Mon April 28th Closed

Exposing and Empowering Personal Agency

This article is part of the ongoing Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? experience. This collaboration with Art+Action is part of their COME TO YOUR CENSUS campaign—powered by San Francisco’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA)—which hopes to mobilize the public to take the 2020 U.S. Census. We want everyone to be counted and receive their fair share of funding and political representation for their community.

If you have not already done so, we highly encourage you to take the 2020 US Census.

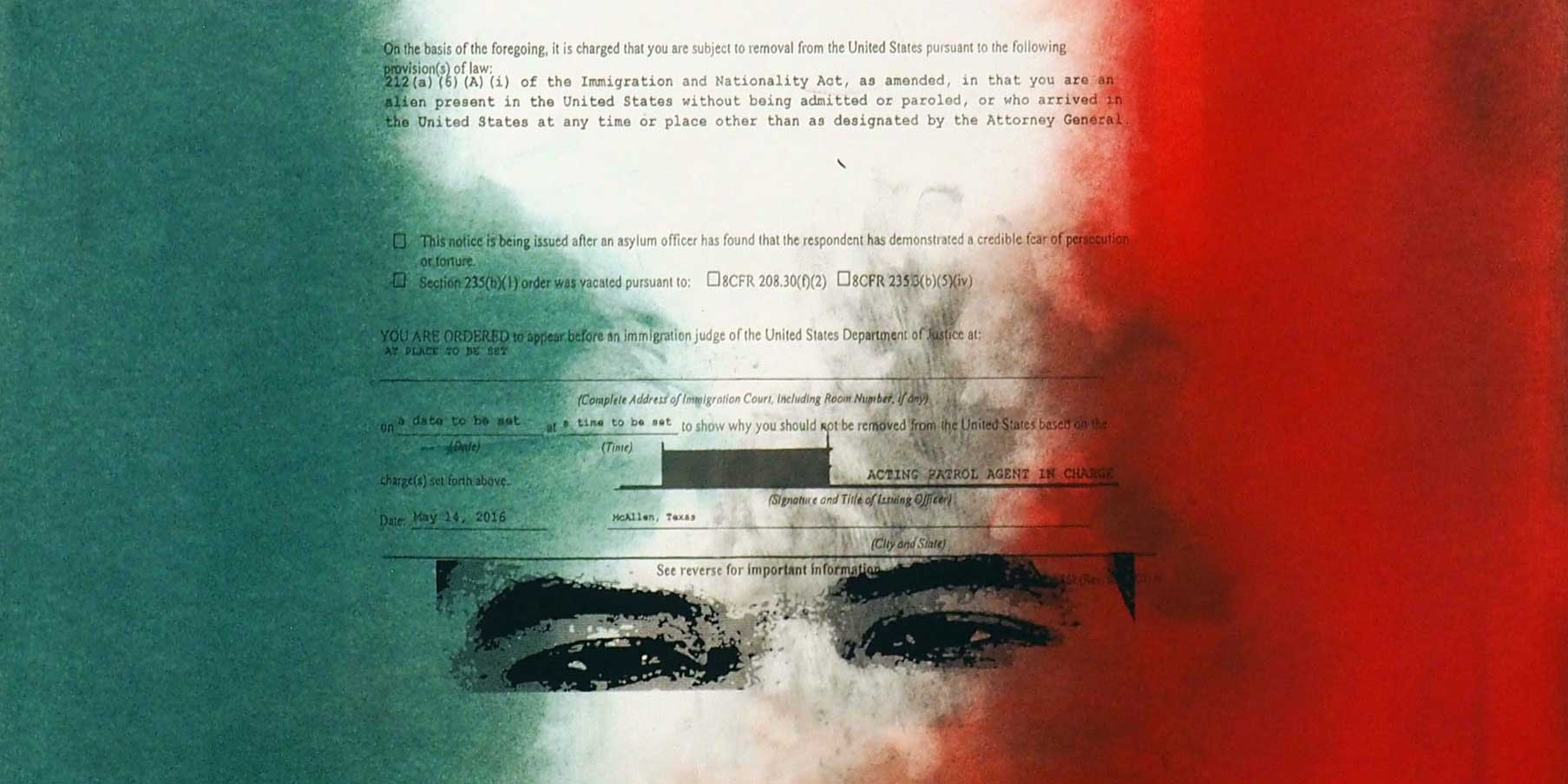

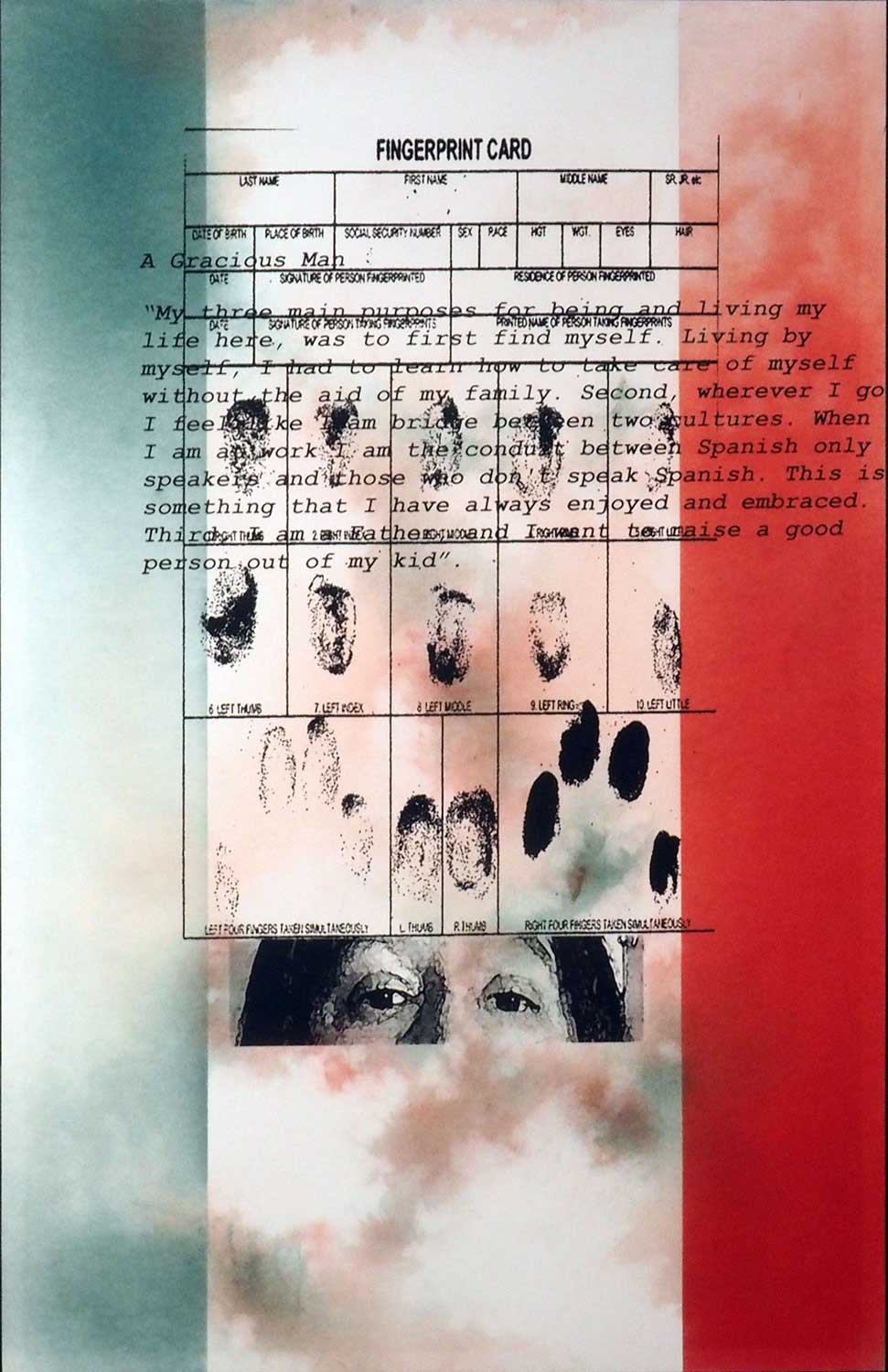

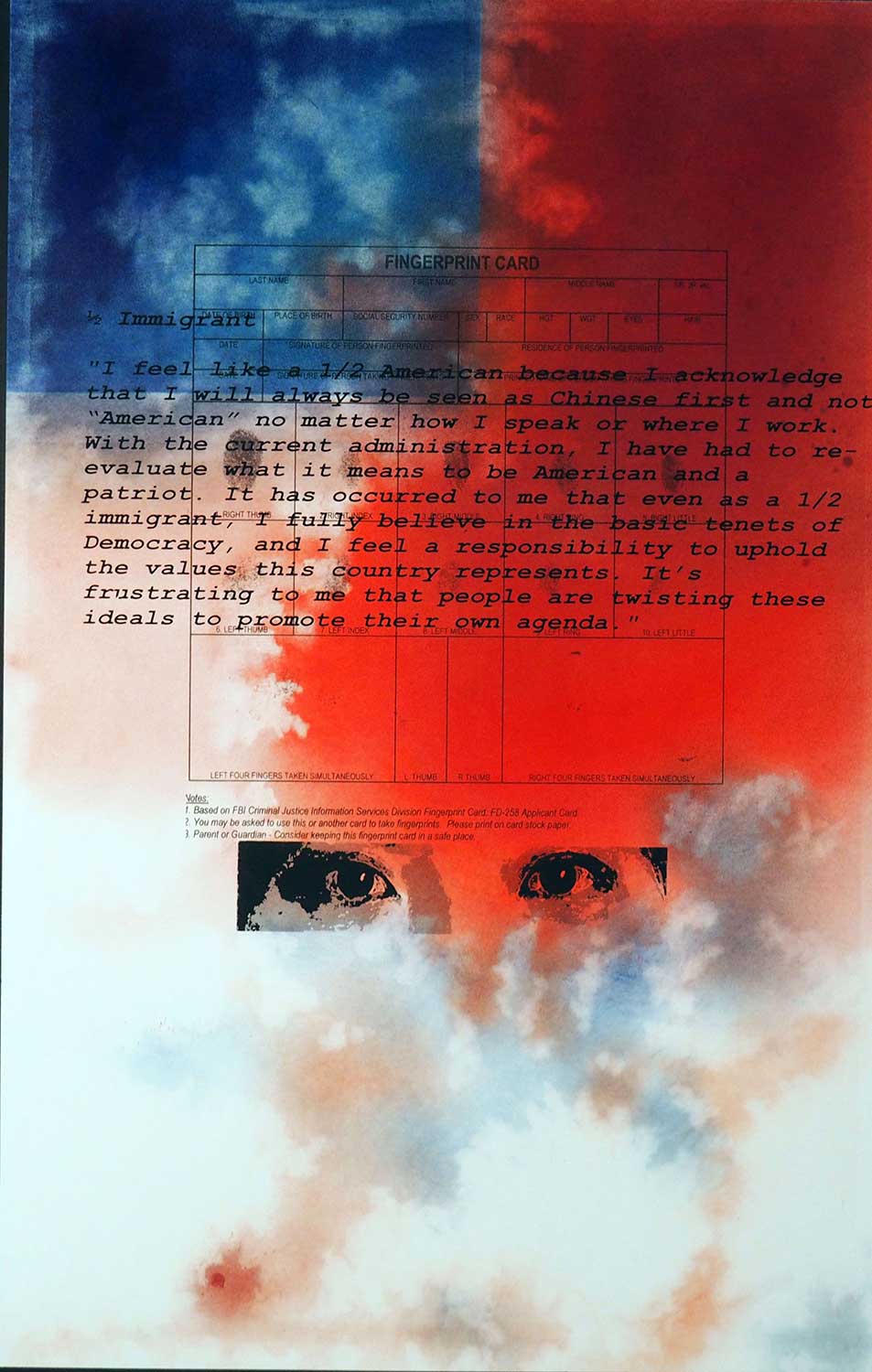

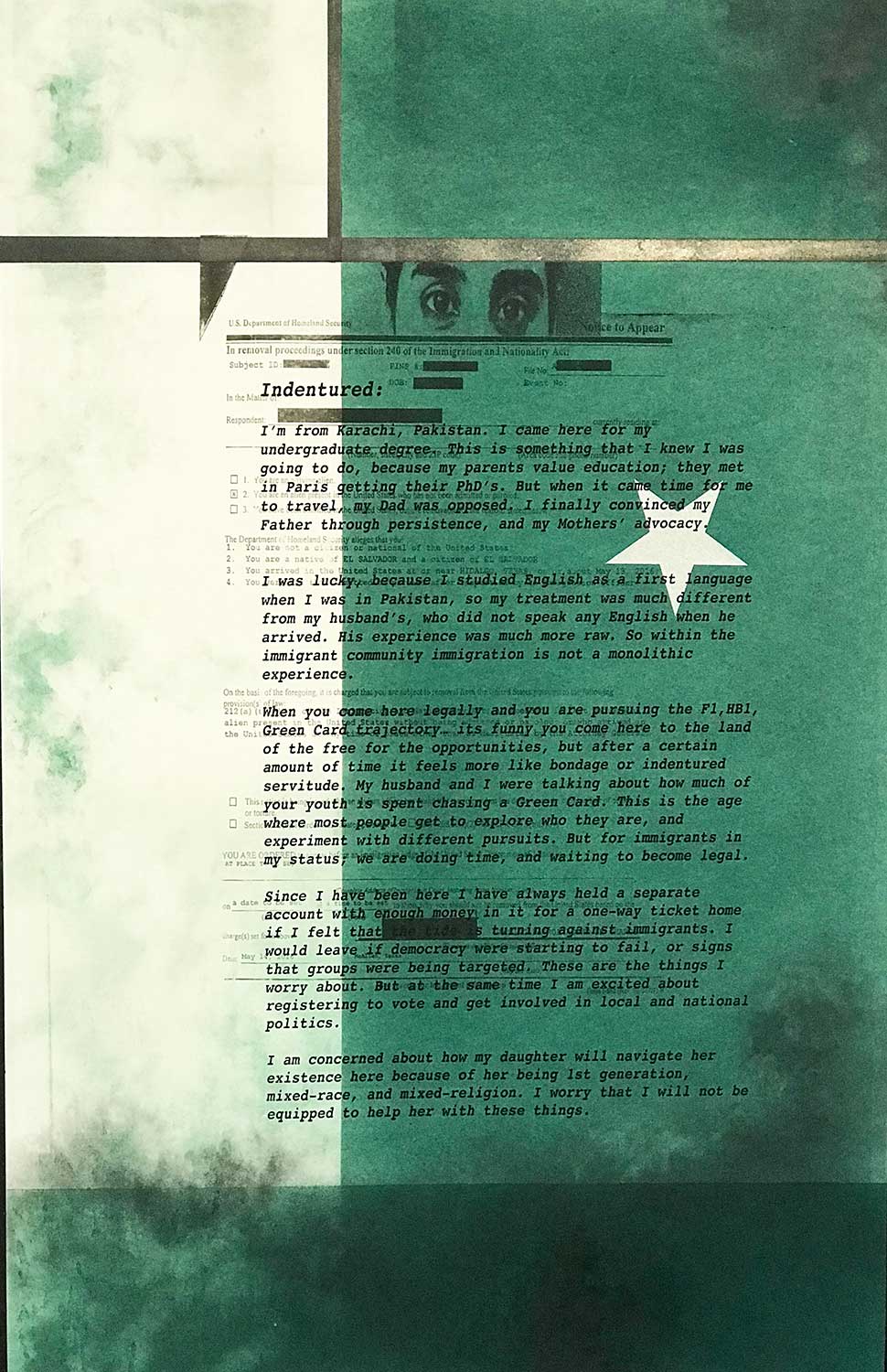

Rodney Ewing is a visual artist based in San Francisco. Ewing’s drawings, installations, and mixed media works focus on his need to intersect body and place, memory and fact to re-examine human histories, cultural conditions, and events. For Come to Your Census: Who Counts in America? YBCA and Art + Action commissioned Ewing to create the participatory work Who are you? / How do you want to be counted? This work evokes the ten-card, a tool used to record fingerprints that allows certain agencies to check an individual’s name, age, race, physical statistics, and criminal activity.

Ewing sat down with YBCA Curatorial Project Manager Fiona Ball on April 27, 2020 to discuss his ongoing artistic exploration around systems of identity and how his work shines light onto his audience’s personal agency.

Fiona Ball: Hi Rodney, thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me. Let’s start from the beginning. How did you first get into your artistic practice?

Rodney Ewing: I thought I was going to be a graphic designer when I graduated from high school. I was fortunate to attend a high school that had a really good art program. The first thing that came to my mind when thinking about a career was I have to make money, I have to be able to support myself. I thought graphic design was going to be the way to go. As I matriculated through college I started taking other courses. When I took a printmaking class, that was it for me. I switched to fine arts and decided I’d figure out what to do for my career later.

I was pretty much a full time printmaker through my BFA and MFA program. But after I got out of school, it seems all my experience printmaking still supported my drawing practice. As I began getting back into my drawing practice that sort of led me into exploring other mediums as well.

FB: Then when did you start thinking about the tencard and different systems of identity?

RE: I started thinking about the ten-card maybe 11 or 12 years ago. While teaching through Southern Exposure, I used the ten-card for an art project. It initially started with looking for different ways to engage the viewer. I realized engagement doesn’t always come from a print, a drawing, or an installation. I wanted to figure out what I could do to really subvert the idea of identity from the participant’s point of view where I’m engaging and empowering them. I’ve been fingerprinted a lot because of being a teacher and being in the military, but that form falls short. It doesn’t do anything for the participant. It doesn’t say things like that you call your mother every day, you check up on your neighbors, or things like that. Things that are important. So I added an extra section to the ten-card for people to what they think is pertinent to their identity. It was a way of taking that institutional method of identification and handing it to the public.

FB: You’ve been thinking about this idea before the curatorial team approached you to participate in Come To Your Census, so how do you see this project relating to the Census and the themes we’re looking at in the exhibition?

RE: The Census is really important–it’s something that we have to participate in. The information that it gathers informs the federal government, schools, demographics, and hopefully what people need. Ideally that information is used to direct resources to the key places. But I feel that institutional forms always fall short. They don’t give you any opportunities to talk about yourself other than within the structure they give you. When this exhibition came up, I decided it was an opportunity to expand on this idea. Especially with YBCA’s large audience and the traffic coming through there, the piece would really get a broader sense of what people think about themselves–how they interact with the community, how they identify, and give them an opportunity to be able to freely write and document themselves and in a way that feels genuine to them.

FB: When we were originally talking about the artwork, we talked about you holding office hours to engage with visitors in-person. Why do you feel this is an important aspect of the piece?

RE: It’s really an intimate thing to ask somebody to record their fingerprints. If we just leave the ten-cards out some people will do it, but I know I would be suspect if somebody just came up to me asking for my fingerprints. I would want to know what are you going to do with them, where are they going, and why are you doing this? So I wanted to have a person there that visitors could have a conversation with and interact with.

FB: The project is meant to be cumulative in that we’ll have all the completed ten-cards hanging in the space. What do you think that would hopefully do for people seeing other’s responses as they’re filling out their own?

RE: My hope was people would get inspired. They would start seeing what other people read and maybe they will find some connections. Maybe they would find themselves in different people’s writings or drawings or however the individual chose to represent themselves. Hopefully a certain amount of freedom and accessibility to somebody else’s art practice will come through their participation in the installation. You know, once people fill our the cards, the artwork is not mine anymore. I always find that a really beautiful thing, when you can make something that’s a little bit larger than yourself. I actually organize my way out of a job.

FB: So much of your work is about empowering the audience and giving them opportunities to recognize their own agency. I do want to talk about another project that you did with the San Francisco Arts Commission for their Market Street program. Can you tell us a little bit about Human Being: Sanctuary City?

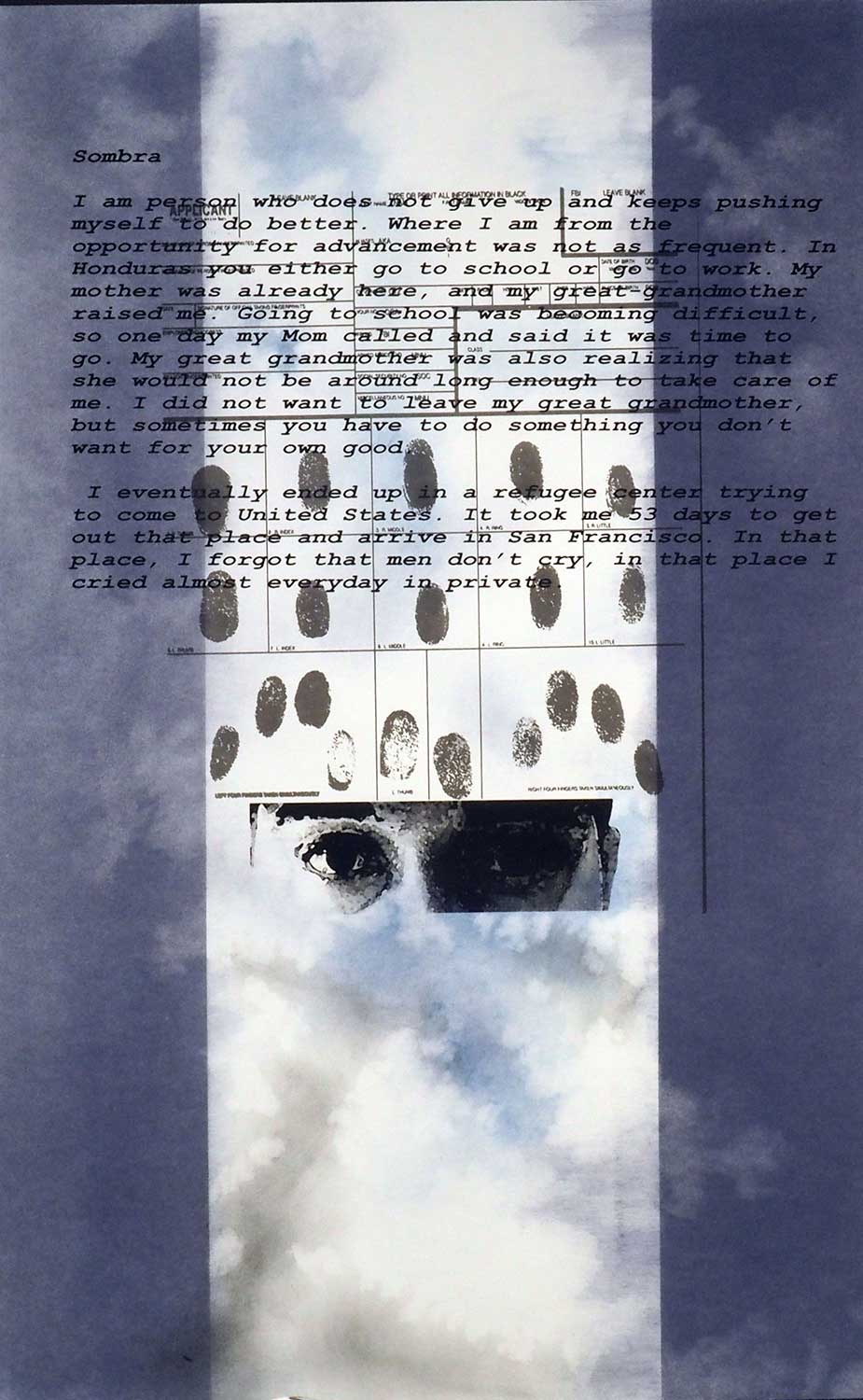

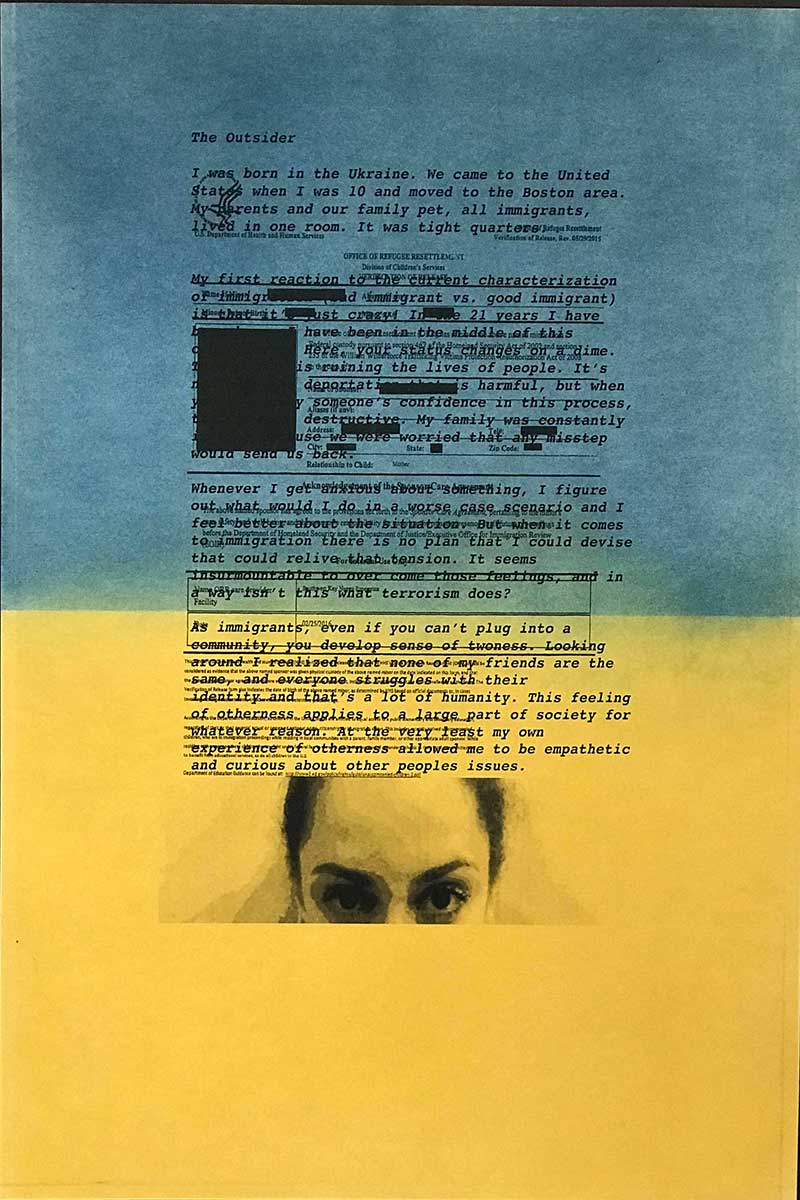

RE: Strangely enough the ten-card project inspired the writing for the SFAC proposal. I wrote that I would focus on six individuals with different immigration statuses. I wanted to have them talk about how they felt about the topic, especially since certain individuals come into power and how it’s becoming this single story about immigration. We all know it’s not the case, but his base constantly buys into this immigration propaganda. Things like “good Americans losing their jobs” but the stories of immigrants are a lot more complex than that.

I wanted to put your human elements into the immigration narrative again, which had slowly been stamped out for the last three and a half years. That project was also a stressor for me because I’m usually pretty insular. I have a subject, I figure out how I want to present that subject, and then I present it to an audience. With this series, I was actually relying on other people’s stories and they were trusting me to do their stories justice.

Then as the project evolved and the Commission wanted different things from that project. I ended up photographing the subject and only using parts of their faces. I just used their eyes, and some of these individuals let me use their fingerprints. There’s other people doing this work obviously, who are standing up for immigration rights and immigrant rights. But art is where I operate and I just want to contribute in my way.

FB: That series is so much about visibility in the public space. It seems very pertinent to relate this to the times we’re in right now because forms of the visibility are changing so heavily. How do you think we can still feel we’re visible in a time where we are so isolated from one another?

RE: For me it’s just reaching out and talking to one another. There’s so many platforms out there. Even if it’s just supporting something someone said on Facebook or talking to somebody on Zoom. Or even if you’re outside and you’re a social distancing but talking to a neighbor around some issue. This is not the time to go silent. I think especially in a time like this is when we really need to start looking after all sections of humanity that exist around us.

FB: I think that’s such a good point and that we have to keep conversations going in some form–we have to keep talking. Right now how are you taking care of yourself and of your community?

RE: I have to admit I went low for maybe about a week. I had to travel down South and help out my mother. She’s older and I had to move her into a different place. I got back to San Francisco just as the reaction to the pandemic was starting. I slid underneath that incident, quarantining, and I think I was just exhausted. I needed to do a lot of things physically for her and emotionally. For example, I couldn’t go into the nursing home with her because they weren’t letting any people around, which I respected. But looking at her through the window I was thinking, I got to go now, I can’t stay.

Then slowly I came out of it and I had to switch gears and started teaching online. I had to be present for my students and then eventually to start taking care of myself. I just started making art. I’ve had this challenge for myself, I make a new piece every day and a half.

I’m lucky that my studio is perpendicular to where I live so I only have to travel about 300 feet. I started giving myself a commute every morning. I don’t do any work in my house. I don’t do any schoolwork or art work in my house. I bring it all to the studio.

FB: What are you working on right now? What are the pieces you’re making every day and a half?

RE: I have a large assortment of silk screens that I’ve used for other projects probably over the last 10-12 years. I just started going through them and making combinations and connections that maybe I wouldn’t have intended before. When I was at Recology, somebody gave me two notebooks of these insurance ledgers. I’m taking the paper out and using that for my paper. There’s something about the way this ledger paper has aged that really attracts me to it.

I’ve also been working with Tahiti Pehrson for a residency with The Space Program. He sent me some of his paper cuts about two weeks ago and this weekend I finally got to start screen printing on top of them. We’re really happy with those, so hopefully he’s going to send me more and we’ll see where it goes. I’ll send those over to The Space Program and we’ll figure out how we’re going to display them. It’s just been keeping me making stuff. I’ve had some people ask me “how can I get that piece you just made?” but I want to keep them all together. I don’t know when the show is going to be, but there’s going to be one. I don’t know who’s going to be with, but it’s going to be shown somehow. I’m just going to make the work and I’ll figure out the logistics later.

FB: Do you see these works as responding to the current situation or is it just your escapism? Is it your getaway?

RE: It’s definitely my getaway. I don’t think any of these pieces on their own respond to this current situation.

FB: I think we need to balance. One of the reasons we’ve asked folks how are they taking care of themselves is because I think it’s so important to admit when we’re tired and when we need to take a break. We’re in such a world of hyper-productivity and we carry this guilt when we don’t meet that. The more that we put it out there that we are allowed to slow down, hopefully the more people can talk about it in a healthy way. Is there anything else you want to share with the YBCA community about the project?

RE: I just want to say how grateful I am. YBCA has consistently found ways since this pandemic has hit to keep me involved. I know it’s not easy. You guys have tried many different methods to make my practice and the project digital. I’m just grateful that you guys keep reaching out and we keep doing things.

Lead image: Rodney Ewing, Home for the Brave, 2018. Dry pigment and silkscreen on paper. Courtesy the artist.