Thu July 10th Open 11 AM–5 PM

Empowering Future Generations with Teaching Artist Fred Alvarado

Earlier this year, YBCA answered Mayor London Breed’s call to support students with high levels of need in the many challenges they face amidst the COVID-19 health crisis. Our galleries transformed into Community Hubs for social distancing learning, providing safe educational support for students at Bessie Carmichael Elementary. As part of their time at the Community Hub, students worked with YBCA Teaching Artists to engage with crucial arts education and build creative skills alongside one another.

On December 4, 2020, Civic Engagement Manager Rebeka Rodriguez sat down with YBCA Teaching Artists Fred Alvarado to discuss how he and his students have found opportunities to connect and learn in the Community Hub. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Rebeka Rodriguez: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me today, Fred. Let’s start out with some introductory questions: Who are you as an artist? What is your art practice? And what is your relationship to Bessie [Carmichael Elementary School]?

Fred Alvarado: Hi, my name is Fred Alvarado. I’m an artist, a teacher, and an activist. I work in different community settings, centers, and schools throughout different neighborhoods in the Bay Area. I’ve been working with Bessie Carmichael Elementary School for the last six or seven years. I teach basic drawing to students in the third, fourth, and fifth-grade with an emphasis on creating public projects that intermingle with everyday settings.

RR: Tell me a little bit about the work that you’re doing right now with Bessie Carmichael students in the Hub, and how that compares to the workshop sessions with students at Bessie Carmichael pre-COVID.

FA: With each classroom, I typically teach nine classes. I communicate and collaborate with the teacher to provide beginning art classes. We usually focus on drawing, and painting using watercolor, pencils, markers, acrylic paint, pastels, and different kinds of papers. That’s how we kind of set a foundation. We start off with the basics and we work towards a collaborative project with every classroom in all three grades.

For example, in the past, each class has created a mural on a portable surface that we installed in the library. We even installed murals in the cafeteria. We’ve worked on a series of posters with Rebeka and YBCA, and with a whole bunch of different organizations within the community. It was called We Walk Here. We created murals which became posters, and the posters were then distributed to different organizations, shops, grocery stores in the vicinity of the school, which is about 12 city blocks squared. It goes up and down Seventh Street all the way past Market, and it goes either direction. So, the kids could see their artwork right where they live and other people could see that they’re existing in the heart of the city.

We also made mosaics. One was a project where we made stepping stones for the Tenderloin People’s Garden, where they give free vegetables to people from the community where the students belong. Over three years, the students created murals for the garden; created stepping stones for the garden out of mosaics; and created sign placements—signs for each of the vegetables that they grow there.

RR: How did you have to change your curriculum or your approach to working with the students with all the necessary COVID safety precautions?

FA: Well, I think we didn’t change too much, to be honest. What did change was the site. The students that I’m working with now were in need of a space to do their schooling because of different issues. They didn’t have a space to concentrate and do their studies. So, the city, DCYF [Department of Children, Youth, and their Families], Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and Mission Graduates teamed up to create a hub to learn at YBCA. The physical space changed, and instead of working with all nine classes, I’m kind of working with representatives from each grade. I have two third-graders, two fourth-graders, and two fifth-graders, or something like that. So, I have an even number of each grade, but it’s a smaller portion, going down from 160 students to seven students.

The space itself kind of dictated how I went about planning our class. I really wanted to highlight the space that we’re in. And kind of out of some strange luck, the privilege of hanging out in a world-class art center, and seeing the hustle and bustle of it every day, is very interesting. I wanted to just pull that out for the students to see. I wanted to have them kind of feel the experience.

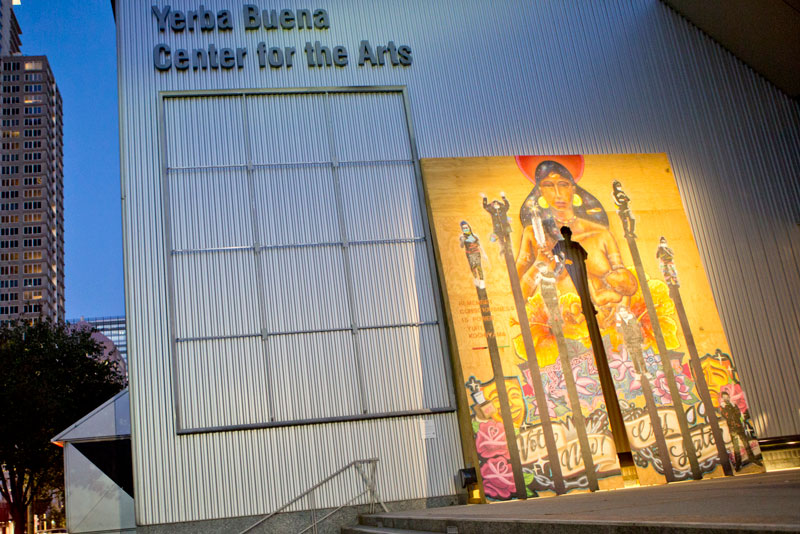

I knew that there were different projects happening around YBCA, even though we’re in COVID and things aren’t as busy as they would be normally. I wanted to introduce the students to the artists that were working on site, and I happened to have collaborated with one of the artists, Caleb Duarte. He’s a friend of mine. YBCA made space for his project to happen, and I wanted the students to, at first, just kind of respond in their own notebooks or drawings to what they’re seeing and what’s happening. But we were actually able to collaborate with Caleb on an installation.

We made these connections between his work and the students, and things just seem to be fitting correctly—right time, right place. We felt that it was, both myself and Caleb, really important to have the young students be involved in this place-making project that deals with memories of monuments and people, to have these attributes of greatness placed in the public sphere so people can acknowledge it. Who better for us to acknowledge but the youth and the next generation of artists, thinkers, makers, and leaders?

We wanted to show the students examples of monuments and different statues that weren’t so western-based, in a sense, with a white male gaze on it. How do we see a monument? How does maybe a single mother see it? How does a child of a single mother see who her hero is? How does a hero look to a child? So, just posing these questions, looking at examples, and then having students experiment with cameras, which by the way, most of them had never used a camera before.

You know, they’re pretty young, and cameras are actually not really popular anymore because you have phones. But they really love using the technology. Give them the camera, and they’re off for an hour just taking pictures. We got them to concentrate on the portraits of themselves and then we went and got them printed. I then asked what the students wanted to do with it. I asked if they wanted to color in their clothing, and they were really into it. So they decorated their clothing and gave it a little more personality. With that done, during the installation, one by one they installed their portraits onto Caleb’s artwork.

RR: That’s so exciting that the students got to see themselves.

FA: Yeah, it’s something. I always wonder how young people take in, accept, or react. Sometimes they’re just like it’s nothing, but then sometimes it’s really cool. Plus you never know if the impact just comes out later. They’re in this other place in their minds, and it’s a wonderful place, but it’s really hard to gauge sometimes. It’s the world of an eight-year-old or a seven-year-old, and I don’t know if they quite grasp different situations.

They don’t know what the stock market crashing means. They don’t know that they’re being put into this really prominent space for people to see them as leaders. So, it’s interesting to see their reactions.

RR: So, you talked a little bit about this, but what do you think the impact is for a student to be able to show up physically and work with you? We had talked about how you were originally planning to do something a little more tech-based, and then through our conversations, decided that the students had so many hours of screen time and we would rather be doing something more tactile. What was it like coming back to choosing to do something in the physical realm? And then, what do you think the impact is for students to be able to show up and work with you in person, as opposed to over a video call?

FA: I think that’s a really great question. I think it’s one that has been looming for the last, I want to say the last five years, definitely last 10 years with the advent of smartphones and people being connected every single moment of their life, and having a machine in their pocket that can take you from one cartoon, to one movie, to one meme, to one chat room all within one minute. So, it’s really hyper thinking that us, as people, are doing.

But as students, they’re young. They’ve grown up with it. Ever since they were a baby, a lot of them, people just gave them a phone to keep them entertained. And I think that their shift into the pandemic COVID period was probably the easiest out of all the different generations because they’re so well adapted to being on screen, at least this is from a person who sees it from the outside. They’re so used to it that it’s habitual, or even an addiction.

So, the issue with students, even with my own kid, is screen time. How much time is too much? Before the pandemic, in classrooms when I’m teaching high school kids, most of the conversation was around, “Okay, put your phones away.” Teachers were thinking about different ways of taking the phones away because the kids wouldn’t leave them alone. Then, all the sudden, we jump into the COVID-19 distance learning, and it’s screen time eight hours a day for work. Then for their leisure time, they can’t go outside. So leisure time is more screen time.

I guess what I’m saying is that I think that it’s really important to come in and have these kinds of tangible experiences, hands-on work, that’s away from a screen. Even with this smaller group of seven students it takes some time to get them away from the screen, even though they’ve been on a screen the whole day since eight or nine o’clock to two o’clock when I arrive. Sometimes that transition takes up to 10 minutes. They don’t want to get off the screen. Even if they’re with the teachers they still want to stay on the screen.

The issue of digital addiction, I think, is something that’s going to be even greater now because it was such a big obstacle in classroom teaching. That was the biggest concern, kids not being present because they’re on their phone. Present physically for sure, but just not being there. They have air pods on, computers going, music’s going. They’re just not present.

I think I’m digressing, but I think that it is good to get away from the screen.

RR: What do you think it’s like for them to be able to work with materials and be in this physical realm with you? What is the impact for them to be able to actually see you in person and play with real life, 3D objects and materials?

FA: I think that what you just said, if I just reversed your sentence, is exactly what’s happening. It’s like we’re playing. So, one day we made paper sculptures. We tried to make robots, making shapes out of paper and using tape. All of a sudden the students are on the floor making robots out of paper, and they’re gone. They’re into it. They’re really just engaged and making, and doing, and playing. They remind me of me when I was a kid, and I had little toys, and I would set up a whole world just playing. I could do that for hours. To tap into that with just paper and tape was, to me, just great. The students that were there were really getting into it.

It was also rewarding to see one student progress a whole lot, as far as being able to participate and be part of the class. I worked with him last year, and last year out of 10 classes of working with him, I think he didn’t participate in a single one. And this year, he started off like that but by the third class, he’s into it. I think he’s having some cathartic experiences. It’s just soothing to him. He’s creating monsters, he’s painting, and he’s participating. He’s listening. He’s just switched, at least in my class and hanging out with me. Every time I go I’m really curious and interested in seeing how to engage him so that this specific student continues to have this outlet, and for it to be a positive thing.

And so, like today, I’m still formulating what we’re going to do in the class. Things shift and change. I can see the other students, the little steps they’re taking in making artwork. Some kids are still kids, they’ll just make all kinds of stuff without any kind of restraints or anything stopping them. And there’s other students who, at the age of eight-years-old, can’t, for whatever reason, make doodles or cartoons, or color and experiment. I don’t really want to get into the reasons why they stop, but I want to have them be able to use these tools, use their hands, to free themselves in a safe space. I think it’s really valuable for them to have this experience, kind of like a guided creative meditation.

The teachers that I’m working with are proving to be really, really caring and attentive to the students. I can see that a bond is growing between them. It’s nice because it’s not a burnt out teacher who’s tired. It’s these young people who are taking care of these younger people, and they’re really into nurturing each student.

I think that one of those silver linings of this experience is that the space is so big and we have so few students. There are seven students at this point, and we have three teachers, plus me. We’re just able to really hone in on specific needs for each student. We can give them attention without worrying about the other 25 students who might go on some other tangent. I think that’s a really special opportunity because the students have the tools to make art, but then they’re also being supported by the teachers.

And the administrators are there too. They’re always around. So, there’s a bunch of adults for a small number of students, which almost never happens.

RR: And you talked a little bit about the students getting to have this as an outlet to self soothe or to explore their mind. I’d love to talk just a little bit about what it is about teaching that you love? Why do you keep coming back to it?

FA: Well, one thing I do enjoy about teaching is it keeps me young in the mind. So, you just get to pick up on a lot of trends and things that are happening that aren’t necessarily aimed at me. So, I think that, with even the younger groups, I just get to know about new technologies, new songs, new jokes. It just keeps me fresh in a sense. I think that their stories also lead to a bigger story. So, it informs the sentiment that different projects that I take on, want to have.

So, in a way, it’s fuel for me. It’s something that I keep in my realm of ideas. What is needed? How can I do something that is functional? That is something that has always been a question of mine. Is art for art’s sake or is there a function for it? How much poetry should there be in a transformative project? If it’s just transformative, just give them the money to buy a computer. You know what I mean? Or should we do a whole opera behind it, and work for it, and then get the computer?

I think that teaching and working with communities puts a grounding towards the dream. So, if we continue to dream it’s fine, but when do we wake? How can we wake in a dreaming moment? I guess in a sense, these children are going to be teenagers, adults, and old people. So working with them becomes more philosophical, like moving through time.

In the past I’ve taught in jails, and that was just too much. I just couldn’t do it. I did it for a few years, and then it was too harsh of an environment. I don’t think right now I’d be actively pursuing stuff like that, but it’s the system. You know? It’s the bare bones of the dragon, and you’re trapped in there. And then when you’re working for it you’re trapped as well.

The school system is kind of like that too though. It’s kind of like this philosopher who compared schools, hospitals, and prisons to each other. I forget his name, but all three are the same exact model. If you look at the buildings, they’re built the same. In elementary school you’re taught to follow a yellow line to go to your class. In jail you follow a yellow line to go into your cell. And so, that’s how systems are built, in the imagination of this punishment regime that comes from…I don’t know. Victorian Age? Or forever? So, that’s another battle that as educators, and artists we’re battling too. How do we teach, how do we correct? All of these things come into my teaching practice. If I’m the one teacher that’s there, and can advocate for my student to not get kicked out, then I’ve done my part. That’s my art. How much poetics do I need behind that? I can see that this person—he just needs to talk with somebody, or something needs to happen. He doesn’t have to get kicked out. He doesn’t have to go to jail.

That’s all part of it because these kids are nine-years-old, but they’re growing up super fast. Teaching them art is a way to make decisions. We learn abstract ways of decision-making.

RR: Yeah, and it’s really beautiful to hear. It comes through so clearly in how you interact with the students and the space that you create so that students have the safety to explore their imagination. It’s a beautiful thing to watch, Fred.

So, we talked about a lot of different areas around the work that you’re doing and the relationship you have with your students. Is there anything that we didn’t get a chance to talk about that you want to make? Anything you want to leave me with?

FA: I guess, my dream project right now is I want to open up a comic book shop here in East Oakland. I’d like to make a comic book shop/gallery where people from East Oakland can come through and read comic books made by people of color with black and brown superheroes. I’m actively trying to write grants right now to make this happen. Successful artists, to me, are making projects, but they’re also following their dreams. They’re kind of making a round robin and hitting every point in their life. I just wanted to put that out there in the whole universe and see if it’ll manifest itself.

RR: Thank you for making the time to have this conversation. It’s always wonderful to hear you talk about your work, and specifically your work with Bessie Carmichael students.