Fri March 13th Open 10 AM–5 PM

A Poem the Length of a Soccer Field

The 2019-2020 YBCA Public Participation Fellow cohort was originally gathered to collaborate and build on communities-based projects that demonstrated the mobilizing of public participation. However, as the Fellows worked on bringing their work to fruition, the world was hit with COVID-19. The cohort were then challenged to grapple with the question: what is public participation now?

“I have a deep philosophy that everyone is an artist, and everyone is a writer. We’re all poets. Everything we write about ourselves is a poem.”

Tavia Stewart has not always considered herself as a writer. Long before co-founding Chapter 510, an Oakland-based youth writing and publishing center, she explored a wide variety of career paths from psychology to music business before choosing a creative writing major out of a USC course catalog on a whim. “Words as an art form—I didn’t understand that was a thing,” Stewart said. “But now I am really interested in the intersection between all the different arts; performing, visual, and the literary arts.”

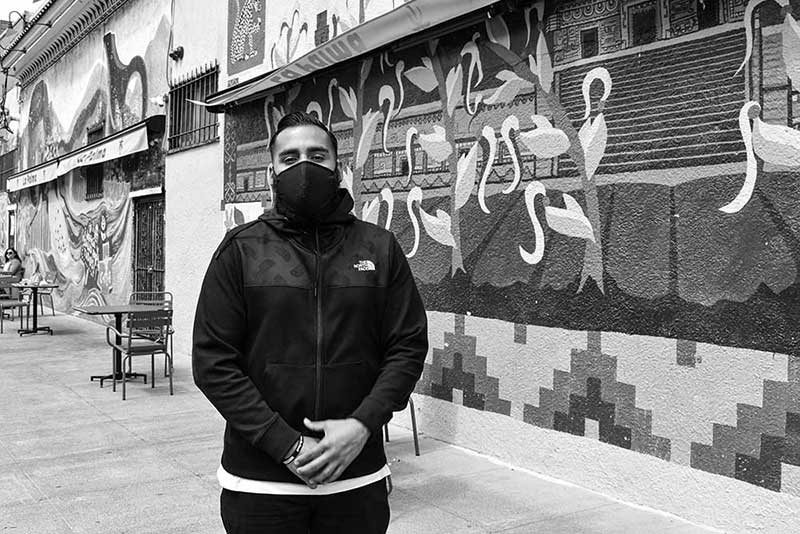

Stewart has a longstanding passion for large-scale collaborative literature projects, from a decade of work at the international online community National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) to creating walking audio tours around Oakland. In 2015, Stewart opened Chapter 510’s brick-and-mortar center with founder Janet Heller on Oakland’s Telegraph Avenue, offering workshops, tutoring, and field trip opportunities, not to mention publishing 20 youth-written books each year.

As part of YBCA’s 2019-20 Fellows cohort, Stewart dove into examining her artistic practice and developing community-based projects that encourage and activate public participation. “The fellowship gave me a space to think about my work in the community in Oakland as a white woman,” she said. “And to think deeper about being a publisher of youth, and mostly youth of color, and explore ownership, publishing, the power of publishing, and who holds that power. It really showed me how important it is that artists are activists. There’s so many ways that artists can engage, and it’s so important that we continue to do so.”

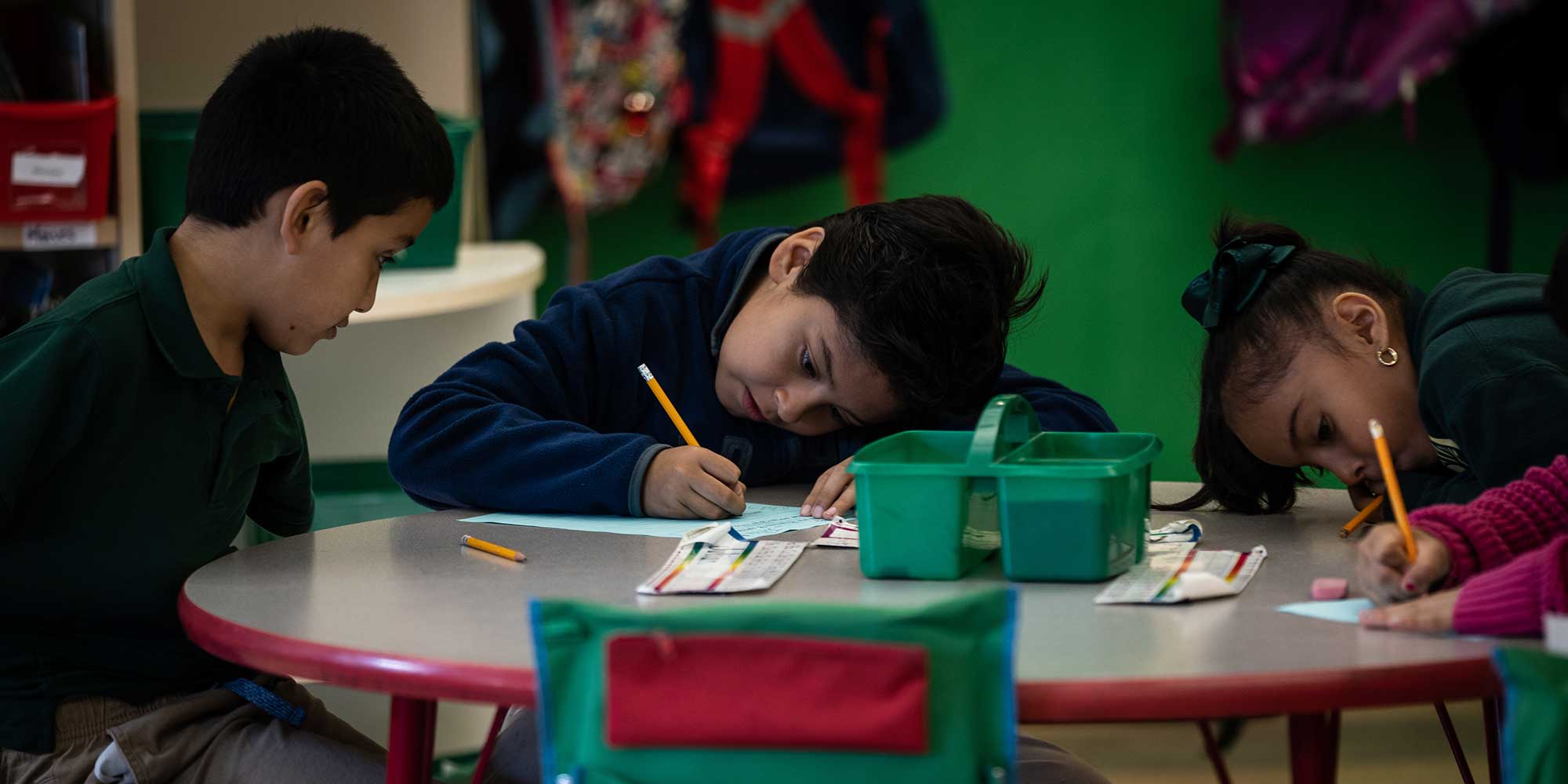

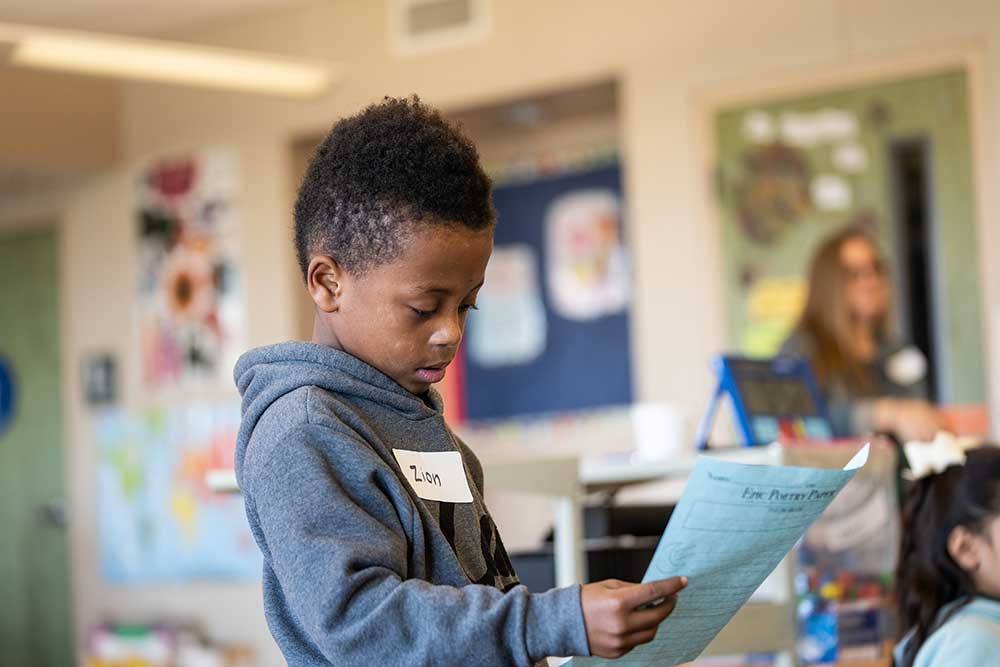

As far as public participation—Stewart had just the big idea for that. For the past three years, Chapter 510 has partnered with Acorn Woodland Elementary to host an Epic Poetry Day. With an updated curriculum each year exploring the elements of an epic poem—setting, character, conflict, in media res, home-to-home cyclical journeys—300 students collaborated to write their own epic poems, drafting one part before sending off their section to the next group and so on. “The poem itself went home-to-home,” Stewart said. “So the poem started in one classroom, touched every other classroom, and then came back around to the first classroom. And the poems are hilarious, because they’re written by kids. You know, ‘And then they got in a Corvette. And then they went to space!’”

For this year’s Epic Poetry Day, Stewart was, of course, thinking bigger. “Each year, we try to simplify the plan. But do we simplify it? Of course we don’t! Because we always have another really good idea.” What if she could expand the scope of Epic Poetry Day beyond the youth-focused mission of Chapter 510 to be an intergenerational project? As a YBCA Fellow, Stewart worked closely with YBCA and fellow cohort member Ericka Scott to imagine a new, expanded format for Epic Poetry Day. With the support of the YBCA Fellowship, Stewart reached out to the newly-formed Oakland Roots Sports Club about distributing a poetry form available in English, Spanish, and Arabic among kids and parents alike at one of the team’s first professional soccer games. After collecting the forms, Stewart planned to compile all of the responses into one long epic poem “the length of the soccer field!”

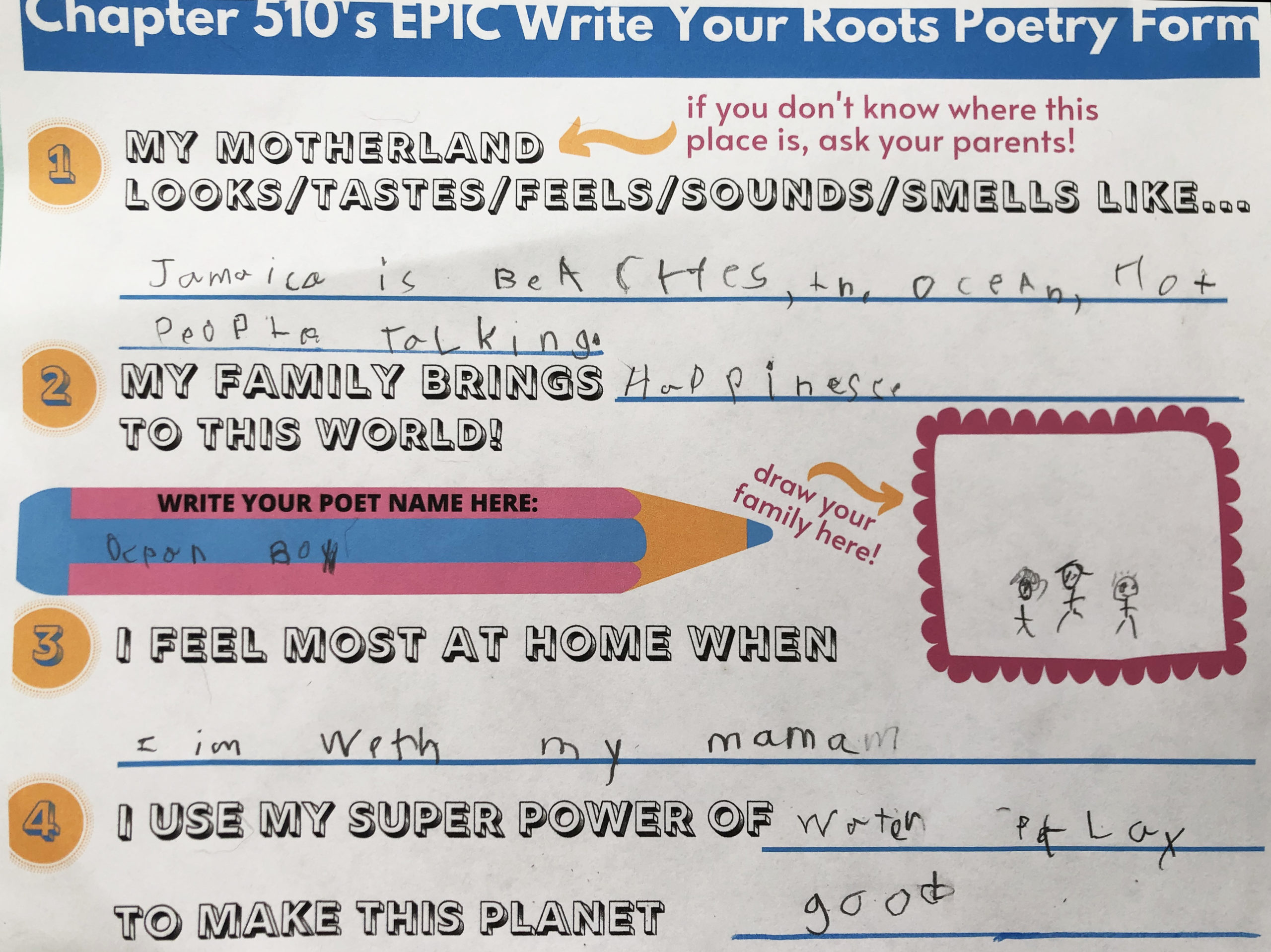

Inspired by a recent 2nd grade curriculum unit designed by Chapter 510 teaching artist Perla Yasmeen Meléndez, Stewart decided to focus the poetry form around the concept of home and motherland, asking: Where did you come from? Where are you now? Where are you going? Stewart and Meléndez created several fill-in-the-blank poetry prompt worksheets for kids and adults to fill out individually and together, posing sensory questions like: What does your motherland look like? What does it smell like? What does it taste like?

Though Stewart was initially concerned about the younger kids’ ability to grasp a nuanced concept like motherland, she was blown away by their responses. “Many of these kids have not ever been to where their parents are from. But for them to be able to translate these ideas into smell and taste and touch and feel was really beautiful. Kids are natural poets.”

My motherland looks like colorful town

And smells like fresh air all around trees

Tastes like pure life

An ancient peaceful place.

“This was written by a 4th grader,” Stewart marveled. “Then the next stanza was written by someone else.”

The feeling when I’m in Guadalajara

Hot weather, the smell of the rain

The city is like heaven

That’s how my motherland is, just beautiful.

Stewart acknowledged the many challenges of public participation, especially with encouraging people to share details about their home and personal history. “What kind of information are we collecting from the public? How does it work? How are they feeling lifted up and included?” she said. “During this time of suspicion of participating in anything, and the era of ICE and the era of Trump, it was a big experiment. But it’s poetry, you know?”

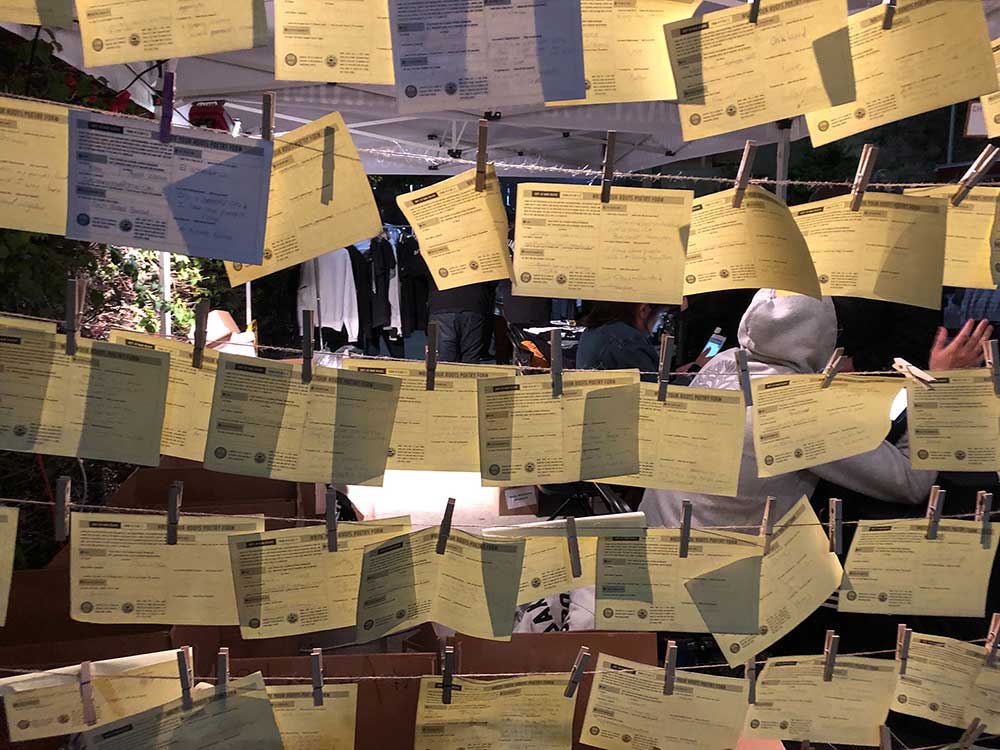

Equipped with 100 completed poetry forms gathered at an Oakland Roots game in October 2019, Stewart decided to see how far the project could go. She spent the rest of the school year handing out the poetry form at Chapter 510’s community events before the COVID-19 pandemic and the Bay Area’s shelter-in-place orders upended all plans in March 2020. “Obviously it’s been really hard for everyone. We shut down the Chapter 510 writing center. We moved all of our everything online. We’re terrified.” Stewart put her plans on hold and brainstormed new ways of adapting the project for a socially distanced world, with the support of the Oakland Roots.

Ultimately, Stewart decided she still wanted to close out the poetry project with a community event. “How do we get the youth of Oakland to participate in this, when we can’t go to them? We’ve discovered as an organization that going to the youth is always the best way to engage youth in writing, because of access,” she said. “So it was a challenge to pivot our programming online and partner with our educators and teachers and principals, and see how many people would participate in this project.”

Stewart shifted the Epic Poetry Day to an online event held on April 27, 2020. Hosted by Chapter 510, the event featured frequent Instagram Live streams, DJ sessions, and poetry prompts shared on social media. Educators at Acorn Woodland Elementary and other local schools encouraged students to fill out the poetry worksheets, available online as Google Forms or as downloadable PDFs designed to look like coloring book pages.

With hundreds of worksheets coming in online, the Chapter 510 team was kept busy updating the website’s live version of the epic poem, adding each newly submitted poetry form to the end of the text. Stewart loved watching the pieces of the epic poem come together in real time. “Imagine that—we’re all stuck at home, but we were all writing poems together,” she said. “It was an amazing way for us to connect.”

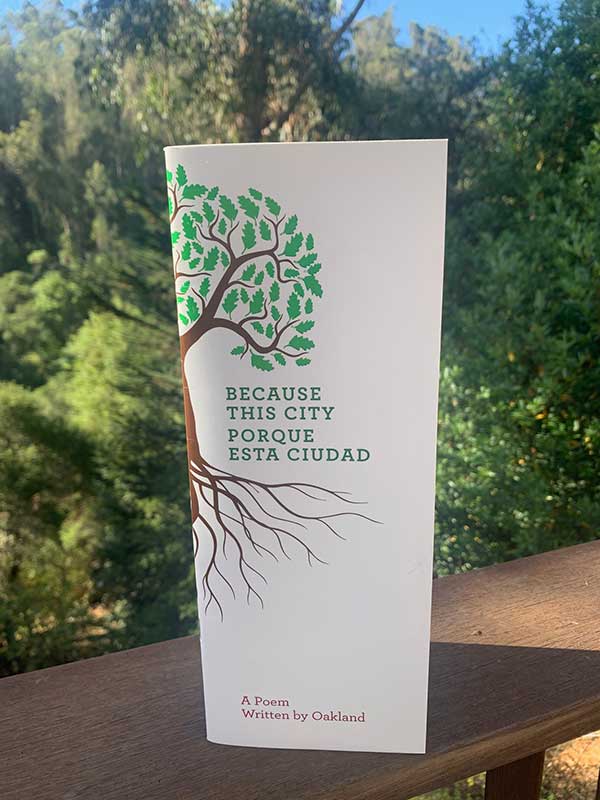

After the event, Stewart and Meléndez compiled all of the submissions into one epic poem spanning 60 pages, then edited it down to 25 pages and added a complete Spanish translation by Meléndez. The final poem, titled Because This City, credits all of the contributors by first name. The complete epic poem, originally planned to be displayed as a seemingly endless scroll in YBCA’s lobby, was published as a downloadable PDF on the Chapter 510 website and several copies were printed as a physical book. Stewart was so impressed with the variety of submissions that Because This City also contains an end sheet compiling all of the unique smells people submitted.

But there were also some ideas that just kept coming up over and over. “So many families wrote about the different states that they are from in Mexico,” said Meléndez. “Everyone had in common that they loved the smell of wet earth in Mexico. Tierra mojada. You ask 500 people, and so many of them identify with this one memory.”

What about things in Oakland? “A lot of people talked about the salty, brisk air, the oak trees, and local landmarks,” said Meléndez. “I loved that people included Oakland slang. You know, everyone calls Oakland ‘the town.’” Translating the mostly English regional slang into Spanish proved to be a fun challenge for Meléndez: “How can I make these words sound both colloquial and place-specific?”

Stewart and Meléndez also created video readings of the poem, in English and Spanish respectively. Though a little uncomfortable reading other people’s personal revelations on camera, Stewart was thrilled to share the epic poem in a new way. “If I was Oakland and I was writing a poem, this is what it would sound like,” said Stewart. “It really kind of personifies the town in a beautiful way.”

Stewart looks forward to engaging public participation by sharing the poem with the Oakland community, both in public installations around the town and in person, when people can gather together again. “Next year when we can have soccer games, we’re going to print the poem as long as a soccer field, and roll it out on the Oakland Roots pitch.”

Stewart hopes the youth participants feel empowered as poets and as part of the Oakland community. “Any time you publish a young person in print, something magical happens,” she said. “The book’s been translated and it’s real and it’s out there and it’s public. Just that feeling of, ‘My words are worth this beautiful book.’”