Tue February 24th Closed

Samora Pinderhughes: The Healing Project

I’ve been working on The Healing Project for eight years now. It’s my try at speaking directly to the many damages caused by our society’s systems of prison, detention, and structural violence, and the many beautiful, different, and deep ways that people figure out how to heal themselves and others from the things they go through, in spite of it all. It’s a testament to resiliency, imagination, honesty, and complexity.

This is a spiritual project. It’s about the deep levels we must access to get through the things that hurt us in life; about how much our current and historical US systems (particularly the prison industrial complex) rob us of all the true ways to take care of ourselves and each other; and about how the folks who truly have all the answers we seek are the very people who are never given the power in our society. It’s about abolition and revolution; it’s about death, grief, loss, and process; it’s about anger, hurt, and sadness; it’s about love, relationships, and friendship; it’s about identity, and power; it’s about honesty, accountability, understanding, and forgiveness; it’s about messiness; and it’s about purposefully upending all the current systems to create new ones.

The constellation of pieces that you see, hear, and feel are the result of hard, careful, and passionate work by more than one hundred people around the country who courageously and beautifully shared their stories with me, and over fifty different artistic contributors who helped me bring those stories and ideas to life.

A key question I asked in every single early interview was: If you could design a space with everything you need for your continuous healing processes, what would it look like, what would it sound like, and what would it contain?

My hope is that, as you listen to these voices, observe these pieces, and experience this art, you will take notes on the truths that folks are telling and the ideas they generously share about how to build spaces and processes for healing. The answers, the solutions, that we claim to be searching for are right here. They are known and understood and practiced every day by folks who have figured these things out by necessity, from everything they’re dealing with. But that’s never where we as a society go to find truths. We worship politicians, we adore celebrities, we listen to policymakers, but we don’t listen to the youth, the incarcerated, the folks who have actually been through all the stuff we claim to want to solve.

This project approaches many interlocking issues and realities at the same time, because I believe very strongly that it’s all tied together! We can’t solve one thing without addressing how structural violences are interconnected. Policing is connected to incarceration, is connected to detention, is connected to surveillance, is connected to gentrification, is connected to capitalism, is connected to violence, is connected to loss, is connected to grief, is connected to hurt. And the same goes for solutions—they must be wide-ranging and link many things together if they are to have truly lasting effects.

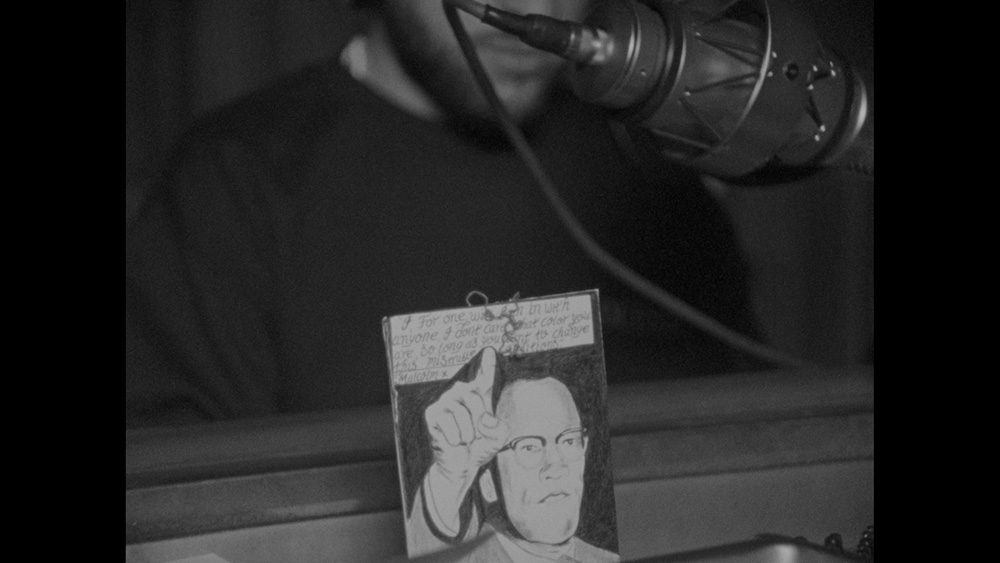

I think what folks are dealing with on a daily basis, and how our society doesn’t honor and admit this or make space for it, can only be reflected through direct testimony and art. Seeing how the entire history of popular US media is built around stereotyping Black and brown and poor people, and criminalizing and dehumanizing them, this project is built as an offering, a counternarrative. In so doing, I’m not trying to heroize anybody. I’m trying to show that everyone is complex and human and multidimensional—that every single one of us has every type of emotion and character inside of us! I want to destroy the binary of good and bad. This is not a project about innocence. It is about messiness, about mistakes, about process, about being a full person, and about reckoning with what has happened to you and what you have done and where all of it comes from.

This project is built to tear down the stereotypes about incarcerated people—the lies that say they’re not brilliant and creative, that they’re isolated from the world of ideas, that they’re not kind and gentle and loving, that they’re unfeeling. It also shows how people change over time and how we have to make room for those changes, and for understanding where folks are at. Some people in our society are allowed to do that, while others are punished for the decisions they make before they’ve been allowed to change and grow and bloom.

The Healing Project is also fundamentally an abolitionist project. I believe deeply in the abolition of the entire prison industrial complex and of racial capitalism, and I believe deeply in revolution over reform. Through these pieces I seek to condemn the policies, practices, and structures (both physical and ideological) of this nation. I hope this project can contribute to the ongoing struggle toward an abolitionist future. I thank Mariame Kaba, Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Cedric Robinson for their daily inspiration and teachings in these areas.

The Healing Project has changed my life in forever ways; it changed how I live daily, and how I think about and practice healing. It gave me a whole community and family—deep and lifelong friendships and networks of mutual support between myself and many of the interviewees and collaborators. Folks like Cyril Walrond and Keith LaMar and Roosevelt Arrington and Peter Mukuria and Ginale Garcia are among the most genius and courageous and loving people I’ve ever met, and I’m so grateful to have their stories. And even though this project didn’t start out as about me, it became my own portal to talk about grief; about loss; about healing and process; about depression and anxiety; about the things I deal with daily never had room for or couldn’t talk about without embarrassment.

The Healing Project started for me in 2014 thanks to my artistic mentor, Anna Deavere Smith. That year, Anna asked me to create a small piece for her institute; I had been studying her incredible process and had been completely transformed by her work, from the questions she asked during interviews, to the ways she listened, to the plays she created, to how she inhabited other people’s words, details, gestures, and essences. So I decided to approach Anna’s interview process from a sound-based perspective as a musician, learning from the ways she had taught me to listen and adding in my personal compositional and then multidisciplinary practice.

My choice of subject matter was originally inspired by my parents, Raquel and Howard Pinderhughes. My growing-up years in the Bay Area were intertwined with their work—seeing it, being inspired by it, and aspiring to be like them. They’re both educators, community workers, and social and racial justice activists. My mom created the Roots of Success Environmental Literacy and Job Training Program, which takes place in prisons and job training programs across the country, allowing people to come together and talk about the root causes of environmental and social injustices. The program is taught by incarcerated people themselves, giving them agency in it. My dad does research, policy, and community work on violence prevention with a focus on trauma, and has developed influential frameworks about the impacts of structural violence on communities and the need for communities to heal from community trauma. He’s also a member of the Brotherhood of Elders Network, which I’ve been so inspired by.

Since that first small experiment with Anna’s institute in 2014, where I interviewed ten folks in Oakland, Richmond, and San Francisco and put together my first concepts, I’ve been working on building as large and impactful a project as I can. This is by far the biggest and most ambitious thing I’ve ever done. I recorded audio interviews with over one hundred people over five years in fifteen different states around the country. These conversations happened over hours, days, and years both in person and over the phone (for those who are still in prison). Many of these folks became my closest friends and family throughout the process. Then I took years to edit, putting folks into conversation with one another around shared themes and ideas. Then finally, I collaborated with many, many genius artists to create original works of music, film, photography, and sculpture that flesh out an entire world of feelings and experiences and ideas surrounding the realities expressed in the interviews. Each piece has a specific purpose and a specific need.

One important note: it’s very intentional that I recorded interviews as sound only. For the sound room, I wanted to take away the immediate assumptions that come with seeing a person’s face, given the decades of context we bring to the visual medium. I wanted to force us all to listen to folks more closely and hear the musicality of their voices—their tones, their rhythms, the spaces and pauses between their words, the ways their voices change as they reflect and speak. The films and physical art pieces are then opportunities to sink even more deeply into the worlds and feelings.

I want to especially thank the three producers of this project, who from the beginning were my absolute guiding lights and are among my greatest inspirations from the history of art-making: Anna Deavere Smith, Vijay Iyer, and Glenn Ligon.

I also want to thank YBCA, who has been a true dream partner for this project and trusted me every step of the way.

Most importantly, I thank the village of people who contributed to The Healing Project. This is a community project. Between all the folks who told their stories and worked on the pieces, more than 150 total collaborators gave of themselves. It is one thousand percent as much their project as it is mine.

Lastly, I want to dedicate this exhibition to several folks who have passed on since I started The Healing Project , and whom I especially hope to honor through it:

Lawrence Dahu Harris

Sharen Hewitt

bell hooks

Nipsey Hussle

Daisy Newman

Greg Tate

With love,

Samora