Tue July 8th Closed

On Empathy

As someone who has spent 20 years working to bring art and creativity to the center of public life, I have long believed that art cultivates the sense of connection, interdependence, and empathy that’s needed to create change. Only by inspiring people to see things in a different or new way, can we find breakthrough solutions to our biggest challenges.

“. . . we must prioritize work that connects us and inspires empathy — our unique ability as human beings to see and care about one another.”

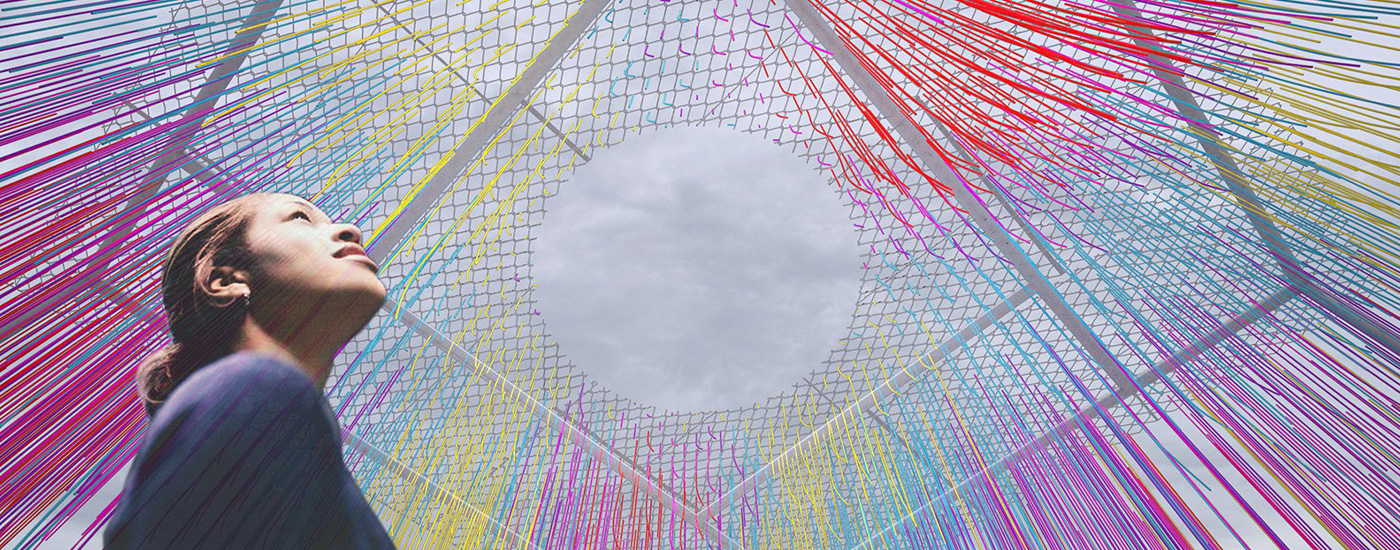

Today marks the opening of the second Market Street Prototyping Festival (MSPF). Born from an unprecedented partnership between YBCA and the San Francisco Planning Department, MSPF engages our citizens to transform Market Street into a destination that can bring together diverse people, neighborhoods and communities. This work is hard. Its about bringing together creative citizens, artists, makers, designers, policymakers, and bureaucrats. Its about everyone’s ability to believe, to let go of our limits and our territories, in order to create a more hopeful and equitable future for our city.

I recently had a startling experience in an underpass just beneath Market Street that only heightens my sense of urgency that we must prioritize work that connects us and inspires empathy — our unique ability as human beings to see and care about one another.

I was walking through the underground passage beneath Fifth and Market at the Powell Street BART Station. It is an awkward, stifling place. A place that rotates ads for fancy phones, purses and jeans but offers no place to sit, no comfort, no opportunity for connection. It doesn’t smell good. It feels sticky. It feels like another one of so many missed opportunities — a public space that could be vibrant and instead simply exists to move people to and from; a public space that discourages inspiration, discourages our togetherness.

Yet, as is almost always the case, there are at least a dozen homeless people lining the walls. They are women and men, young and old, they are resting. Some sleeping and some daydreaming, some tidying and some eating. One, he is here often, is carefully cutting his nails.

A group of young guys with skateboards catch my eye. One of them is on a knee shooting photographs with a smart phone. The others are forming a kind of queue with their skateboards under their arms. It takes me a minute to grasp that the one on his knee is capturing images of his friends jumping the people who are taking respite here. These guys start at one end of the underpass and with a kind of running start, they fly to the other side — jumping at least six human beings along the way, touching their skateboards down in between people like they are speed bumps.

While many of these people appear to be sleeping, or hiding beneath blankets and jackets, one man is sitting straight up and staring straight ahead. He looks exhausted, not tired, but exhausted. A guy on a skateboard jumps over his body. The one with the camera says “let’s do it one more time.” The man doesn’t move. He doesn’t blink.

“Do we care about homeless people? Or, do we simply care about how homelessness looks and feels to those of us who are comfortably or even just basically housed?”

Astonished, I suppose, I quickly make up a narrative that this must be a movie shoot, it has to be some kind of creative project. Behind this incongruous scene, there is a passionate filmmaker utilizing ubiquitous technology to weave a story about empathy — about what will happen to us if we do not see one another as human beings. Armed with this version of this moment, I keep walking to my train.

Once onboard, I realize the skaters have landed on the same train, in the same car. They are boisterous and on their way. I can’t help turning to one who is right next to me. I ask him if he was one of the guys skateboarding in the underpass. He casually affirms.

I press on, asking him what they were doing. His response is a befuddled — like why are you asking — “having fun.” We have a quick exchange that confirms that this was not a creative project, that these people were not consulted as to whether or not their bodies would serve as jumps in an obstacle course. When I implore that these are people, he retorts that they are homeless and that they are sleeping in public, as if the condition of homelessness makes them not people but something else. At some point, he realizes that I am troubled and asks, incredulously, if he and his friends offended me. Of course they did.

At this point, he goes quiet and I thank him for engaging with me. We go back to our corners on this crowded train. All of the skaters get off before my stop. All but one. All but the one I talked to. He stands behind me persistently. Gets off at my stop. Follows closely behind me up the escalator. At the top, he touches my shoulder. He says “I’m really sorry we offended you.” His eyes are wide, heartfelt. He is clearly grappling with something.

But is it possible that he is sorry he offended me? and he is not — at least yet — thinking differently about jumping over unwitting people on skateboards? I mean, I am not seeking respite in a dirty underground space, I am wearing nice shoes and walking toward my beautiful home and family. Is it possible that he sees me, but he still can’t see homeless people seeking respite in a BART station?

“… we have to turn it into a passionate effort driven by art, inspiration, creativity, and compassion to help us understand what might happen if we do not see each other as human beings.”

I often hear people say that the number one issue for voters in San Francisco is homelessness, but I wonder — do we care about homeless people? Or, do we simply care about how homelessness looks and feels to those of us who are comfortably or even just basically housed? This is one of the many reasons why YBCA is playing a leading role in an important ballot measure this year — Prop S which is a historic coalition working to save the arts and end family homelessness. We can’t solve the problems that we face in this world if we do not see one another regardless of our differences. It isn’t just “homelessness” we need to care about, we must also address the lack of empathy we have for people whose lives are different than ours.

I desperately want to go back to the scene in BART. We have to go back there — and to all the unfortunate scenes like it across this beautiful but broken country — we have to turn it into a passionate effort driven by art, inspiration, creativity, and compassion to help us understand what might happen if we do not see each other as human beings.