents, my immediate caretakers, were undocumented. My siblings were undocumented. And that, for me, when being presented the idea to work on a project about the Census, kind of brought the question of, why me? But it’s important for people like me or who grew up in similar situations to recognize how important the Census is, even in it’s flawed form, as this document that can provide resources to our communities.

For me, it was about being able to think back on,whether my parents even completed the Census and why didn’t they? Because there’s fear attached to completing these kinds of forms. So when we remove these questions we can maybe imagine this document in another form that instead focuses on the things that are important to you, or gives you space to call out the things that you see are lacking.

I think that that’s where the questions developed from. Especially the one of, when you imagine your future, what do you see? What do you feel? What do you taste? What do you smell? Maybe those things don’t seem important, right? What do you smell? But it is important especially, if you live in a place where there’s a garbage dump or there’s high pollution from factories right next door. If you have the potential to impact the way that the outside of your home smells, why not try to imagine that? And why not try to see how maybe this document, and by just simply completing it, could help us work towards a future where that’s healthier.

Ivette Diaz: We’ve also seen how the questions are an opportunity for people to open up on how they feel about their communities, and really, we just uplift their voices. We asked the question, what questions do you wish the census asked instead? Many responses wanted to see questions that asked about what our community prioritizes in terms of programs and what programs are lacking, what languages we speak in the home, questions that asked about access to affordable and high quality food or grocery stores. People just want to feel represented and seen, like their input truly does matter, and not just seen as a check box on a form, you know?

FB: How has this public dialogue influenced your practice? Do you see any changes in the way that you’re making work by being part of this conversation?

PC: As an artist and a person, I am obviously in my head a lot. When thinking about this project and creating the initial images so that we could start the public engagement, I obviously had my ideas about what those images were going to look like. One of the images is called “An Offering for the Future” (2020), and there’s a monarch butterfly at the center of it, which can mean a lot of different things. It can mean transformation, it can mean migration. As I’ve started to look at the messages that people are sending, the questions that people are posing, I’ve seen so many different interpretations. What it’s done is opened a brand new world of possibilities, because I can’t be the voice for the future, that’s for all of us. But as people start to contribute, my role is now to transform these words into visual depictions of what we see for the future.

FB: This project is really a multi step process, right? You put out the call on social media, you get the responses, and then you’re creating these posters based on the public dialogue that’s been created. Why is it important for you to have both the virtual element of the project and the physical, with the responsive posters?

AR: I want to break that down from our perspective, Galería la Raza. The poster printmaking project was always at the center of what the intent one, even before the COVID crisis when we were talking to the school. We wanted to continue to honor that historical practice which is very rooted to Galería’s history. Galería started cultivating Latino artistic leadership and incubation in the ’70s when it started creating its calendar series where it would commission artists.

And it was that series that created the plethora of Chicano poster-making that was tracking a conversation of the Chicano movement. It was really connected to political printmaking historically. It’s been utilized worldwide, but for that time period when the Galería was founded, it was really a way to document what was happening.

I think our communities, the Latinx communities, whether we come from Mexico, Central America, South America, the Caribbean, printmaking has always been connected to politically organizing. Artists are at the center of a conversation, creating visual iconography that can replace sometimes words if you’re dealing with our communities that are, like we said, monolingual. Some folks in our communities don’t read and so visual iconography has always been important to organize people where we come from.

I also want to acknowledge that that is something we wanted to do with the youth. We have to give them the experience of being close to printmaking, to understanding what that is because it’s connected to a history and our identity as an institution.

By going virtual, we have to acknowledge that access to technology is a barrier. I’m not going to say it isn’t, but honestly, our people are connected. Our people have Facebook. Our people have WhatsApp. Our people have Instagram. They are connected. So even though we tend to create this narrative that our poor people, they’re not connected, our poor people… No, they’re very connected. They’re talking to their families across borders and visual iconography continues to be seen on our social media.

We always create work in the sense of the vein of, if your grandmother doesn’t understand it, then you’re really not doing it right. When we look at the work that Paola is doing, it really does connect the bigger picture. You understand what a home is, you understand what a beautiful flower environment garden means, you understand getting a BART ticket. It’s really trying to follow in that historical printmaking value and leaving room for growth and for contemporary translation.

We’re also not just part of one community. And going digital allows us to share our platform with other partner organizations, like the Mission Economic Development Agency, which does economic advocacy and work in the mission. We’re using their platform, not only on social media to promote the Census conversation, but to also be on the ground and where they have storefronts, to center the conversation.

“Change has to include artists at the center always, from the development.”

FB: Is there anything else about the project you’d like to share?

AR: We talked a lot about Galería’s role as the connector, but I do think we’ve got to talk about just, the project is in partnership with YBCA, and then we have partners in terms of the media campaign. Right now, these types of projects and collaborations are what is going to keep our people informed and provide accessibility. What I would like to see as a next phase for the project is a more regional Bay Area approach, because we’re focusing on the city right now, which is our priority, but I want to acknowledge that I think we are a transient city that depends on the workforce and labor on a regional level around those most impacted.

PC: Thank you for that, Ani. I think the one thing, and this may just be context for us to think about, is really that the ecosystem that supports the artists is made up of a lot of not even just different types of arts organizations, but lots of different types of organizations, institutions, people. And when we think about imagining a healthy collective future, it does take the relationships of so many different people in so many different organizations in order to provide support for working artists, for connection between arts organizations, and for education and inspiration for people whose future depends on this one piece of administrative process.

AR: And to the world, make sure that in your vision of solutions you invest in the arts because artists are the ones that can articulate those thoughts and values. This is a moment that we have to really shift the paradigm, and art should be at the center of how we think of our community development strategies and visions. It can not be without culturally specific investment. Change has to include artists at the center always, from the development. I think this moment that we’re in, I’m calling it a reset, pre-development of what we want to see post-COVID. We don’t have to go back to the status quo because we’ve clearly realized that the system was broken and not working for us. So invest in arts a hundred percent.

FB: Yes. Snaps to that.

AR: Make a question on the Census about arts, that’s what I would like to see.