Tue July 15th Closed

Songs of Resistance and Solidarity

The 2019-2020 YBCA Public Participation Fellow cohort was originally gathered to collaborate and build on communities-based projects that demonstrated the mobilizing of public participation. However, as the Fellows worked on bringing their work to fruition, the world was hit with COVID-19. The cohort were then challenged to grapple with the question: what is public participation now.

For nearly four decades, a body of Jon Jang’s music works represents a chronology of Chinese American history in San Francisco such as Island: The Immigrant Suite No. 2 for the Kronos Quartet and a Cantonese opera singer. As the grandson and son of undocumented Chinese immigrants (“paper sons”), Jang’s music gives a voice to a history that has been silent. For his fellowship at YBCA, Jang produced the new concert with conversation program “So Many Tears” with musicians Marcus Shelby, Francis Wong and poet performer Genny Lim. Referenced from the title of Tupac Shakur’s work in 1995, this program responds to the recent legal lynching’s of Black American citizens by the police, as well as to the rise of anti-Asian American violence caused by President Trump’s racist rhetoric around the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jang sat down with YBCA Curatorial Manager Fiona Ball on August 4, 2020 to discuss his experience as a YBCA Fellow, the many pivots his project was forced to take, and a brief history of Asian American and Black political solidarity through music.

Fiona Ball: Tell me a little bit about how you learned about the YBCA fellowship and what or who inspired you to apply.

Jon Jang: Well to be honest with you, I plunged into the water with my eyes closed. I didn’t talk with any colleagues or peers. I just applied, and then I was surprised when I saw that I was probably the only one that’s over 50 years old. [Laughs] So I really didn’t have any expectations, but I was curious. I wanted to connect with younger artists and younger change makers.

FB: Originally, the fellowship’s theme was looking at how to mobilize and uplift communities. How did you originally interpret that theme?

JJ: It’s about the role and impact of artists in building communities, and that’s been part of my work for the past four decades. I have my feet in many different communities of color. I used to be a member, and a hardcore activist, in an organization called the League of Revolutionary Struggle, which was made up of multiple organizations that merged to form one organization. Organizations that came together ranged from hardcore activists from the Black Liberation Movement, the Chicano National Movement, and the Asian American Movement, as well as white progressive activists.

FB: And then what was your original project for the fellowship?

JJ: The original project idea in the summer was to give a presentation called “One Day American, One Day Alien: Black and Brown Artists Who Made the National Anthem Their Own.” I gave talks about this topic at a number of universities and colleges. It’s about the history of controversial interpretations of “The Star-Spangled Banner” by black and brown artists, such as José Feliciano, when he sang the song in Detroit at a 1968 World Series baseball game. José Feliciano was a 23-year-old blind Puerto Rican singer-songwriter and after he performed it in English, baseball fans were outraged because he did not sing it strictly to what was written and Feliciano was a Latino, not a white man. Like singing all of his songs, José Feliciano sang it like José Feliciano sang it, freely and soulfully with his guitar strumming accompaniment. As a result, radio stations banned airplay of his recordings.

Then there’s Marvin Gaye’s performance at the NBA All-Star game in Los Angeles in 1983. He was attacked because of his sensual rendering of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” but in that same month of February 1983, his record “Sexual Healing” was lauded by the American Music Awards and the Grammy’s. Notice that these controversial performances took place in particular settings, such as either political events or sporting events. If we examine Jimi Hendrix’s performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the Woodstock Music Festival in 1969, it was at a music concert, so it wasn’t considered controversial.

Going back to the first question you asked about how can we uplift our public participation, back in the late 80s or early 90s I was thinking about civic participation and I proposed a project called “SenseUS”. It’s spelled SenseUS to mean sense us, that is, sense people of color and sense the United States. What’s remarkable about this piece is it speaks to today about trying to empower voters of color to vote. This was an expression of inclusion and also celebrating our history.

This collaboration featured Max Roach, John Santos, the three of us musicians and three poets: Sonia Sanchez, Victor Hernandez Cruz and Genny Lim. The idea was we did not want to reinterpret the national anthem, we wanted to reconceptualize it. Why is there only one anthem? Does one anthem speak to all of us? Why does the anthem have to be a song?

FB: And then fast-forward to today, you obviously had to pivot your original planned fellowship project first with the COVID-19 pandemic, then again after the murder of George Floyd and many others. Can you walk us through a little bit how you responded to both pivots and how did we end up at the program “So Many Tears”?

JJ: In the discussion with the fellows, we were talking about how we could connect our project with our communities. For me, I have a lot of community building experience with San Francisco Chinatown. I was the unofficial composer-in-residence of the Chinatown Music Festival for eight years. I would always premiere a new work that celebrated Chinese-American transnational history. With the original project “One Day American, One Day Alien: Black and Brown Artists Who Made the National Anthem Their Own”, it seemed kind of awkward and out of place that an Asian-American would be giving a presentation about Black and brown artists, especially if I gave it within the San Francisco Chinatown community, and it would be difficult for me to give this presentation in the Black and/or brown communities. This is related to why Marcus Shelby was added to the YBCA’s project “So Many Tears” to really salvage it.

Then I was interviewed by Downbeat magazine, which is a prominent jazz trade magazine. The interview was about the impact that the coronavirus had on Asian-Americans. This interview was about the rise of anti-Asian violence after President Trump and his Republican Party actors started to rename the coronavirus with the racist references toward China. They repeatedly rename the coronavirus the China Virus or Kung Flu. I was interviewed by Downbeat, and I thought, “This is an important issue for Asian-Americans and particularly Chinese-Americans, and this would be a project that would engage the San Francisco Chinatown community.”

This was a great opportunity, but then the torture and legal lynching of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police occurred followed by large protests all over the nation.

During the 1970s, Asian-Americans, particularly Japanese-Americans, Chinese-Americans, Filipinos and to a lesser extent Korean-Americans, developed a political consciousness inspired by the Black Liberation Movement and the Civil Rights Movement, which led to the birth of the Asian-American movement in 1969. I grew up in Palo Alto, raised by a single working class mother, and I also had an older brother and younger sister. At that time, Palo Alto was predominantly white middle-class. During my high school years in the early 70s, there was a bookstore called Chimera Bookstore. I read these life-changing books and recordings about Black arts music of resistance and Black revolutionary politics. One life changing book was Leroi Jones’ Blues People. After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Leroi Jones rejected his slave name and changed it to Amiri Baraka and became the father of the Black Arts Movement, as well as one of the important voices in the Black Liberation Movement. There’s a great video sample that I show people from Def Poetry Slam. It’s called “Why is We Americans?” By Amiri Baraka.

FB: And did these works inform “So Many Tears?” Are they references throughout the work? How do they all relate?

JJ: I think, simply put, and it’s a term that I learned from Amiri Baraka, but I think it’s a part of the Black music continuum. History repeats itself, and I have a lot of work that commemorates Black Lives Matter or commemorates Black victims. One of my early works was called “Eleanor Bumpurs.” Eleanor Bumpurs was a 66-year-old black grandmother who was murdered by the police for not paying her rent on time. This was in 1984 in the Bronx, New York.

FB: How do you feel like this program, considering it was really finished in a time of social distancing, how do you think it contributes to public participation or speaks about it? Where do you see the relationship?

JJ: Well, I feel it is part of my continued role in building Black-Asian solidarity. I guess that’s a simple answer.

In 1993, I was commissioned by Cal Performances to compose what we called “Color of Reality” and this piece pays homage to victims that are people of color. Some people it addressed included Leonard Peltier, a Native American who was a political prisoner, and still is a political prisoner; Eleanor Bumpurs, the 66-year-old Black grandmother who was murdered by the police in the Bronx for not paying her rent on time; and Vincent Chin, the 27-year-old Chinese-American who was beat to death by two drunken white men and made a scapegoat for the anti-Japanese import hysteria in Detroit. The two white men were exonerated. That was part of the rise of anti-Asian violence, which is repeated today with the coronavirus being named the Chinese Virus and Kung Flu by Trump and his Republican Party actors. Then the fourth and final victim, Rodney King, a young Black man who was beaten 56 times by the Los Angeles Police, and the police were exonerated. They were not punished, but also during that time a Korean merchant killed Latasha Harlins for buying orange juice. The Korean merchant’s punishment was basically a slap on the wrist.

The media depicted this struggle as like a Black-Korean tension, so my work is trying to build the Black-Asian solidarity through music and also as a public intellectual. Part of it is that I have to learn about Black history as well as Asian-American history. That’s something that’s, I think, since the 1960s comes in different forms, different contexts, different generations. My generation of Asian-American activists were mainly Japanese-Americans, Chinese-Americans, Filipino-Americans, and Korean-Americans. Since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, our population has become more complicated and more diverse. In fact there’s a Bay Area organization called Asian for Black Lives Matter made up of Thai, Burmese, Filipino, Thai and more. So there’s a great inclusion of Southeast Asians as well as South Asians.

It’s also important to remember some of these families are multi-generational. You might have grandparents, parents and the young activists living in the same house, and those who immigrated here might not know U.S. history except maybe through the lens of a white perspective which is part of watered down history. That of course is part of white America’s practice of erasure to “white out” the history of people of color to sanitize the insanity.

FB: Do you have any other closing remarks that you wanted to share with the YBCA audience about the piece or about your experience as a fellow?

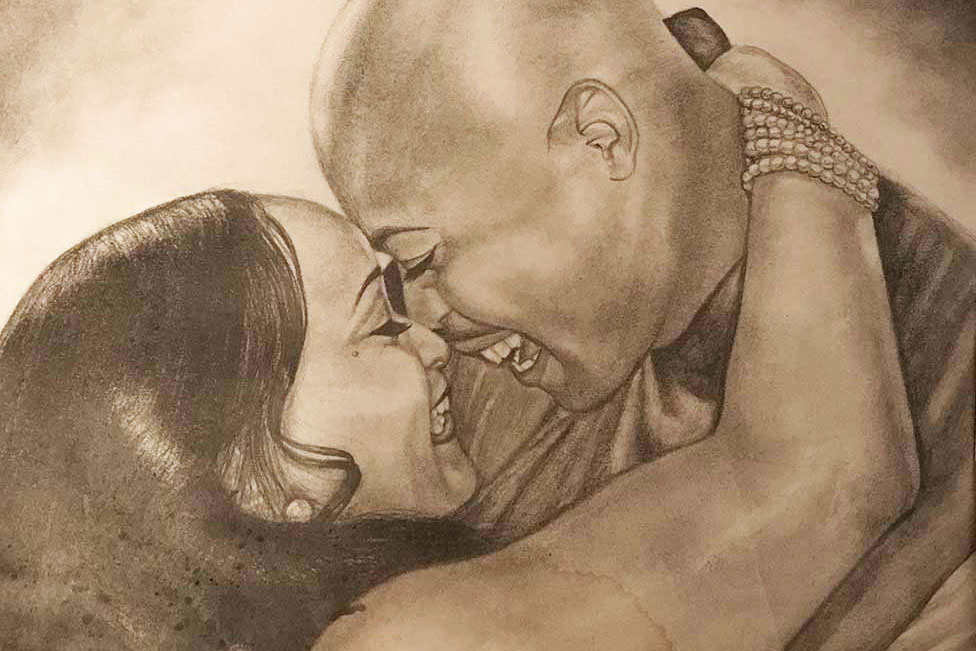

JJ: Well “So Many Tears” is a reference to Tupac Shakur’s composition from 1995. I was commissioned by the San Francisco Arts Commission Individual Artist Commission program to compose a work called “Can’t Stop Crying for America: Black Lives Matter!”, so those works are on my latest CD “The Pledge of Black-Asian Allegiance.” You can also get the music on Soundcloud as well as Bandwidth. So there’s this metaphor in my work about tears. Right now I think we’re grieving with this crisis that Black people have survived and endured for four centuries. As a human being, as a person of color, as an Asian-American, we should support H.R.40, the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African American Act. Because we have systemic racism, we need to make systemic change. I think part of “So Many Tears” was that we explore the histories of our peoples to make systemic change.

Like for Chinese immigrants in America, White America has feared that we were carriers of the deadliest diseases. In 1900, the San Francisco Board of Health created this deliberate scare to blame the Chinese for the Bubonic Plague to get rid of the Chinese and burn down Chinatown. When in fact, no Chinese got the Bubonic Plague. That’s the kind of history we need to look at as well as with Black people. We have to remember that lynching wasn’t just a mob of hateful white people. It was also a social activity where people would go outdoors under picnic settings, and they would pick a Black person and lie that he stole something or looked at white woman as an excuse to torture that Black person, castrate him, burn him and save severed body parts as souvenirs. When I’m performing this music, I feel uncomfortable. I think we have to learn to be uncomfortable to talk and learn about our histories. That’s pretty difficult.

One of the lessons I learned from Bernice Johnson Reagan is that building Black-Asian solidarity takes time, patience, trust, discomfort, and troubled love. It doesn’t happen magically like the song that I detest called “We Are the World”. If one is a non-Black person who wants to support the Black community, one has to learn to listen to the voices of the Black community rather than what you think.