Thu July 3rd Open 11 AM–5 PM

طراوت | TARAVAT

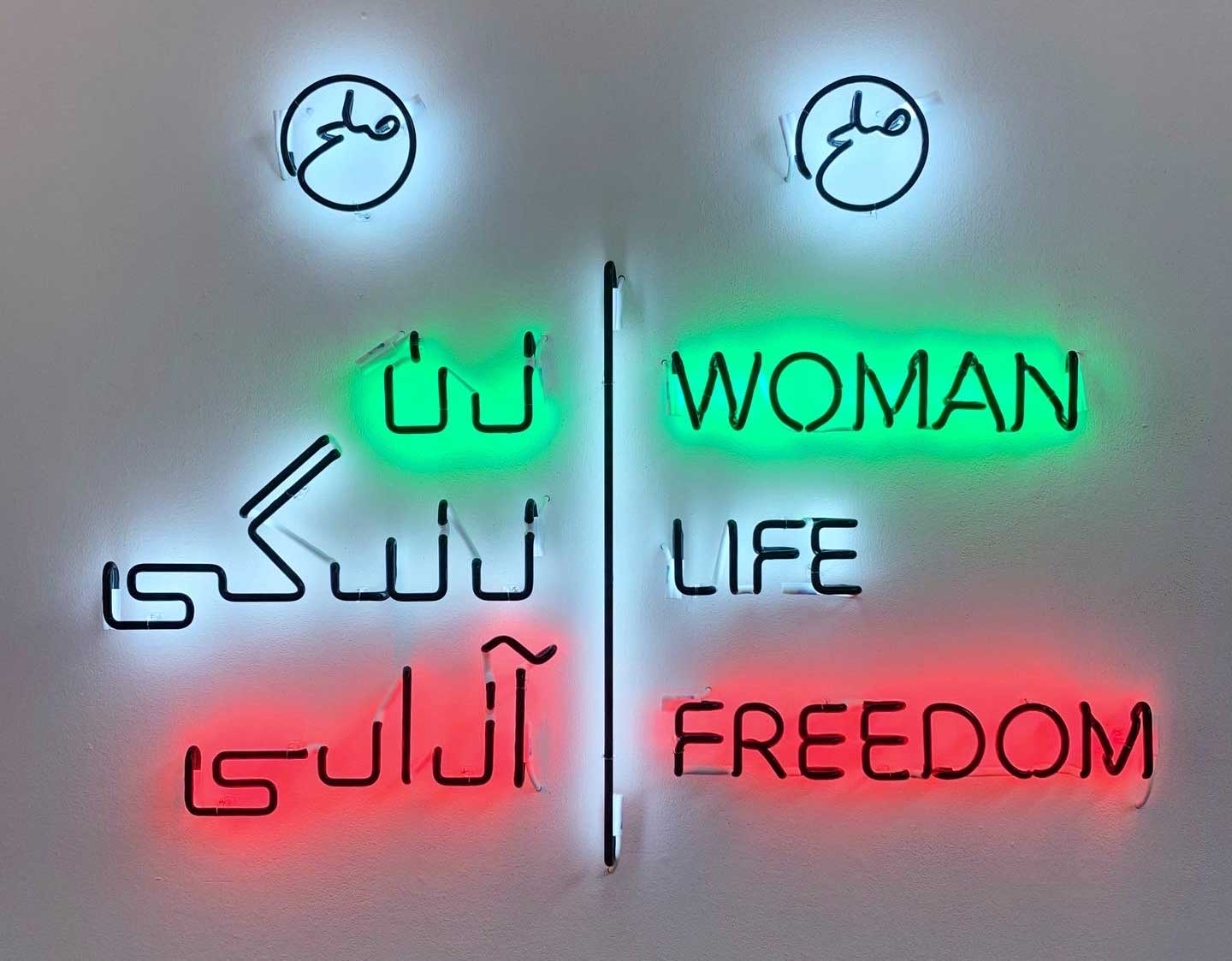

Taravat Talepasand, Woman, Life, Freedom, 2022, Neon.

This essay was originally written on December 20, 2022 and is featured in the exhibition catalogue for طراوت | TARAVAT.

Sometime in mid-October 2022—just five weeks into the nationwide protests that continue to unfold in Iran in response to the killing of Jîna Amini—a mural-sized propaganda poster appeared in Valiasr Square in downtown Tehran depicting a crudely manipulated assemblage of prominent Iranian women outfitted in the mandatory hijab alongside the Islamic Republic of Iran’s favorite current slogan: “Women of Our Land.” 1 Within hours of the poster’s unveiling, calls for its removal from the public sphere by the women in the image and/or their allies began. Feminist novelist Simin Daneshvar called not just for its removal, but its burning; Parvaneh Kazemi, one of the only Iranian women who has climbed Mt. Everest, posted on Instagram that “the name and image of us women are only used [by the Islamic Republic of Iran] for abuse;” actor Fatemeh Motamed uploaded a video to multiple social media platforms stating “I am a mother of all children who were killed in this land, not a women in the land of murders [killers];” the screenwriter Alidata Mehotooni pointed out that one of the women depicted in the image, the photojournalist Nooshin Jafari, is currently serving a prison sentence in Evin Prison for “insulting state sanctities.” 2 By nightfall, the poster had disappeared—a reflection of what journalist Abbas Abdi observed on Twitter as the regime’s “contradictory and blocked sensibilities” to undermine and co-opt Iranian women’s struggles in the name of morality policing. 3

The diversity of generations, classes, and professional journeys of the women depicted in the poster gave me pause, not just as a reminder of the suppressive forces that Iranian people (women especially) endure and survive, but that representation, specifically that of the Iranian woman, continues to be the visual field upon which Iranian citizenship and personhood has been framed and contested—a contradiction, a blockage, impossible for theocracy and patriarchy to disentangle. Artist Taravat Talepesand’s current mid-career survey at Macalester College’s Law Warschaw Gallery points to this irrefutable fact, that the symbolic content of women’s bodies and representational histories mark that uneasy marriage between an Iran shaped by the will of Allah, the will of the Father, and the exuberant wills of the Iranian people.

Across the trajectory of the exhibition, Talepasand’s women undulate within their representational worlds with a power and presence denied to them by regimes past and present, from the commencement of the Pahlavi reign to the iconoclastic seizure of Iranian political and cultural life by Ayatollahs Khomeini and Khameini. Despite the encroaching patriarchal orders that lurk in the spaces beyond and outside the figure’s environs, whether painted with resplendent pigments mixed by hand or delicately sketched in graphite or hash oil, Talepasand’s women occupy a representational void in the current Iranian regime’s repressive aesthetic order. Reliant on a confusing mythology of advanced capitalist modernity and authoritative religious modesty, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s definition of femininity sits within a philosophical aporia that exclaims freedom from inside its own ideological prison. It is not Iranian women who have become hysterical, but the state and its keepers.

These silent screams of Iran’s women undulate inside and around Talepasand’s sensuously painted heroines. In Lioninoil II (2014), a young woman’s alert gaze rejects of calm plasticity of Classical bust sculptures in favor of the frightened and frenetic. With eyes, brows, and mouth raised in prophetic horror, her dark cloud of hair alive to present and future terror, the young beauty stands as a monument to all that young women experience, fear, and endure in patriarchal societies. As one of the earliest self-portraits in Talepasand’s oeuvre, the work points to the concerns of an artist acutely aware of the politicization of the Iranian female body—her own body—as a site of creative power and controversy, eliciting rage and redemption simultaneously.

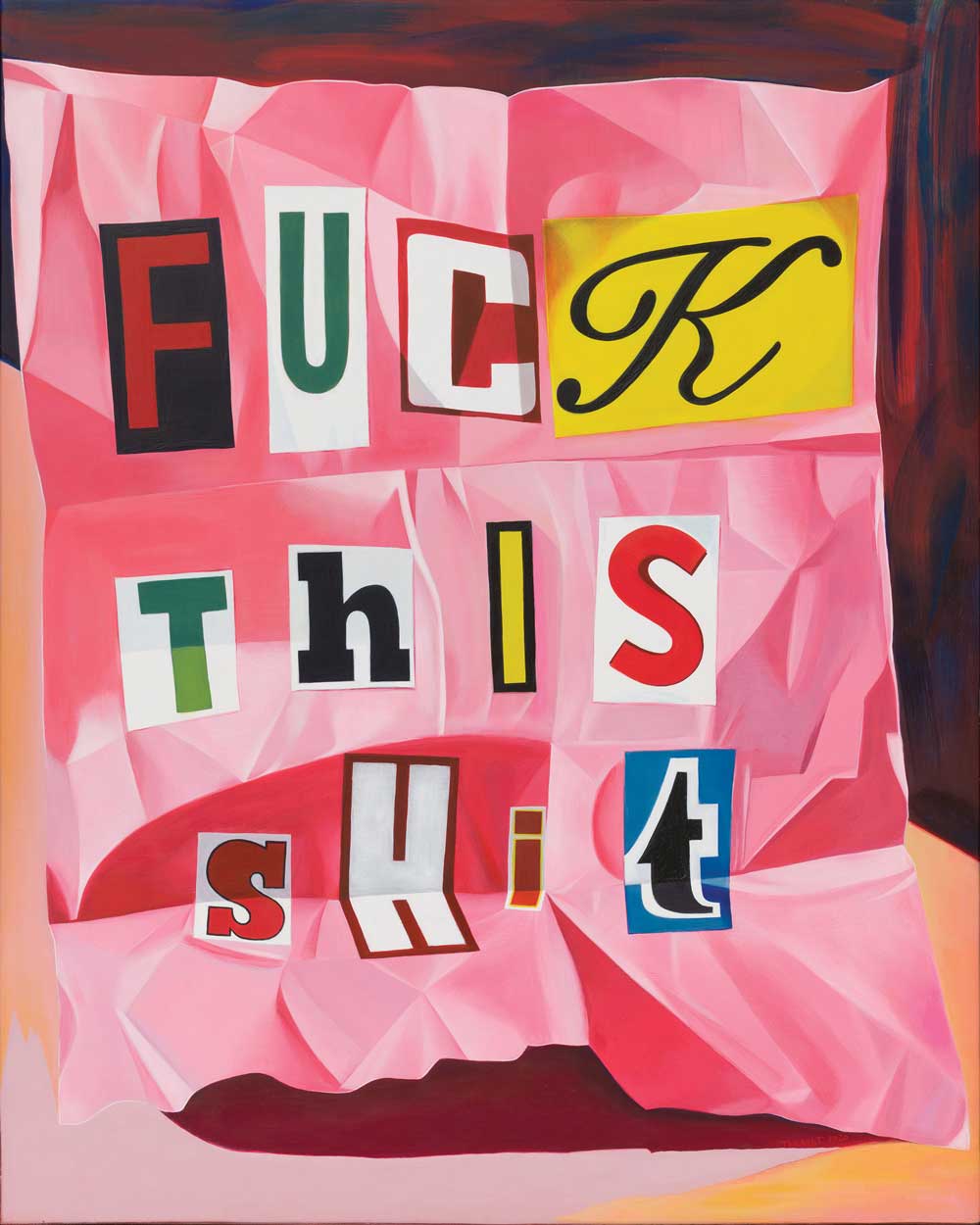

Talepasand’s materials and methods point to this gap. Acutely attuned to the viscous materiality of paint and its historical supremacy as a medium for elucidating state power and spiritual illumination in Eastern and Western cultures, Talepasand’s aesthetic gestures break the wave between affirmations of classical tradition and contemporary challenges to those hierarchies. Like many children of diaspora and exile, old plays with new, homelands tussle for supremacy, gestures and contexts become sampled and remixed anew. Thus, a painted ransom note exclaiming “FUCK THIS SHIT” (2021) oscillates easily between contexts, from a protest cry against the executions, imprisonment, and sexual violence of Iranian youths by the Islamic Republic to the fall of Roe v. Wade and the rise of Christian originalism on the Supreme Court in the United States, while a commissioned Iranian carpet scattered with a crude likeness of former President Donald Trump’s crying face signifies Talepasand’s rejection of both Iran’s religious, political, and cultural edicts against blasphemous figuration and the understanding of Persian carpetwork as “outside” contemporary art’s aesthetic and conceptual investments. Leaving behind the female body at times allows Talepasand to interrogate and draw forth the assumptions, individual actors, and situational relationships that shape a world of danger, oppression, and limitation for womxn across geographies and cultures. As Black feminist philosopher Audre Lorde reminds us, “Oppression against women is the our-context, our world’s—our lives’—eternal return.” 4

While the brutal crackdowns against Iranian protesters fighting with and on behalf of women and their fellow marginalized communities carry on across the country—in small villages in the north and cosmopolitan centers alike—many of us across the Iranian diaspora watch the snippets of violence, mourning, and rage on our social media feeds in horror, unable to shake the realization that we have seen all of this before and never seen any of this before, simultaneously. For those of us, like Talepasand and myself, who remain the daughters of the Green Movement of 2008/09, a recognition of the historical ties between today and the reformist movements that took hold of Iranian politics in the early 2000’s cannot be ignored or downplayed. While Khatami’s government was on the whole dismissive of women’s concerns, activists in Iran—hopeful for a path towards democratization—shaped a feminist movement grounded in the understanding that gender inequality was structurally entwined within clerical rule. Built on grassroot efforts, intersectional ethics, and an investment in communicating the pragmatic ways in which culture and law discriminated against women and queer people across many spheres, from inheritance and child custody to divorce and workplace protections, this new wave of Iranian feminism did not call for the regime’s downfall, but for new legislation that would protect women’s political and economic rights equitably. These calls were met with suppression and violence: leaders were imprisoned, interrogated, exiled, and disappeared; those who remained went underground or shifted their attention to smaller, less controversial issues such as sexual harassment on public transport. Yet, many of the protesters on the streets today are the daughters and sons of those original activists. While the current movement may not have a singular leader, it does indeed have a provenance. These historical precedents form the lake that Talepasand’s female figures swim within.

We must continue to make, build, create, paint, write, post, pray, share, shout and stomp for the Iranian people’s freedom, for intergenerational justice, for the dead scattered in the wake of this forty-year political storm, for the travesties that line the road to a future of something else. “It will not always be like this; it will never be like this again.” 5

Jîn. Jîyan. Azadî.

Zan. Zendegi. Azadi.

زن زندگی آزادی

Women. Life. Freedom.

–Dr. Jordan Amirkhani

New Orleans, LA

December 20, 2022

- See Tehran AFP, “Tehran billboard of famous women in hijab changed a day after going up,” France24.com, October 14, 2022. Link: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20221014-tehran-billboard-of-famous-women-in-hijab-changed-a-day-after-going-up

- See Azadeh Moaveni, “Diary: Two Weeks in Tehran,” in The London Review of Books, Vol. 44, No. 21, November 3, 2022. Link: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v44/n21/azadeh-moaveni/diary

- See the daily Twitter news updates concerning Iranian journalists, activists, artists, and human rights workers at the Center for Human Rights in Iran website. Link: https://iranhumanrights.org/2009/06/news/

- See Audre Lorde’s transcription “A Conversation between Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich,” republished in Your Silence Will Not Protect You: Essays, London: Silver Press, 2017, p. 49.

- One of many protest slogans exclaimed in the earliest days of the current Iranian uprising. See Miriam Berger, “What Iranian protest slogans tell us about the uprising,” in The Washington Post, October 21, 2022. Link: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/10/21/iran-protests-slogans-demands/